Progressives worry that growing income inequality is concentrating both wealth and political power in the hands of elites. The Tea Party worries that government is out of touch with ordinary Americans. For two groups with widely divergent political views, these concerns are surprisingly similar: both think our representatives are unrepresentative.

Ideally, the House of Representatives ought to reflect America’s diversity by including individuals from a wide variety of social and economic backgrounds. The House, in particular, is supposed to be “the people’s chamber,” whereas the Senate was designed as an elite institution.

On this blog, we focus on issues of economic, social and educational inequality–and in particular on intergenerational mobility. As we approach the November elections, it seems a good time to ask, with regard to a series of mobility-relevant indicators: How representative is the House of Representatives?

HOUSE OF CAPITAL?

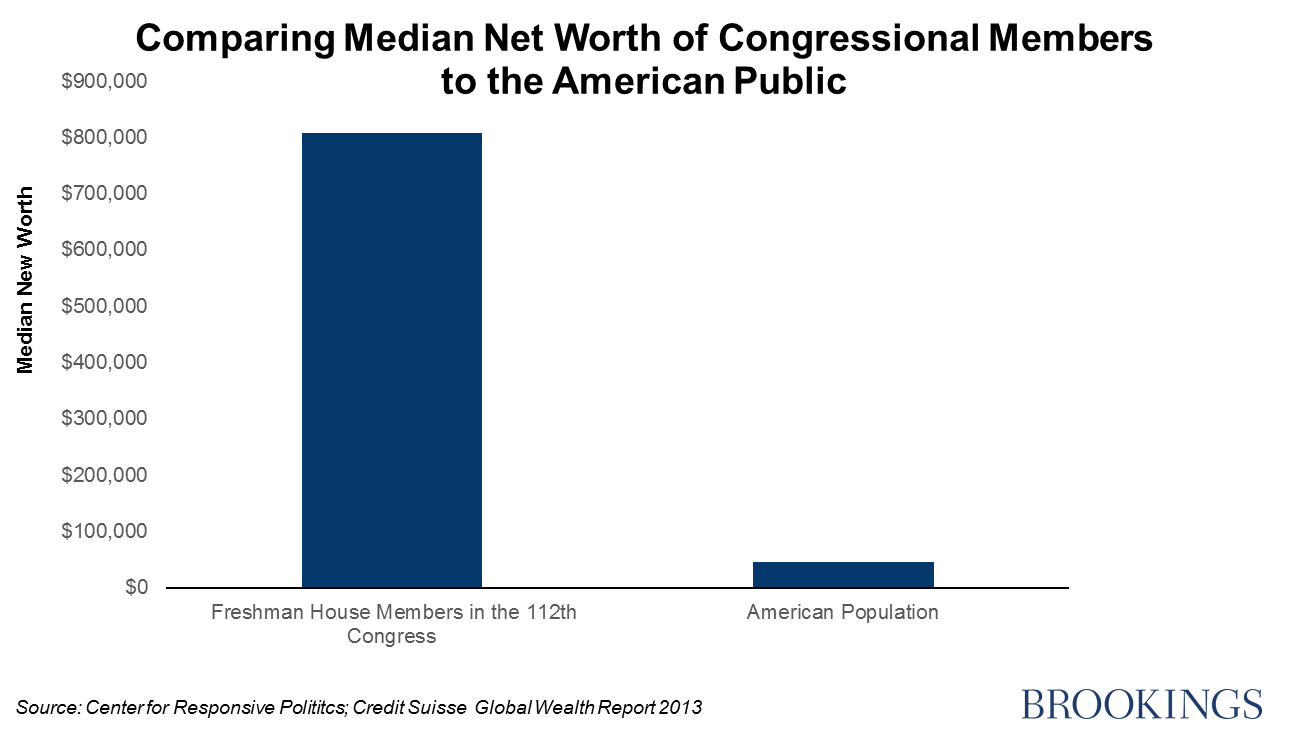

Let’s start with money. The House is much wealthier than the rest of the country and wealthier than past Congresses. In the 112th Congress as a whole, most members are millionaires, according to data from the Center for Responsive Politics. The freshman House members in the 112th Congress had a median net worth of $807,013; last year, the median American was worth $44,900.

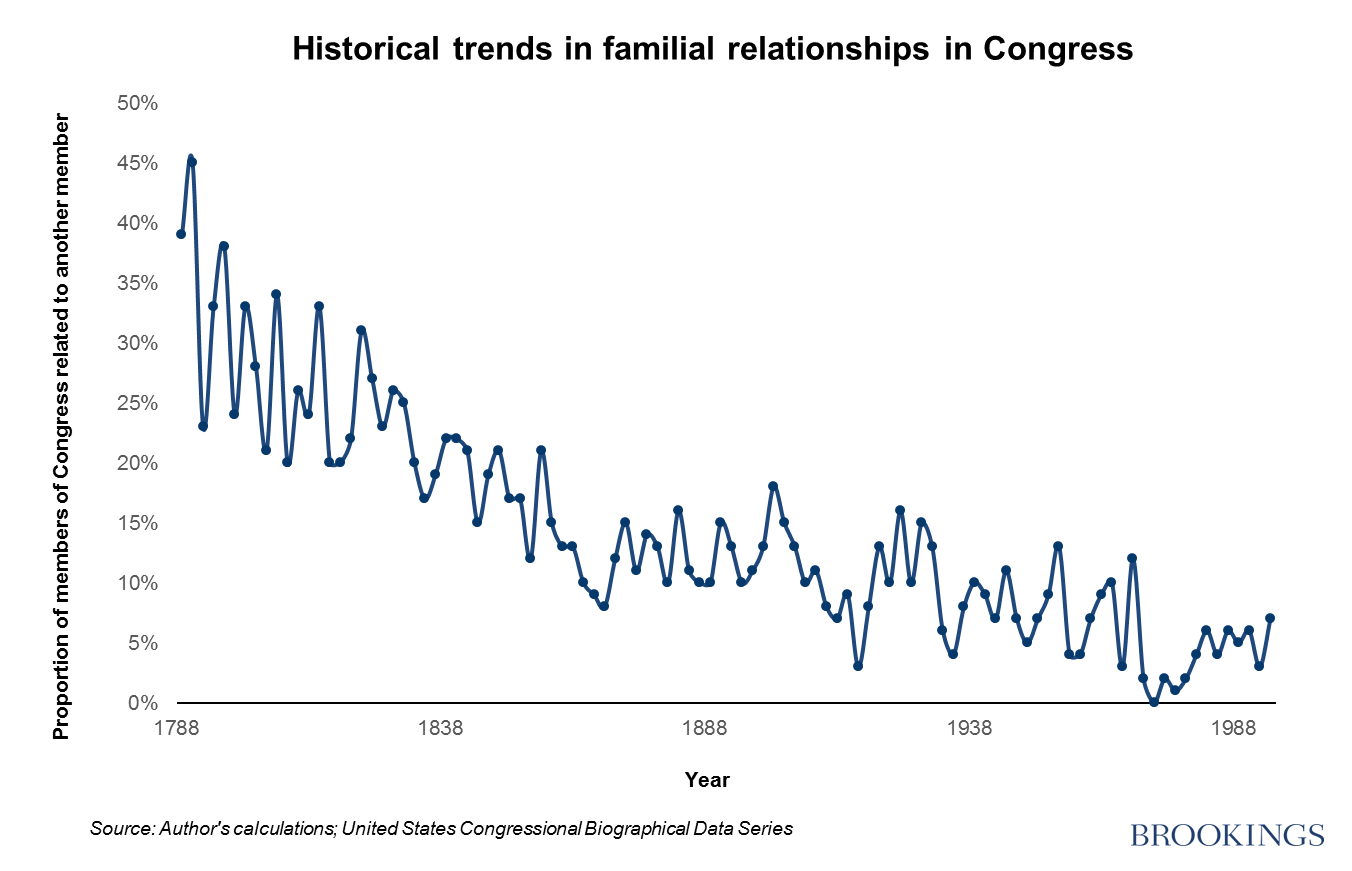

Wealth in adulthood does not necessarily indicate a privileged start in life. Perhaps our representatives rose from rags to riches, and their recent wealth obscures less-affluent childhoods. After all, the House is becoming more representative by race and gender. There is also less overt nepotism, with a sharp drop over time in the proportion of freshman members who are related to other members of Congress:

UPWARDLY MOBILE CONGRESSMEN?

We attempt to determine how many of Congress’ members started life near the top of the economic ladder by looking at two education-based measures (which may serve as proxies for their family income during childhood):

- Private high school attendance: Children whose parents can afford private school probably enjoy other advantages as well, such as safer neighborhoods, outside tutoring, and access to job networks. Those resources tend to perpetuate class divides, as richer parents hoard them, while poorer parents struggle to obtain them.

- Community and state college attendance rates for the 112th Congress: For poorer students who cannot afford private tertiary education, local and state colleges facilitate upward mobility by offering a pathway to the middle class. We therefore examine how many House members attended community colleges and state schools.

We use the United States Congressional Biographical Data Series to observe trends among freshmen House members from the 1st to the 104th Congress, which convened in 1995, and added data for subsequent years through our own internet searches. Lindsey Burke, at the Heritage Foundation, generously provided data from her 2009 report on private high school attendance in the 111th Congress.

PRIVATE K-12 SCHOOLING

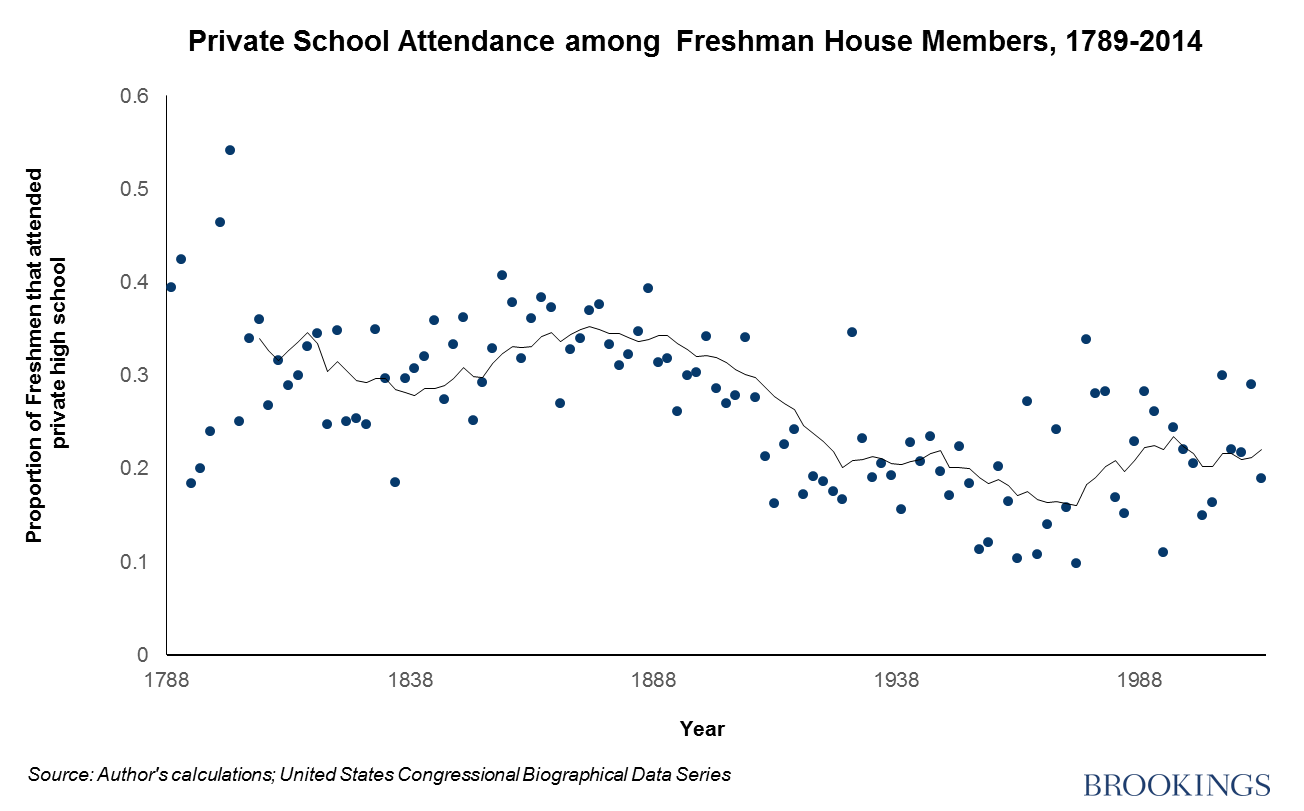

Since the first Congress convened in 1789, private high school enrollment has fallen among freshman House members. Some of the lowest data points appear after the 86th Congress, which began in 1959:

The expansion of the public school system surely explains the decline in private school attendance. The average freshman in the 86th Congress was 53, which means he was 14 in 1920. The public school system exploded in the 20s and 30s. In 1925, for example, 30 percent of children between 14 and 17 attended high school, and public schools served 93 percent of them. By 1940, half did so.[1] And because House members are mostly white, they had earlier access to quality public education than these numbers suggest, because the national average includes people of color.

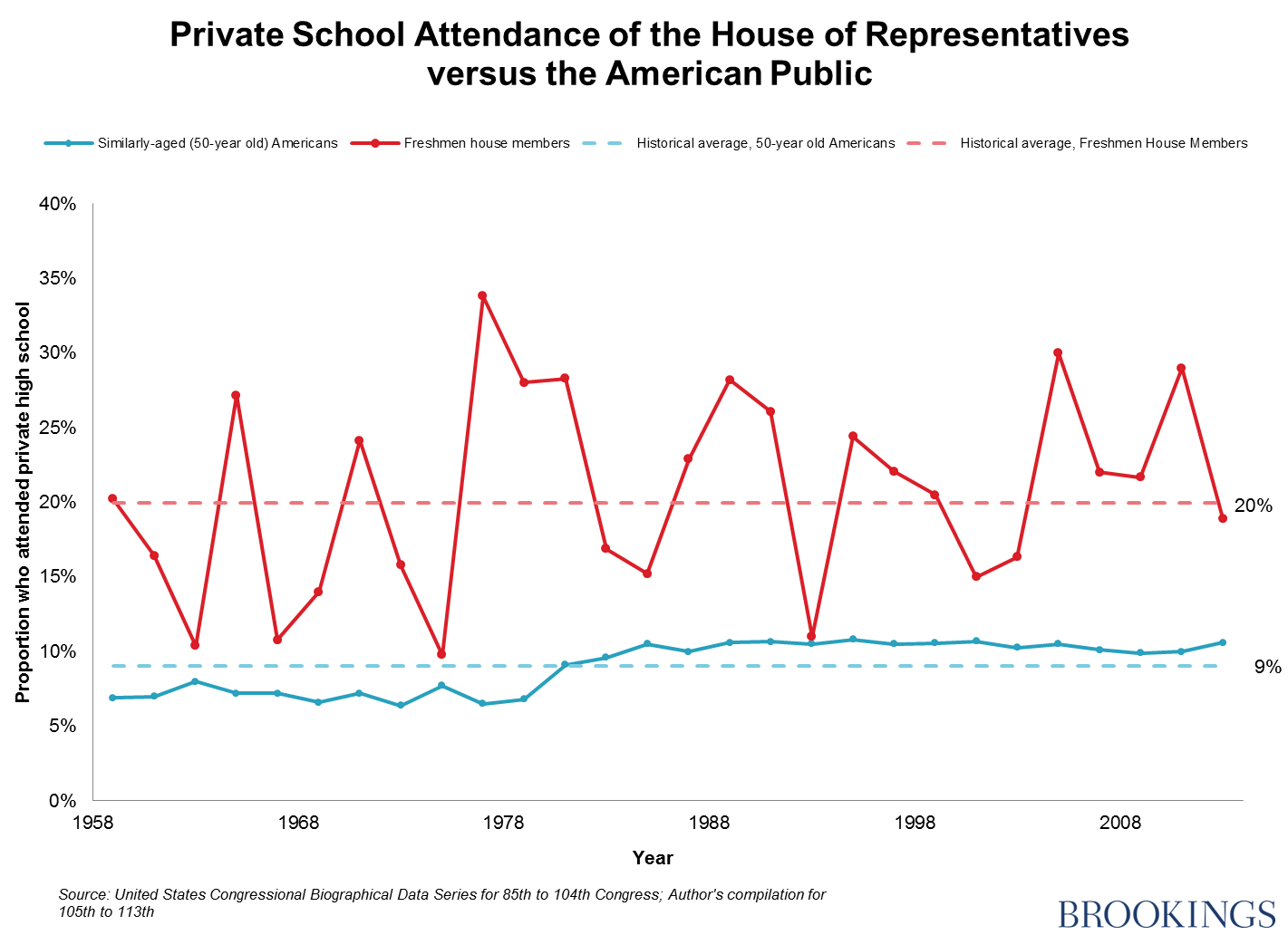

We therefore look in more detail at the educational backgrounds of more recent House members, starting with the 86th freshman class—one of the first cohorts to have widespread access to public high schools. We compare the proportion of freshman House members who went to private high school to the prevalence of private high school attendance among Americans who were 50-years old in the same year (the approximate peer group of freshman house members).

The data are noisy, because new classes tend to vary in size and are generally small. Across the years in question, the freshman members’ rate of private high school attendance has been a little more than twice the national average: 20 percent versus 9 percent.

Overall, the difference in rates of private school attendance between Americans and their representatives appears relatively constant. Congress isn’t receiving more private-school graduates than before, but public school graduates, presumably from more ordinary family backgrounds, haven’t flooded Capitol Hill, either. Despite huge investments and improvements in public school education, the balance between privately and publicly educated congressmen has been unchanged for half a century.

COLLEGE EDUCATION: WHICH ALMA MATERS?

Almost all (99 percent) of the freshmen members of the 112th Congress have a college degree: by comparison, only a little over a third (37 percent) of today’s 45 to 64 year olds have anything more than a high school education. But we should neither expect nor desire the educational make up of Congress to mirror that of the rest of the country; we want our legislators to be well-read. Perhaps the only danger with a House so dominated by college graduates is a lack of attention to other forms of educational advancement, such as vocational courses or apprenticeships.

But it may matter which colleges congressmen went to, not least in terms of indicating diversity of background. Private colleges have much heftier price tags than state or community college. So determining whether a House member received their college degree from a community college, a state college, or a private college is likely to tell us something about their own background. Community college and state schools serve as a bridge out of poverty for many Americans because they are relatively affordable.

The freshmen members of the 112th Congress were college-age around 1980. Of those who attended college, 6.5 percent did so at a two-year institution, compared to 28 percent of the same cohort of the general population. Half the freshman members with college degrees went to state schools (50 percent), compared to three out of four (76 percent) Americans of the same cohort. And while almost one in ten (9 percent) of freshman House members attended an Ivy League college, fewer than 2 percent of the general population did.

The educational backgrounds of House members suggest that they’re not only richer than the average American as adults, but come from more affluent families, too. This gap is stubbornly persistent, at least judging from our benchmarks.

FIVE CONGRESSIONAL HORATIO ALGER STORIES

But there are some notable exceptions. Using our own entirely subjective “lowly beginnings” indicator, we picked out the top five “Horatio Alger” freshman House members in the 112th and 113th Congresses:

- Jim Renacci (R-Ohio) – raised by a railroad worker and a nurse and was the first in his family to attend college.

- Sandy Adams (R-Fla.) – worked two jobs while obtaining her GED as a single mother—the exception to the “GED earners have less grit rule”.

- Hansen Clarke (D-Mich.) – lost his father at 8 and raised by his mother, a crossing guard.

- Tony Cardenas (D-Calif.) – father immigrated from Jalisco, Mexico and worked the fields of California’s Central Valley to support his 11 children.

- Kyrsten Sinema (D-Ariz.) – spent more than two years of her childhood in an abandoned gas station while her stepfather was between jobs.

Given the generally more comfortable backgrounds of new House members, those who fought their way up against the odds provide an important dimension of diversity.

DOES THE BACKGROUND OF REPRESENTATIVES MATTER?

Does it matter if our Representatives are not wholly representative in terms of wealth or background? One obvious danger is that the views of the less fortunate and/or less affluent are not adequately represented. In general, affluent opinion departs from popular opinion. While four in five (78 percent) Americans believe that the minimum wage should “be high enough so that no family with a full-time worker falls below the poverty line,” just two in five (40 percent) of the wealthiest 4 percent agree, according to Larry Bartels and his colleagues at Northwestern University. Wealthier Americans are also more likely to perceive the budget deficit as a “very important” problem, compared to unemployment or education.

Caution is required here. First, we cannot automatically read across from personal wealth to the political opinions of politicians. Second, while Congress is not, on our measures, highly representative, it is also far from a monoculture of privilege. But as we strive to close the opportunity gaps faced by so many Americans, and seek policies that promote social mobility, we should pay at least a little attention the backgrounds of the lawmakers themselves.

[1] Boyer, Ernest L. High School: A Report on Secondary Education in America. New York: Harper & Row, 1985. Print.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).