Executive summary

Congressional Republicans are expected to consider a Medicaid work requirement as part of upcoming reconciliation legislation (e.g., Sanger-Katz 2025; Hooper and Payne 2025). Proposals vary in who they apply to and what they direct enrollees to do, but they generally require adult enrollees to be employed (or engaged in another approved activity, like schooling) for some number of hours per month to remain eligible for Medicaid, subject to some exemptions.

To inform this pending debate, this paper examines one of the few precedents for such a policy: a work requirement implemented by the state of Arkansas under a waiver granted by the first Trump administration. Arkansas applied its policy for nine months, from June 2018 through February 2019, before being stopped by a court ruling. The Arkansas policy closely resembles the federal work requirement passed by the House of Representatives as part of the Limit, Save, Grow Act of 2023, a potential starting point for upcoming reconciliation legislation.

Prior research has shown that Arkansas’ policy reduced Medicaid enrollment and increased uninsurance among low-income adults in Arkansas (Sommers et al. 2019; 2020; Gangopadhyaya and Karpman 2025). This research also finds that the number of enrollees that the state deemed non-compliant with the requirement far exceeded the number of enrollees who neither qualified for an exemption nor were engaged in the required activities, indicating that most enrollees lost coverage due to challenges in reporting information to the state, not true non-compliance with the policy. Meanwhile, this research finds no evidence that the Arkansas requirement increased employment among the population subject to the policy, contrary to proponents’ hopes.

Because the Arkansas policy was in effect for a short time—and, indeed, was still phasing in when it was stopped in court—it is not straightforward to use the Arkansas experience to assess how this policy would have affected Medicaid enrollment over the long run. To overcome this obstacle, this paper develops a dynamic structural model suitable for using the Arkansas experience to forecast the long-run enrollment effects of the Arkansas policy and similar policies.

My main findings are as follows:

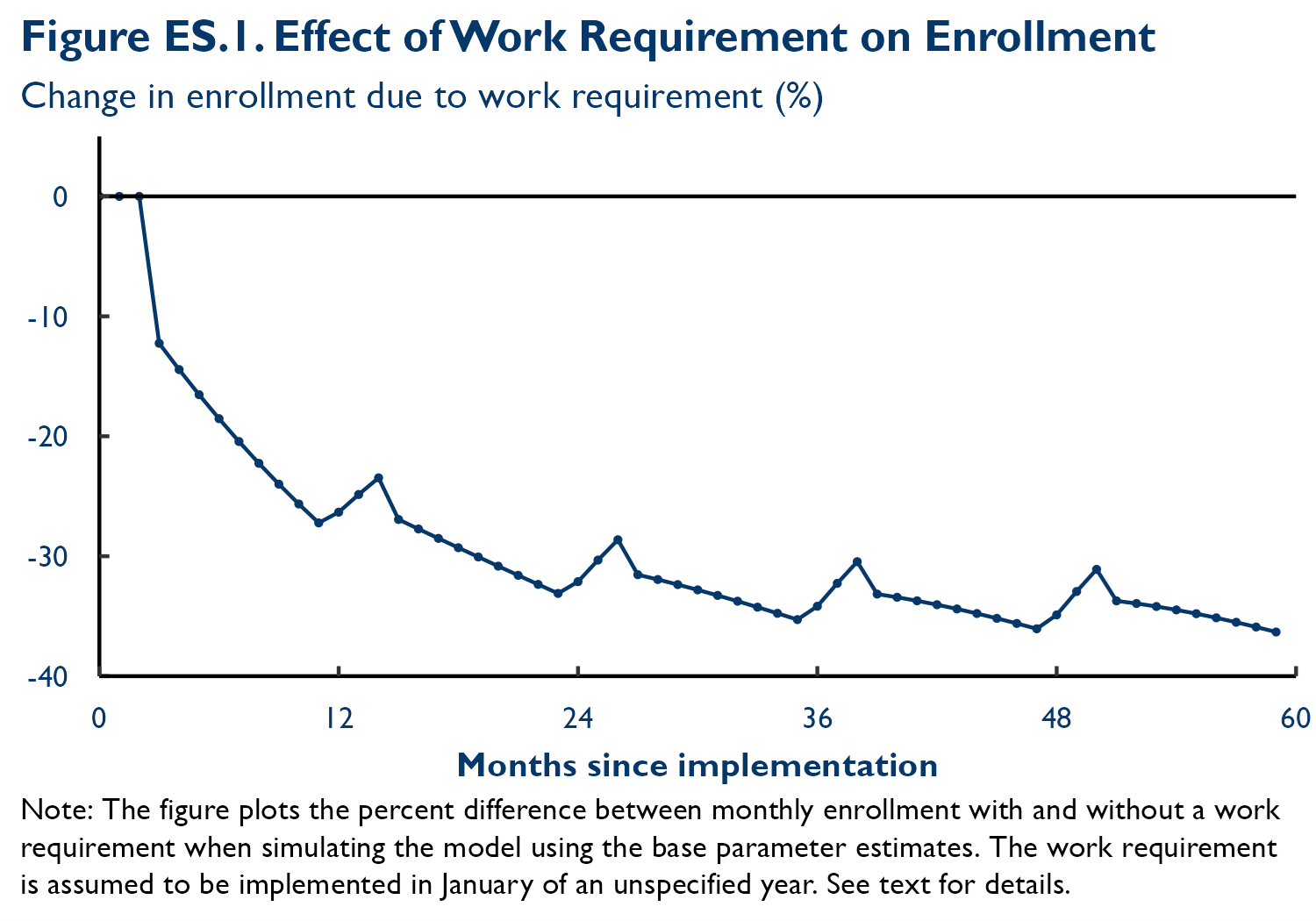

- A work requirement like Arkansas’ would reduce Medicaid enrollment by an estimated 27% at the end of the policy’s first year and by 34%, on average, over the long run. Figure ES.1 plots how the simulated effect on enrollment evolves over time. Enrollment declines grow over time because, as time passes, more enrollees experience temporary spells of non-compliance that cause them to lose coverage and because removed enrollees are slow to reenroll once eligible to do so.

- If outcomes under the 2023 House policy mirrored my estimates for Arkansas’ policy, Medicaid enrollment would fall by around 4.5 million people nationwide in the long run. Because of the close resemblance between the Arkansas policy and the 2023 House policy, my estimates offer a good starting point for assessing the impacts of this prospective federal policy. This 4.5 million estimate assumes that the policy would apply to people enrolled under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) Medicaid expansion who fall in the 19 to 55 age range specified in the House bill; it was obtained by multiplying my estimate of a 34% long-run enrollment reduction and the Karpman, Haley, and Kenney (2025a) estimate that there will be 13.3 million Medicaid enrollees in this group in 2026.

- States might implement an Arkansas-like policy differently than Arkansas did, which could lead to larger or smaller enrollment declines. States might operationalize a work requirement differently due to differences in their administrative capacity or policy goals. It is unclear whether this would lead to larger or smaller enrollment declines. When Karpman, Haley, and Kenney (2025a) analyze data from New Hampshire (which paused its work requirement before beginning disenrollments) alongside data from Arkansas, they find that the New Hampshire data point to somewhat larger enrollment declines. By contrast, data from Michigan (which also paused a Medicaid work requirement shortly before beginning disenrollments) suggest somewhat smaller declines, although this could partly reflect differences in the design of Michigan’s policy. In addition, other evidence suggests that Arkansas’ administrative capacity was neither especially strong nor weak (Brooks, Roygardner, and Artiga 2019; Brooks et al. 2023; 2025).

As the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) emphasized in its analysis of the 2023 House policy, some states might elect to use state funds to cover enrollees who were no longer eligible for federal funding under a federal requirement (CBO 2023). If many states did so, this could substantially reduce enrollment declines, albeit at a large state cost. While predicting state decisions is beyond the scope of this analysis, there is reason to doubt that this would be the typical outcome. Before creation of the ACA Medicaid expansion option, relatively few states covered adults without children (the group at risk of disenrollment under the 2023 House policy), and when they did so, they often received at least some federal support (Heberlein et al. 2011), which would not be the case here.

- Changes in macroeconomic conditions or differences in enrollee mix between Arkansas and other states could also affect enrollment outcomes. Many forecasters believe that the national economy will weaken in the coming months (e.g., Santilli and DeBarros 2025). A weaker economy would likely increase Medicaid enrollment, especially among the expansion population, increasing the number of people subject to a work requirement (Jacobs, Hill, and Abdus 2017). It would likely also push the unemployment rate above where it was in Arkansas while its policy was in effect. During those months, Arkansas’ unemployment rate was 3.7% or lower, lower than the national unemployment rate was in 89% of months since the year 2000. Lower employment might increase the rate at which enrollees subject to a work requirement lose coverage, perhaps most importantly by reducing the number of enrollees for whom states could use existing data on enrollee income to automatically ascertain whether enrollees are in compliance with the policy. On the other hand, there is some evidence that the Arkansas Medicaid enrollees are employed at lower rates independent of the state of the business cycle (Garfield, Rudowitz, and Damico 2018; Tolbert et al. 2025), which could operate in the other direction.

- Work requirement policies designed differently from Arkansas’ could cause larger or smaller enrollment declines. For example, a policy that removed enrollees from Medicaid after one month of non-compliance, rather than after three months as under the Arkansas policy and the 2023 House policy, would lead to larger enrollment declines, while changes in the opposite direction would lead to smaller declines. Other changes—including changes to which enrollees are subject to the policy, to the list of available exemptions, to the activities enrollees are required to engage in, to how states ascertain compliance with the policy, or to how long removed enrollees must wait before returning to the program—could also result in markedly different enrollment effects.

- My estimates are subject to meaningful uncertainty, but a suite of sensitivity analyses all find enrollment declines of between 23% and 43% over the long run. The data also offer some hints that my base estimates overstate how quickly enrollees removed from the program for non-compliance would reenroll once eligible to do so, which suggests that outcomes may be more likely to fall in the upper part of this range than the lower part. The main source of uncertainty in my estimates is that developing a model suitable for estimating long-run enrollment effects requires making some strong assumptions.

- My estimates are similar to Karpman, Haley, and Kenney’s recent estimates of the effects of the 2023 House bill, but much larger than CBO’s estimate for that bill. When using data from Arkansas, Karpman, Haley, and Kenney (2025a) project that a work requirement similar to the 2023 House bill would cause 34% of those subject to the policy to lose eligibility for federal funding; this rises to 39% when using data from New Hampshire. These estimates are very similar to my estimates despite substantial differences in our analytic methods. By contrast, CBO’s analysis of the 2023 House bill concluded that only 10% of those subject to the policy would lose eligibility (CBO 2023). It is unclear how CBO arrived at its estimate. However, taken together, my estimate and the Karpman, Haley, and Kenney estimate suggest that the CBO estimate may be too small.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The author thanks Aviva Aron-Dine, Tom Buchmueller, Richard Frank, Michael Karpman, Jenny Kenney, Jeanne Lambrew, Christen Linke Young, and Gideon Lukens for helpful comments on a draft of this analysis. He thanks several members of the staff of the Brookings Institution for their outstanding contributions to this project: Ben Graham and Paris Rich Bingham (research assistance), Rasa Siniakovas (editorial and web posting assistance), and Chris Miller (formatting assistance). All errors are the author’s own.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).