When American propagandists beamed broadcasts beyond the Iron Curtain during the height of the Cold War, the message was in part exactly what you’d expect. “Keep up your hope,” an announcer said in Czech in one such broadcast. “For the Communists will be driven from our homeland and freedom will yet prevail.”

But the program also included lighter material: Listeners were treated to music banned across much of the Soviet Union, such as jazz or local folk songs, followed by a news broadcast.

Funded by the U.S. government, Radio Free Europe and its sister station Radio Liberty used a tactic called pre-propaganda, which refers to propaganda not directly related to the political message of the propagandist. It lays the groundwork for more overt propaganda through audience-building and myth-making—in this case, using jazz as an on-ramp to sell the American way of life.

More recently, the tactic has been adopted by Russia in its efforts to meddle in American politics. By pushing stories from a diverse body of outlets and posting material on different platforms, Kremlin propagandists adapted the concept of pre-propaganda in their efforts to interfere in the 2016 election, according to a recent study by researchers at the Center for Social Media and Politics at New York University, which harvests social media data to study political attitudes and behavior online.The study’s findings show how states are adapting classic propaganda tactics to social media, and why policymakers must consider how information spreads across platforms to protect voters from these covert campaigns.

The study—by Yevgeniy Golovchenko, Cody Buntain, Gregory Eady, Megan A. Brown, and Joshua A. Tucker—investigated the online propaganda strategies of the Internet Research Agency (IRA), a Kremlin-linked “troll farm.” The U.S. Department of Justice accused the group of spreading disinformation online to interfere in the 2016 election, indicting 13 Russians it said were involved in the scheme before ultimately dropping the case.

The IRA’s operations have kicked up a debate among policymakers and analysts over Russia’s aims: Did the Kremlin try to help Donald Trump’s campaign and hurt Hillary Clinton’s? Or did it support both liberals and conservatives at the same time to inflame partisan tensions rather than boosting one candidate over the other?

Analysis of more than 1,000 IRA-operated Twitter accounts found evidence to support both claims, but indicated that overall the IRA was interested in helping the Trump campaign.

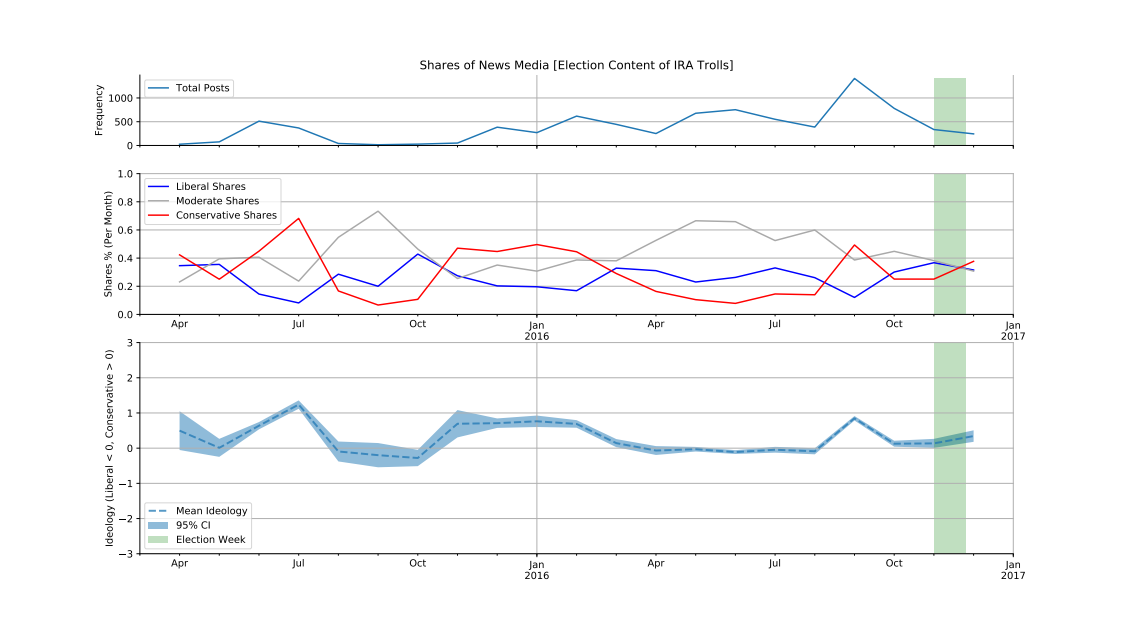

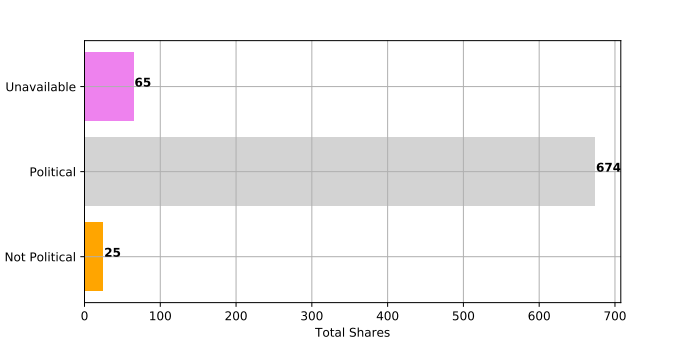

The research focused on tweets by IRA trolls (accounts controlled by humans who masked their identities) about the 2016 election containing hyperlinks to political news stories, YouTube videos, and other content. More than 30 percent of the politics-related IRA tweets examined linked to external websites. Of these, about 10 percent linked to news stories, and 3 percent linked to YouTube videos. Trolls linked to conservative news sources (34 percent) more often than to liberal ones (24 percent) and skewed conservative in their sharing patterns over time.

This finding supports the first theory—that the IRA tried to support the Trump campaign—and indicates that the IRA exploited social media platforms’ interconnected ecosystem of links, shares, and likes to spread disinformation.

But the IRA didn’t just spread fake or hyperpartisan news; it also drew content from a wide range of news sources across the ideological spectrum. About 42 percent of links amplified news stories from moderate sources. And the trolls shared news from reputable, mainstream sources, such as The Hill and The Washington Post, not just from biased or discredited sources, such as the far-right Breitbart News.

In sharing liberal and conservative stories alike, Russia tried to sow discord by playing both sides. It’s also possible that Russia was simultaneously trying to build an audience among moderates before luring them to the Republican side. Indeed, it may have been doing both at the same time.

Note the researchers examined the news domains, or sources, shared by the trolls. The analysis didn’t include news content, which means it’s possible that stories from liberal sources contained anti-Clinton messages—such as the controversy over her emails.

YouTube appears to have been a crucial part of the IRA’s cross-platform strategy. The trolls linked to the video-sharing platform more often than to most other external websites, sharing overwhelmingly conservative content (75 percent). And while the trolls cast a wide net when sharing news stories, they tightened their focus to a selection of mostly pro-Trump, pro-Republican YouTube videos.

Finally, the researchers tested for ideological consistency in troll behavior over time. That is, did the conservative trolls remain conservative, and the liberal trolls remain liberal, throughout the 2016 campaign? For the most part, the answer is yes. But here’s where it gets interesting: Trolls who mostly shared liberal news stories were more likely to cross ideological lines by also sharing conservative YouTube videos. Trolls who mostly shared conservative YouTube videos, on the other hand, rarely shared liberal ones.

This behavior points to the IRA’s use of pre-propaganda. The IRA may have shared news stories from diverse sources to build credibility and a broad audience, before dosing liberal and moderate users with conservative YouTube content. A propaganda campaign can target liberals, moderates, and conservatives, with an overall goal of helping the Republican campaign. The sheer amount of conservative content in the dataset suggests this was the case, though the IRA may have planned for Trump’s defeat by including liberals and moderates in their audience.

The researchers coined a term to describe what they found: cross-platform pre-propaganda, or pre-propaganda that exploits the interconnected nature of platforms. By using Twitter to get users onto YouTube, the IRA deployed a tactic that represented a degree of historical continuity in state-driven propaganda, and took advantage of social media as a means to lower costs, increase scale, and maintain the anonymity of covert campaigns.

When it comes to state propaganda, the major platforms don’t exist in a vacuum. Together, they provide a whole ecosystem for malicious actors to exploit.

Venuri Siriwardane is a researcher and editor at the Center for Social Media and Politics at NYU.

Twitter and Google, the parent company of YouTube, provides financial support to the Brookings Institution, a nonprofit organization devoted to rigorous, independent, in-depth public policy research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Russian trolls are adapting Cold War propaganda techniques

May 15, 2020