The Israeli elections — an unofficial referendum on the tenure of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu — ended Tuesday in a clear endorsement of the prime minister by Israeli voters.

With over 99 percent of the votes counted, Netanyahu’s Likud leads with 29 or possibly 30 seats in the 120-seat Knesset, compared to 24 for the center-left Zionist Union. Netanyahu will head the next Israeli government, very likely a government made up of right-wing, religious, and centrist parties.

In democracies, incumbents lose more than challengers win. And this time, Netanyahu avoided fumbling away power, defying early speculations of his defeat in part because of the relative weakness of his challenger. Zionist Union leader Isaac Herzog is an able and respected politician, but he is not a naturally charismatic leader, nor was he able to capture the Israeli imagination with a new message.

Herzog’s challenge, from the start, was to capitalize on Netanyahu’s electoral weaknesses on domestic policy, while limiting his own weaknesses on national security and foreign policy. Much of the competition was, therefore, a battle to set the agenda: Netanyahu traveled to Washington to drive home his message on Iran, with some added political benefit, while Herzog focused his campaign around socioeconomic issues.

As is the norm in Israel, foreign policy determined the prime minister, returning Netanyahu to power. A new Netanyahu government means that Israel will continue its vehement opposition to U.S. policy on Iran, and its bitter feud with the White House. It will also mean a looming crisis of governance for the Palestinian Authority (PA) in the West Bank, which faces an acute financial crisis due to lack of donations and because Israel has withheld Palestinian tax money in retaliation for the PA’s moves in international organizations intended to isolate Israel. These international moves will likely only intensify now.

Socioeconomic issues, however, determined the powerbroker of Israeli politics: Moshe Kahlon of the new centrist Kulanu party, which claimed 10 seats. Assuming Netanyahu does not want to form a broad-based national unity government, he will need Kahlon’s support to assemble a governing coalition.

Responding to Kahlon’s demands, Netanyahu offered him the Finance Ministry even before the election, saying he would tap the former Likud minister for the slot regardless of how many seats Kulanu won. If Kahlon takes up the post, he will have an opportunity to lead a bold reform agenda aimed at increasing competition in Israel’s centralized economy and lowering the cost of living. The Ultra-Orthodox are also likely to re-enter government after a two-year hiatus, sending former Finance Minister Yair Lapid to the opposition and undoing much of his secularist agenda.

The mechanics

Here’s how Israeli elections work: Israelis vote for parties, not individuals, in one national district. Each party puts forward a list of candidates, in rank order, and each voter chooses one list at the polls. The 120 seats of the Knesset are then divided among the lists in proportion to the national vote share each party receives, provided the party passes a minimum threshold (now equal to 4 seats).

The result is a highly representative, but highly fractured political system. At least ten factions will serve in the incoming 20th Knesset, representing a wide range of ideological positions and demographic constituencies. In this system, minorities of all kinds — including Israel’s large Arab minority — are represented in parliament, but no single party has ever succeeded in garnering more than half the seats. Consequently, coalitions must be formed, and meticulously maintained, in order to govern; early elections, usually the outcome of a failed coalition, are the norm rather than the exception.

When the final results of the election are published, each party will send representatives to Israeli President Reuven Rivlin to recommend one Member of Knesset (MK) as the next prime minister. If one MK receives more than 60 recommendations — as Netanyahu likely will — the president will task that MK with negotiating a new coalition and earning the confidence of the Knesset.

The results

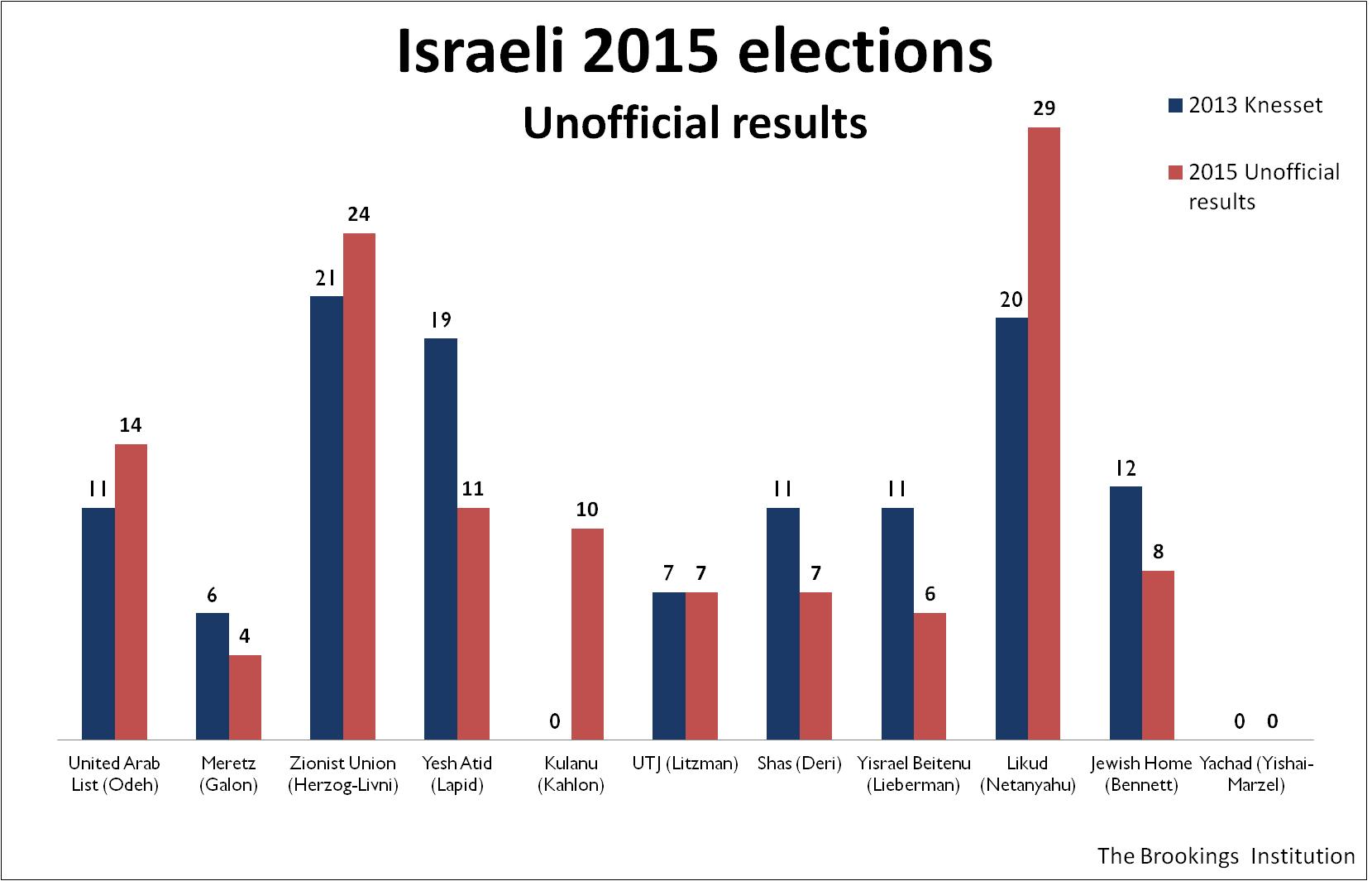

Figure 1 depicts the unofficial results (the count with 99 percent of precincts reporting) on a rough (and somewhat arbitrary) left-to-right axis. Note that in Israel “left” refers to parties that are dovish on the Palestinian issue and the Arab-Israeli conflict, and “right” means hawkish on these issues. Both the left and right camps include parties of many different economic and social outlooks.

In the week leading up to the election there was a leftward momentum that suggested the Zionist Union, an amalgam of the Labor party headed by Isaac Herzog and Hatnua party headed by Tzipi Livni, would pull ahead of Netanyahu’s Likud.

In response, Netanyahu embarked on a last minute campaign to rally the right-wing to the Likud. He set aside his own commitment to the two-state solution, implying (and later denying) it was “irrelevant,” and later making clear that a Palestinian state would not be created on his watch. On election day, the Likud even turned to (unfounded) claims of a supposedly illegitimate campaign to get out the vote among Israel’s Arab minority, which generally opposes Netanyahu.

This campaign succeeded remarkably. The Likud not only closed the gap with the Zionist Union, it far surpassed it, doing so by siphoning votes away from its right-wing allies, in particular the Jewish Home headed by Naftali Bennett.

In theory, this rally did not fundamentally change the math between the blocs in the Knesset — a Herzog government is still mathematically, though not politically, possible.

The Joint List, which for the first time united highly disparate parties representing the Arab minority, also experienced success, becoming the third-largest bloc with 14 seats. Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid, though it did not repeat its 2013 performance, also did surprisingly well, claiming 11 seats. Leftist Meretz narrowly avoided falling below the minimum threshold to win representation in the Knesset, it appears, and Yisrael Beitenu, the corruption-scandal-ridden party of Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, survived, though bruised. It’s very unlikely Lieberman will be the next foreign minister, as he lacks the leverage he once had to secure such a senior post.

Election Day was full of acrimony between Israel’s Jewish majority and the Arab minority among its citizens. But at the end of the day, if these numbers hold, Israeli voters also gave an important boost to political decency. The Yachad list of Eli Yishai — which included Baruch Marzel, formerly the chairman of the racist Kach, outlawed as a terrorist organization by both Israel and the United States – did not receive the minimum 3.25 percent of the vote necessary to win Knesset seats.

Earning a presidential mandate to form a government

The stage now turns to the presidential residence, where Netanyahu will work to gain the recommendation of the elected factions.

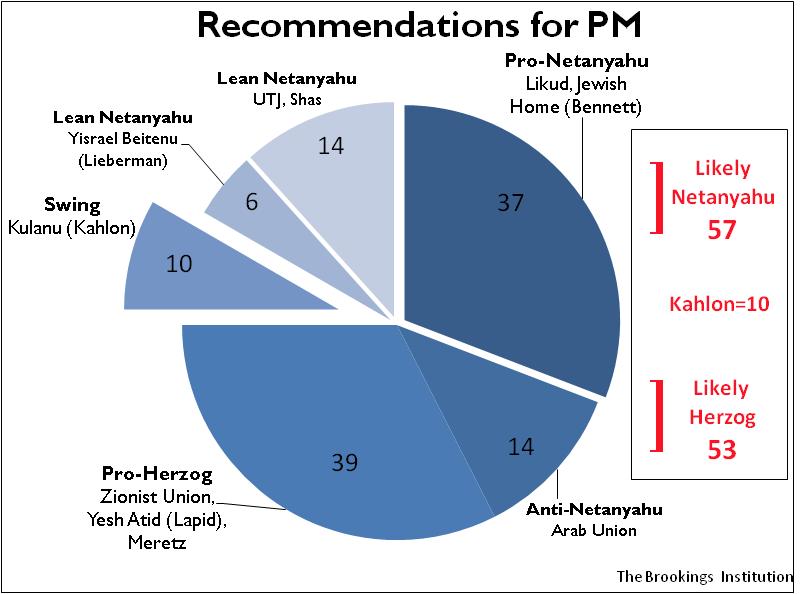

As shown in Figure 2, the unofficial results give the Netanyahu- and Netanyahu-leaning camp 57 seats, just four shy of the goal. Herzog could potentially earn the support of 53 recommendations (the Arab Joint List would likely recommend Herzog if he had a realistic chance of forming a government, though they may abstain in the current situation). With neither side clearly above 60, these totals leave a new powerbroker in the Israeli politics: Moshe Kahlon.

Kahlon himself is a former Likud minister who made a name as communications minister in Netanyahu’s cabinet, starting in 2009. He introduced competition to the mobile phone industry, lowering prices dramatically. His popularity was such that Netanyahu even urged his other ministers to “become Kahlons.” But when Netanyahu refused to appoint Kahlon as finance minister in late 2012, Kahlon left the government and the party.

This caused a personal rift between Netanyahu and Kahlon, and the two leaders face substantive differences as well. Netanyahu’s economic policy, for Kahlon, represents harsh neo-liberal economics, in contrast to the more compassionate-conservative approach Kahlon espouses. He promises to introduce competition to the banking industry, with far more powerful vested interests than the mobile phone industry, as well as the housing market. To do all this, Kahlon has demanded the finance ministry — and is very likely to get his wish.

Given Kahlon’s profound differences with Netanyahu — which sufficed to cause him to break with the Likud, where he was a rising star — he may have wanted to depose the prime minister. And if the Zionist Union had been significantly bigger than the Likud, as some polls suggested, this could have provided Kahlon the necessary political cover to choose Herzog over Netanyahu.

Kahlon, however, may also wish to return to the Likud in the future, and a betrayal of the party in favor of its left-wing rival would not easily be forgiven by the Likud membership. He may have been planning to side with Netanyahu all along.

A right-wing coalition

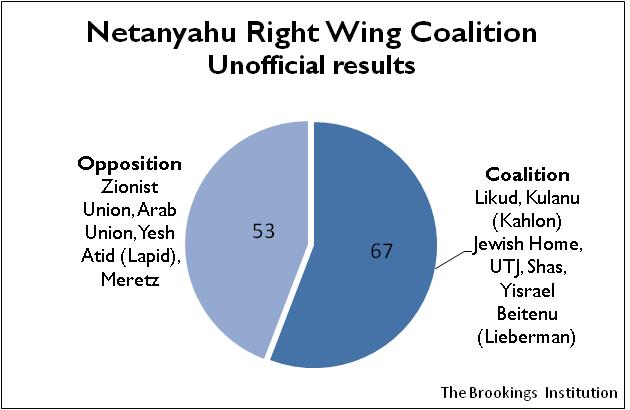

Either way, with a decisive Likud advantage, Kahlon will side with the victor — Netanyahu. The most likely outcome is now a right-wing and religious coalition with Netanyahu at the helm, bringing in Jewish Home, the Ultra-Orthodox United Torah Judaism (UTJ) and Shas, Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu and Kahlon’s Kulanu. With 67 projected seats, such a government could earn the confidence of the Knesset and would offer relative stability.

A theoretical Herzog coalition

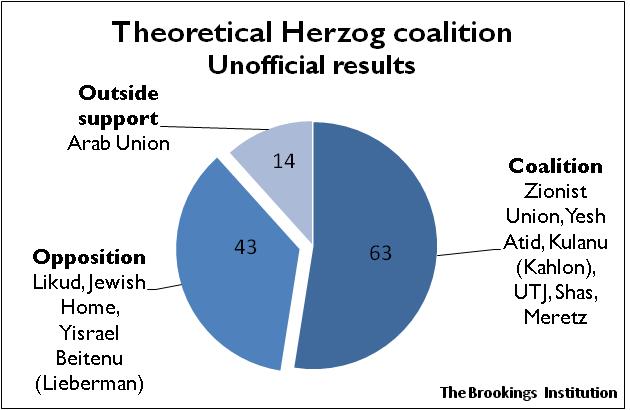

In theory, Kahlon could still decide to side with Herzog, as shown in Figure 4. But Herzog would still not be able to form a coalition unless UTJ agreed to join alongside Lapid, something they have vowed not to do. With a narrow 63-seat base, moreover, a Herzog coalition would have been very shaky, especially on issues of religion and state that divide the Ultra-Orthodox and the secular Lapid.

Despite much speculation abroad, the Arab Joint List, as such, would not join the coalition, but it could have offered some outside support, as Arab parties did between 1992 and 1996, during the governments of Prime Ministers Yitzhak Rabin and Shimon Peres.

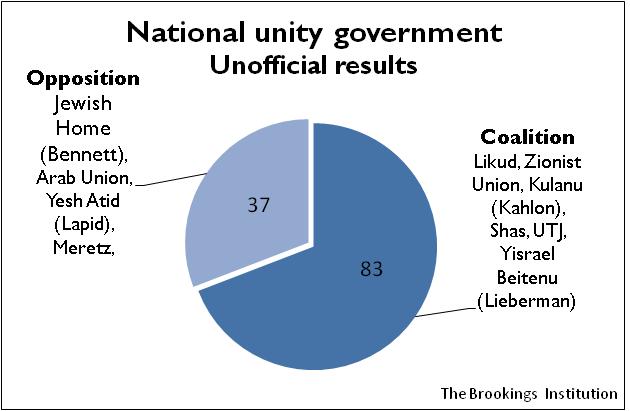

National unity government

In the lead-up to the elections, Kahlon and Lieberman stated their preferences for a third option: a national unity government that included both the Likud and the Zionist Union. Given the election results, this government would be led by Netanyahu.

Such a government is still possible, in theory, and would enjoy a very wide base, but it would be pulled in two very different directions by the right flank of the Likud and the left flank of Labor. Likud hawks are vehemently opposed to a two-state solution, while Laborites remain strong supporters of peace with the Palestinians. Labor leftists are economic social democrats and some are even socialists, while Netanyahu is a proud neo-liberal of the Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher brand.

Moreover, the Israeli public, deeply divided politically, is hostile to the idea of a national unity government. In a recent poll, 53 percent opposed the idea, while only 23 percent supported it.

If Kahlon or Netanyahu chose to go this route, however, they would find support from Rivlin. The Israeli president has stated his preference for a national unity government tasked with reforming Israel’s electoral system, to try to introduce more stability. The reform would likely include designating the leader of the largest party as the automatic prime minister, which would produce an incentive for voters to support the larger parties — and thus influence the identity of the prime minister — and encourage parties to join forces ahead of elections.

It appears clear, however, that this is not Netanyahu’s preference. He has already reached out to the Jewish Home, on the far right, and this would likely preclude including the Zionist Union in the coalition.

The gamble Netanyahu took in going to elections — a gamble that was politically risky– paid off dramatically for the prime minister. Netanyahu is currently Israel’s second longest serving prime minister, after the founding leader David Ben Gurion. Should Netanyahu’s tenure survive until 2018, he would pass Ben Gurion.

However, Ben Gurion’s record appears safe for now. If history is any guide, the 20th Knesset, like the 19th, will likely not see its term through. In Israel’s political system today, the only thing that seems constant is further instability.

This article was originally published in Foreign Policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How Bibi pulled it off

March 18, 2015