Most colleges charge students more than they can afford. Statements to that effect are typically based on a misplaced focus on the “sticker price” of college. That price (formally labeled the cost of attendance) includes the full amount of tuition and fees, living expenses, and other related expenses. The average sticker price adjusted for inflation has nearly tripled in the last four decades.

Yet most students will pay less than the sticker price. They receive financial aid from the government and/or the institution they attend that reduces the amount they really pay.

But it is not enough. Lower- and middle-income families in particular are asked to pay “net prices,” which factor in financial aid, that are beyond their means.

Every student deserves the opportunity to obtain an affordable, high-quality college education. College can raise lifetime wages and expand students’ understanding of the world. Our society also benefits if a high-quality college education is available to all students. A college education promotes social mobility, civic engagement, and worker productivity, among other things. But if some students are unable to take advantage of this opportunity because it is unaffordable, we all lose those benefits.

How do we satisfy the dual, and conflicting, goals of improving access while maintaining quality?

But college affordability does not occur in a vacuum. If students pay less, institutions’ revenue falls. Colleges will have less money to maintain the quality of our higher education system if we improve access by lowering costs. How do we satisfy the dual, and conflicting, goals of improving access while maintaining quality?

My goal in this report is to evaluate the pricing systems in different types of higher education institutions, focusing on whether they accomplish these two conflicting goals. How could those systems be modified to increase access and maintain quality?

Ultimately, I argue that our higher education system cannot accomplish these dual goals without additional governmental resources devoted to the system. Highly-endowed private institutions largely already satisfy them because they have extensive financial resources, but their model is difficult to replicate. Public institutions simply need more funding to provide affordable pricing to all students while maintaining educational quality. The solution for less well-endowed private institutions is unclear. Greater government support will come with further challenges: larger subsidies for colleges and universities will also require additional regulations to maintain quality while avoiding excessive spending. And any solution to the affordability issues that colleges face requires far greater transparency in college pricing.

Readers looking for specific numbers regarding who should pay how much or for specific policy proposals will be disappointed—this is a conceptual exercise. But these concepts have important implications for higher education and the policies that affect its operation.

How much should students and their families be asked to pay?

Consider students from low-income families (perhaps below the poverty line or twice the poverty line, corresponding to about $30,000 to $60,000 for a family of four). Their families’ income may have fluctuated during their lives, but they have probably had moderate income throughout their childhood. They likely have little or no wealth. Their focus is putting food on the table and a roof over their heads. There is little left over to pay for college.

These students really cannot afford to pay anything out-of-pocket to attend college. They might be asked to pay a low net price that could be covered by a reasonable level of student loans and work-study earnings. But many students are averse to high levels of debt and working extended hours is inconsistent with a quality education. These forms of payment should not be excessive to promote attendance and graduation. For simplicity, I focus the analysis here on what students are asked to pay out-of-pocket, which should be zero for the lowest-income students.

Students from very high-income families have the financial resources to pay a lot for college. They likely have substantial wealth. Considering the high cost of delivering higher education, the large economic returns, and the value of the personal experience of attending college, these students from high-income families should pay a substantial amount for college.

But they should not pay an excessive amount. Some limit on the price that these students pay is warranted. Most colleges and universities are organized as nonprofit institutions with a social mission. Charging exorbitant prices to any student, even very wealthy ones, would violate those principles.

One reasonable candidate for the maximum price is the institution’s average expenditure per student. Determining the exact value of that statistic may be complicated by the variety of activities that colleges and universities engage in (research, athletics, medical centers, and the like). The point of this exercise is not to specifically define how to construct it, but to recognize that such a concept exists and is relevant in setting college prices.

Note that this proposed maximum price is not the same as the “sticker price” (formally labeled the “cost of attendance,” or COA). Some institutions offer some form of financial aid (need-based and/or merit-based awards to most of their students (as described below). Their sticker price exceeds the true maximum price that most/all students pay. And highly endowed institutions often subsidize even their highest-income students; the sticker price is less than average expenditure per student. Setting the maximum price at the average expenditure per student does not require that anyone be charged that price; it allows institutions to charge less than that amount should they so choose.

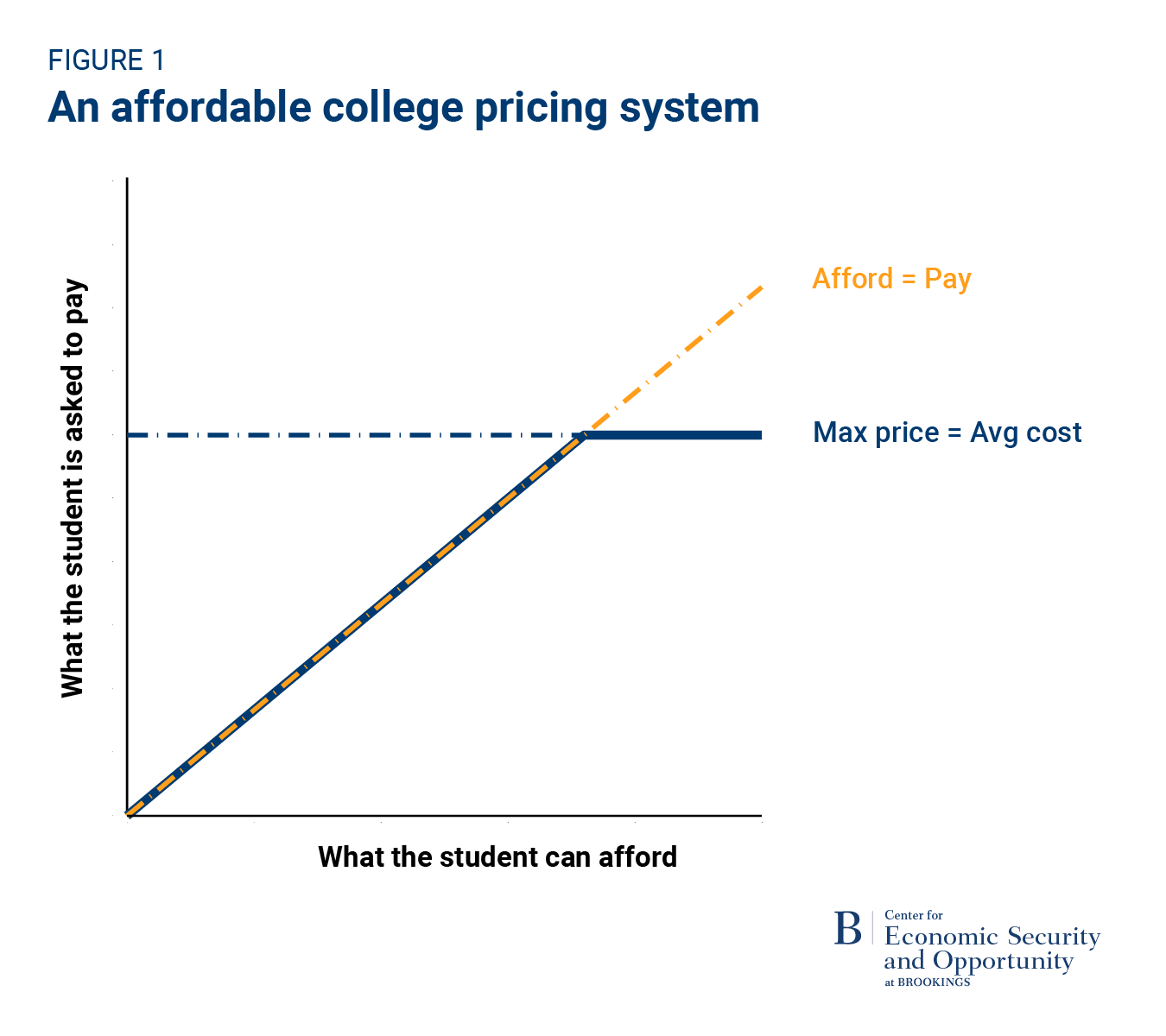

So far, I have argued that the price for students from low-income families should be zero, and for high-income students the price should be no more than the institution’s average expenditure per student. Students with incomes between these two extremes should pay a price somewhere in between these two values. Families that can afford to pay more should pay more. This is characterized in Figure 1.

A system like this one requires two important pieces of information. The conceptually easy one is the institution’s average expenditure per student. The harder one is determining how much each family can afford to pay based on their finances. This involves value judgements about what is reasonable for families to afford to pay, but that is what the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) and the College Scholarship Service (CSS) Profile do now. Whether these systems precisely capture how much a family can afford to pay is unclear, but one could imagine it is possible to accomplish that goal.

College pricing does not work the same as pricing in a typical market. For most products, everyone pays the same price, determined in the market without regard for what specific consumers are willing or able to pay. If you cannot afford it, you do not buy it.

But such an approach to pricing is not well-suited for higher education. Unlike for most “goods,” “firms” (colleges) can and do charge “consumers” (students) different prices. Most students attend nonprofit institutions, for which maximizing profits is not the main objective. At public institutions, the state government is also involved in determining the prices colleges charge to different students. The basic model of pricing in competitive markets does not apply here. The pricing system I propose for higher education is specifically designed to ensure that everyone can afford to attend college.

How should this system be financed?

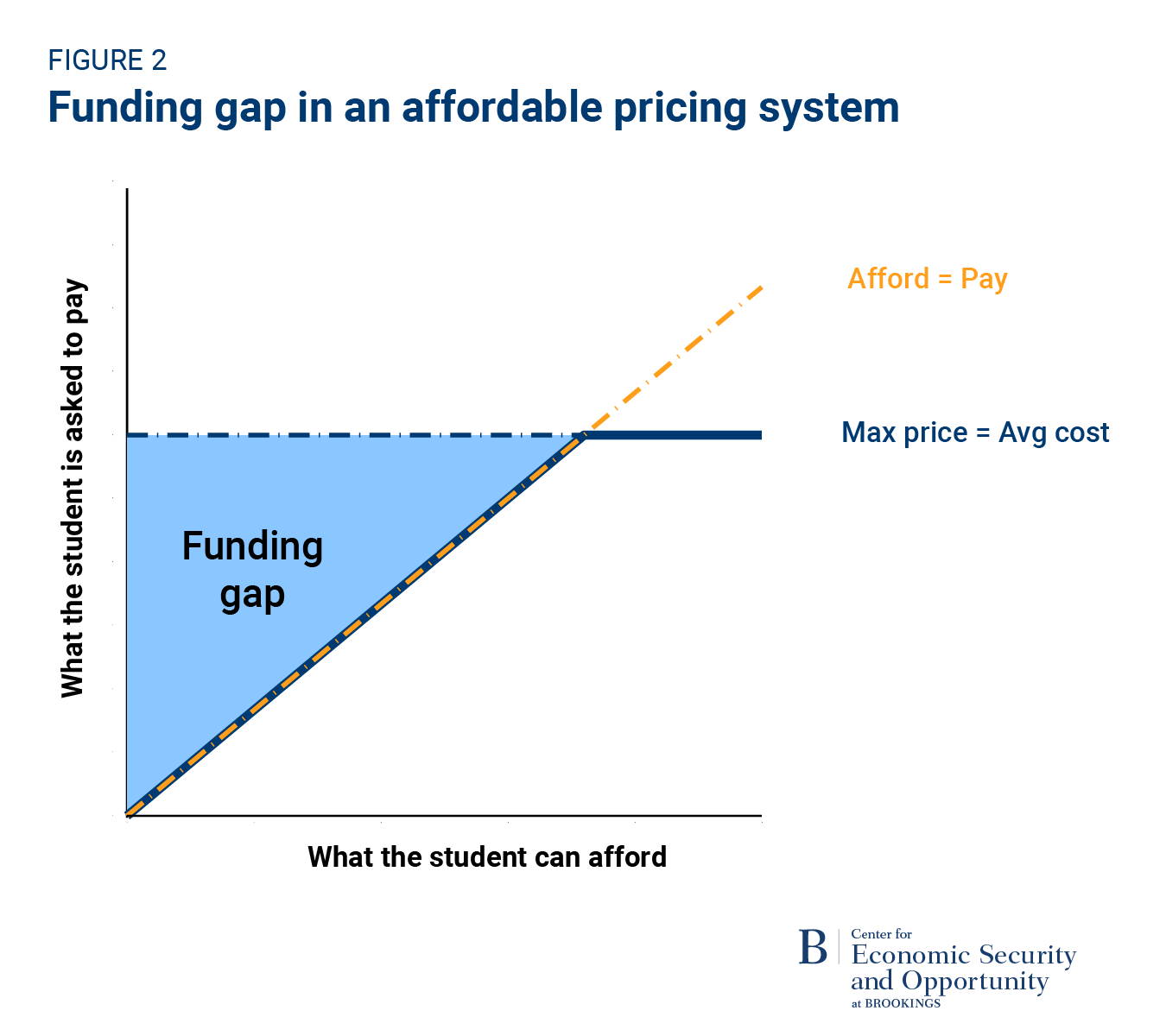

One obvious problem with this system is that revenue from students is insufficient to cover the cost of operating higher education institutions. This is demonstrated in Figure 2. Students from higher income families would pay no more than the institution’s average expenditure per student. Everyone else would pay less than that. Such a system will always generate less revenue for an institution than it is spending. Additional funding is required to cover its costs.1

There are two main sources of funding available to cover those costs: endowments and public funding. Many institutions, including some public colleges, have endowment funds provided by past donors. A relatively small number of largely private institutions have very large endowments. The returns from these funds are used to cover the cost for those students who pay less than the average cost.

Public funds collected through the tax system could also be used to fill in this gap. They could come from the federal or state governments. Because most taxes are progressive, higher-income taxpayers provide funds that enable lower-income students to attend college.

For those institutions that require public funding to cover their funding gaps, this financing system would create incentives to spend more money. If an institution spends more, the size of the funding gap increases. But if public funds automatically cover the gap between average spending and what students can afford to pay, the institution could “afford” those spending increases. Some have worried that the current Pell Grant program similarly provides incentives for excessive institutional spending. This incentive would be much greater if the government guaranteed it would completely fill in this funding gap.

Some form of regulation on institutional spending would be required to manage this incentive. Such regulations would surely be complicated and require extensive discussion. Below, I discuss the types of institutions where these regulations may be warranted.

Ensuring that institutions can spend enough to provide a quality education is a key consideration in designing such a system. Reining in spending is necessary, but maintaining the strength of American higher education remains a priority. Regulations designed to limit excessive spending still need to incorporate the need for sufficient spending to maintain students’ educational attainment.

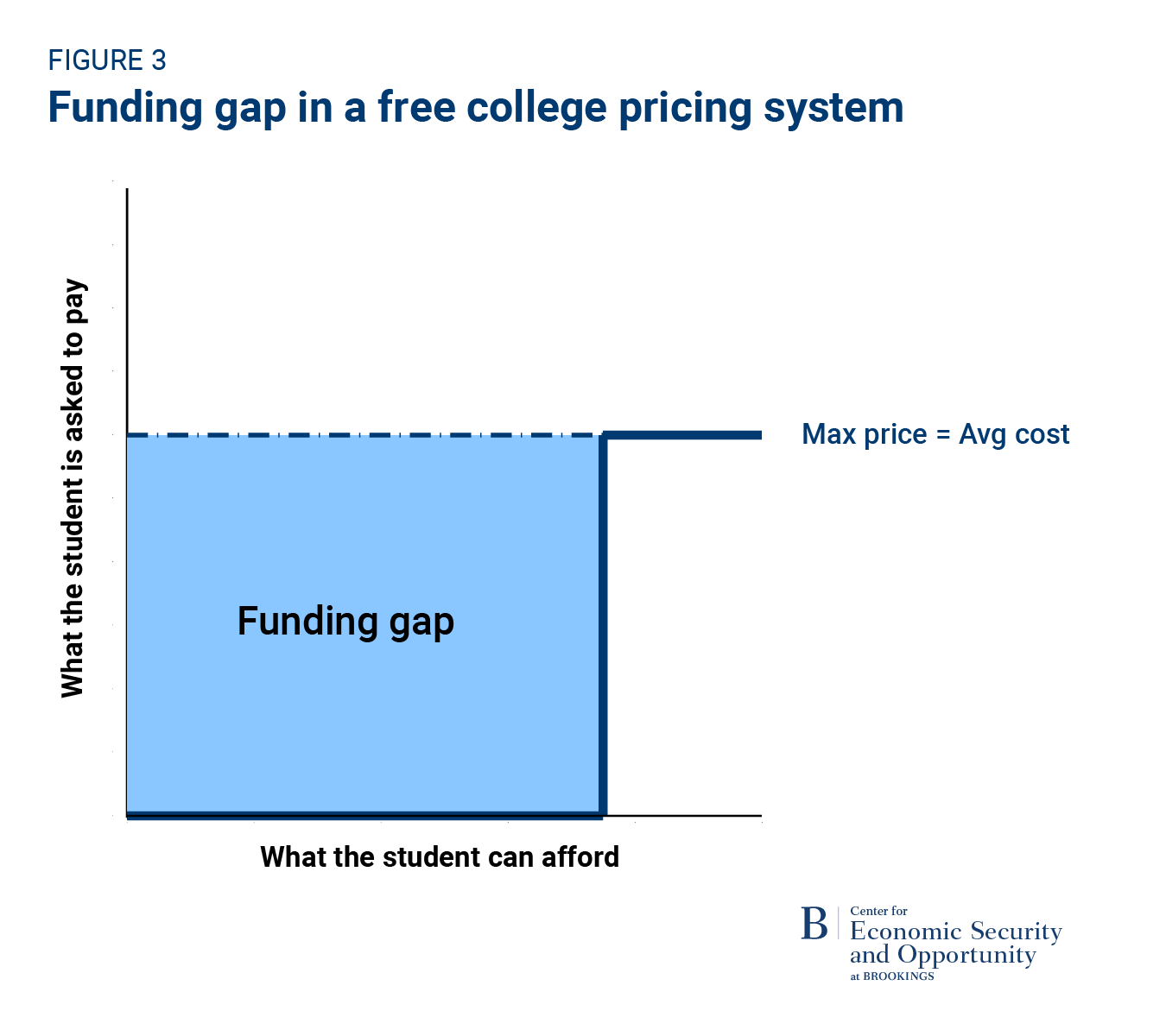

The framework presented in Figure 2 also can be modified to represent a “free college” system or the college pricing approaches used in many European countries. In extreme versions of both types of systems, the student would not be expected to pay anything regardless of family income. In practice, such systems often focus just on tuition and fees. To satisfy affordability goals, such a system would also need to include these costs along with living and other expenses.

Suppose we imposed an income cap, such that families who can afford to pay a lot receive no subsidy (they would pay a price equal to per-pupil spending).2 The funding gap triangle illustrated in Figure 2 would convert to a funding gap rectangle, as displayed in Figure 3. For every student below the income cap, students would pay nothing. The government would have to provide all the necessary funds to cover their educational expenses.

If there were no income cap —that is, all students receive the same subsidy, regardless of income— then none of an institution’s revenue would come from students. There would be no need for prices, so there would be no need to regulate them. De facto, an institution’s spending per student would be set by the amount of the subsidy provided by the government. Again, that level of spending would need to be set appropriately to support a high-quality college education without being excessive.

The level of government funding required for such a system is much larger than what would be needed for the system shown in Figure 2. Such a high level of funding could be politically difficult to achieve in the United States.

How much do students actually pay for college?

Higher education institutions receive public subsidies already in the form of Pell grants, subsidized student loans, and state payments to public universities. They also use their own funds to provide additional financial aid. Yet a college education remains unaffordable for many.

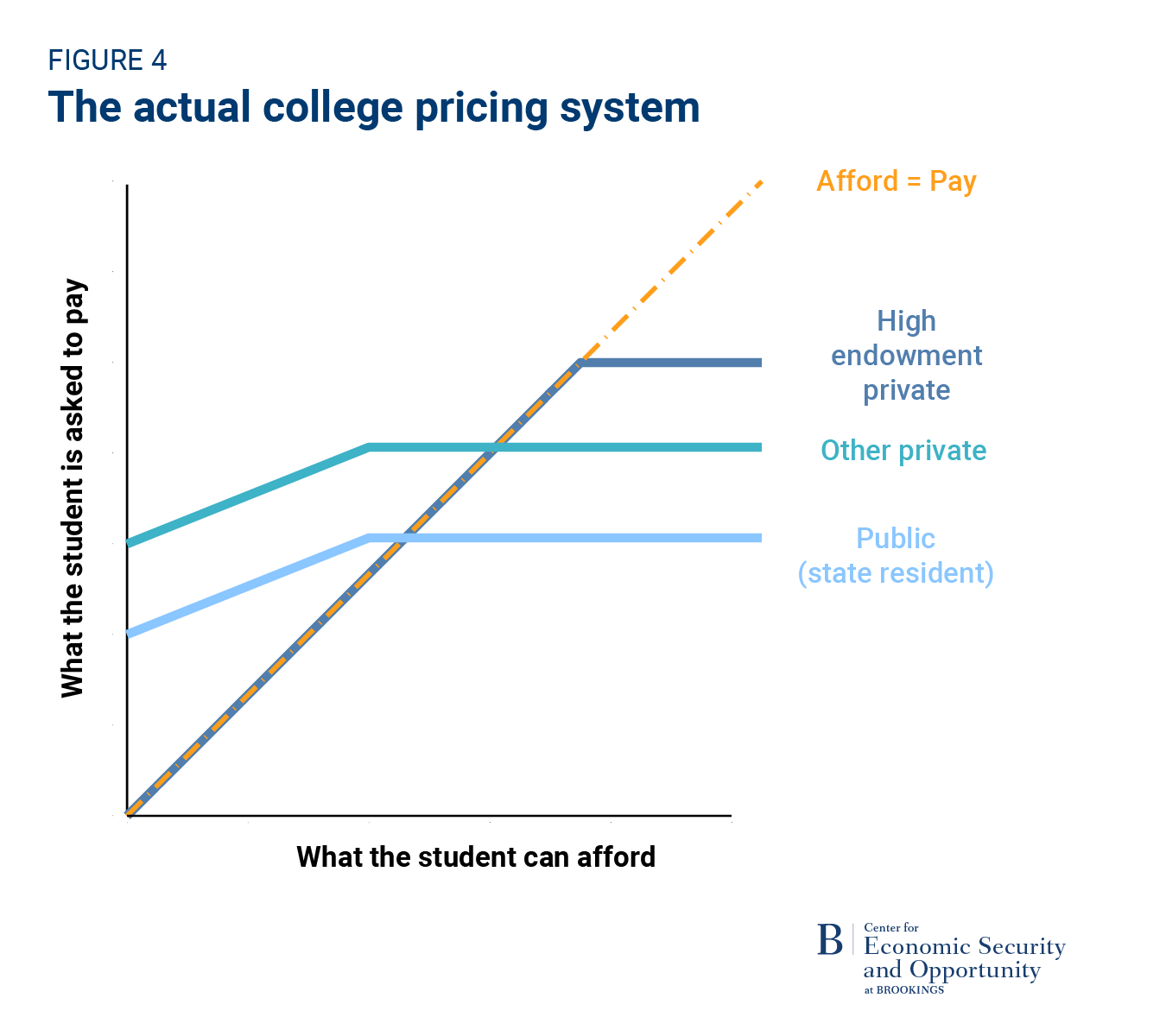

In past work, I have investigated how much students at different levels of income and assets pay at different types of institutions. That analysis focused on dependent students living away from their parents attending public and private 4-year institutions. I consider three types of institutions: private institutions with very large endowments, other private institutions, and public institutions with a focus on state residents.

Figure 4 displays a stylized version of the relationship between what students can afford and what they pay at different types of institutions. The 45° line (labelled “pay = afford”) represents payments that families can afford. Any price above that line is not affordable.

These patterns do not match public perceptions of college costs. Those perceptions generally focus on the sticker price, represented by the maximum price paid at each type of institution in this figure (the flat portion of each line on the right). Most students pay less than that amount because of financial aid.

Although many families pay less than the sticker price, lower- and middle-income students often must pay more than they can afford. Private institutions with very large endowments are the exception; no student pays more than they can afford (according to the financial aid formula they use). The reasons for these patterns differ by type of institution.

Large endowment private colleges and universities

At private colleges with large endowments, lower-income families face limited costs after factoring in financial aid. As family financial resources rise, the price rises. At some high-level of family income, students pay the high sticker price. This pattern is consistent with the affordable pricing system I described earlier.

These institutions can implement this type of pricing system because they have considerable market power and very large endowments. Their market power derives from their prestige and quality, which in turn derive from high levels of spending supported by their large endowments. This ensures that students from high-income families are willing to pay high sticker prices even if there are less expensive alternatives available (such as public colleges with lower sticker prices for state residents). These private colleges typically spend more per student than the sticker price. Even the high-income students are subsidized. Lower-income students require even larger subsidies. These institutions depend on returns from their very large endowments to fill the gap between their total costs and what students are able to pay.

These institutions are said to “meet full need,” meaning they charge admitted students the amount that the formula says they can afford. However, they may choose not to admit students with financial need. Institutions that are “need blind” do not consider need when they make admissions decisions and provide this high level of financial support for any student who enrolls. I will return to this distinction below.

Public colleges and universities

The defining feature of the pricing system at public institutions is a sticker price that is set by the state with a goal of maintaining affordability for state residents. It is typically tens of thousands of dollars less than the sticker price at private institutions. Students from higher-income families pay that price. The lower sticker price means less revenue for the institution, so spending per student at public institutions is typically lower than at large endowment private colleges and universities.

But many students cannot afford the sticker price at their state institutions. These institutions rarely have large endowments available to fund financial aid sufficient to fill the gap. Instead, their main additional source of funding is the state. But that funding is often insufficient to meet the needs of all students. A handful of flagships meet full need, but most public institutions do not. Lower- and middle-income students are often asked to pay more than they can afford at these institutions.

Other private colleges and universities

Private colleges and universities that do not have large endowments typically spend less per student and are more comparable in quality to public institutions. They compete much more directly with those colleges. That limits the price that higher income students are willing to pay to attend. Some students may be willing to pay more for attributes like smaller classes, higher graduation rates, and attractive campuses, but that premium is unlikely to be large, limiting the maximum price these private universities can charge.

The maximum price students pay is often less than the sticker price at these institutions. They set a high sticker price and then offer financial aid to most or all students. Students ineligible for need-based aid receive merit awards. For students eligible for need-based financial aid, any merit aid they receive is often offset by a reduction in need-based aid, so their net price is unaffected by merit aid. This is a marketing strategy designed to signal the quality of the institution (by setting a high sticker price) and to convey to students that they are valued (by offering “merit aid”). The students who benefit the most from these merit awards are those who do not require need-based financial aid and would otherwise pay the full sticker price.

These institutions, like many public institutions, may also provide additional merit aid targeted to the highest-achieving applicants. Again, these awards typically displace need-based grants and largely do not benefit students from lower- and middle-income families.

Overall, these private institutions struggle to provide adequate financial aid. They do not have large endowments or state support to fully finance the necessary subsidies. They simply do not have sufficient resources available to provide affordable college pricing for lower- and middle-income students.

What is the impact on college access?

Students for whom financial aid does not make the price of college affordable have limited options. They can borrow more, attend local institutions (community colleges or nearby four-year colleges) that may not match their academic abilities but reduce their living expenses, or perhaps not go to college at all.

High-need students may be directly shut out from admission to selective institutions as well. To help close funding gaps, those institutions may favor enrolling students who can afford to pay more. For instance, public institutions frequently enroll students who reside in other states. Those students pay much more than in-state students and may not be eligible for much financial aid. Similar practices are used at both public and private institutions in their enrollment of international students. Institutions may want to enroll out-of-state and international students because they offer a diversity of viewpoints that has educational benefits, but they also improve institutional finances.

Even many wealthy private institutions with very large, but not the largest, endowments face this problem. They do not have quite enough resources to support any student they wish to admit without regard to need. These institutions therefore limit how many students from lower- and middle-income families they admit. They meet full need for all enrolled students, but they are not need blind.

Such strategies are inconsistent with the goals of an affordable pricing system. Institutions’ use of these strategies to balance their expenditures with their tuition revenue highlights the crucial role of outside resources in making college affordable. The money to fill the gap shown in Figure 2 has to come from somewhere.

Can college pricing be fixed?

Our current system of college pricing leaves college unaffordable for many students. College costs more to provide than most families can afford to pay, and most institutions cannot make up the difference on their own. The ultimate problem is a lack of resources. Institutions need sufficient funding to enroll lower- and moderate-income students at an affordable price, a position only the wealthiest private institutions find themselves in. Most institutions simply need more money.

Where would that money come from? Larger endowments would help, but the donations needed and the time required for those funds to grow make such a solution impractical in most cases. Higher sticker prices paid by higher-income families could be used to generate surplus revenue, but that approach is unlikely to be well-received. Those students may demand more programs and services to justify those higher costs, driving expenditures up and eliminating some or all of the surplus. Greater direct support from state governments to public institutions would also help. Yet the politics of college affordability at the state level often involves keeping the sticker price low, even if that means cutting financial aid.

The federal government is the best funding source for the subsidies necessary to make higher education affordable. The federal government already subsidizes many activities that enable families to acquire basic life needs like food, housing, and medical care. Enabling students to obtain a college education regardless of their families’ finances has benefits that extend beyond the student receiving the education. We should provide the necessary subsidies to enable low- and moderate-income students to pursue higher education.

This is the approach I described earlier regarding ways to fill in the funding gap shown in Figure 2. In essence, this approach would lead to a pricing system where students’ full financial need is met, and admissions’ decisions are made in a need-blind manner. This would make college affordable, but automatically offering federal subsidies to fill the gap between average spending and student payments creates an incentive for institutions to spend more. Regulation on spending would be required to overcome this problem.

A remaining question is what institutions would be incorporated into this pricing system. It would be natural to include all public institutions in such a system. The government is already heavily involved in this sector, but funding is insufficient. The pricing system I described would alleviate the funding gap with regulations instituted to manage incentives for excessive spending.

Highly endowed private institutions would not need to be part of such a system because they largely use their own funds to cover the gap between spending and affordable student payments. It is ironic that these institutions attract considerable attention for their high sticker prices because they best satisfy the goals of an affordable pricing system. They also enroll a high percentage of high-income students who pay full price. Those students tend to have stronger academic credentials and are more likely to be admitted even holding constant academic credentials. The pricing system these highly endowed institutions use is virtually impossible for most institutions to emulate. They simply do not have the money.

But what about prices at private institutions with considerably smaller endowments? They do not have the money to fill in the funding gaps themselves. The extensive subsidies and pricing regulation that would be required for the government to do so are inconsistent with their status as private entities. But these institutions will not be able to provide affordable pricing for students at all income levels without subsidies.

One alternative is to expand current financial aid programs, like increasing the Pell Grant. This approach can help reduce funding gaps at these institutions, but it may not eliminate them. We may need to be content with a system where these institutions are not accessible to all students regardless of need. Increasing educational opportunities, though, for more lower-income students to attend these institutions is still a worthwhile goal.

What is the role of pricing transparency?

A final, necessary element of this system is pricing transparency. Even if we implement a system where institutions charge prices students can afford, they need to know how much that is. Without this information, how can students and their families make appropriate enrollment decisions?

It would help if institutions charged prices based on a calculation of how much students can afford to pay, as displayed in Figure 1. If so, online systems could enable younger students to forecast the amount they are likely to pay before getting a definitive price as they approach the age of college entry. The key is that they pay what they can afford.

Creating that formula is no simple task, partly because there is no “right” answer in translating income and assets into an amount families can afford. Whatever approach we use, maintaining simplicity in such calculations is critical (although doing so isn’t always easy).

We also need to eliminate current practices that hinder pricing transparency. Setting a sticker price that few, if any, students pay as described earlier, provides one such example. Its use provides a marketing advantage for institutions, making it difficult for them to give up. It would take an agreement among schools to restrict this practice, an action that would almost surely (if unwisely) generate scrutiny from the Justice Department. Such scrutiny in this context would not increase competition in a way that lowers the price. Instead, it contributes to the lack of pricing transparency in the market that harms students.

Conclusion

The dual goals of excellence and affordability in our higher education system are difficult to achieve simultaneously. Institutions need incentives to strive for excellence, recognizing the impact of their decisions on affordability. Broadly speaking, our current system does not accomplish that. Achieving excellence and affordability will require significant changes.

The system I propose would move in that direction. The fundamental problem is insufficient resources at all but the most highly endowed private colleges. Where can additional resources come from? The simple answer is that they need to come from the federal government. The social benefits of a more educated society mean that such spending is a sound investment. Investments in higher education needs to be weighed against alternative uses of funds and the need to collect taxes to cover the cost. That said, this one seems worthwhile.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The Brookings Institution is financed through the support of a diverse array of foundations, corporations, governments, individuals, as well as an endowment. A list of donors can be found in our annual reports published online here. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions in this report are solely those of its author(s) and are not influenced by any donation.

-

Footnotes

- The actual size of the funding gap is determined by the difference between average expenditures per student, the amount students can afford to pay, and the distribution of students in the amount they can afford to pay. In essence, a third dimension is required representing the distribution of affordability across students. For simplicity, Figure 2 ignores this third dimension to simplify the point that there is a funding gap in the framework presented.

- For instance, recent free college proposals would only apply to those earning below $125,000. One might imagine that students with incomes higher than that would phase into making payments (like in Figure 2), but that would not change the basic concept conveyed in Figure 3.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How much should college cost students?

September 6, 2023

Key Takeaways: