Typical Keynesian macroeconomic theory would recommend that policymakers conduct expansionary fiscal policy in bad times to stimulate the economy and contract fiscal policy in good times to cool down the economy (i.e., countercyclical fiscal policy). Most of the industrial world has conducted this type of stabilizing fiscal policy for a long time; yet, most developing countries have failed to do so over much of their history.

Indeed, contrary to Keynesian recommendations, the developing world has typically followed procyclical fiscal policies that involve expanding fiscal policy in good times and tightening fiscal policy in bad times. Figure 1 shows that the correlation between the cyclical components of government spending and real GDP (i.e., the longer-term trends have been removed) is overwhelmingly positive (indicating procyclical spending policy) in developing countries (yellow bars) but negative (indicating countercyclical spending policy) in industrial countries (black bars). This difference is striking. Unfortunately, for developing countries, procyclical fiscal behavior reinforces output fluctuations, exacerbating booms, and aggravating busts.

Figure 1. Correlation between the cyclical components of real government spending and real GDP

Why has fiscal policy been procyclical in developing countries?

Traditional explanations for this poor fiscal behavior have revolved around two main arguments. The first argument points to political distortions and weak institutions. Policymakers’ shortsightedness and political pressures to spend when resources are plentiful, among other political economy-based considerations, encourage “excessive” public spending during good periods, leaving few resources to spend in bad times. The second argument emphasizes the effect of limited access to international credit markets, particularly in bad times. While one could think of several countries that have governments that are isolated from international credit markets on a regular basis, contemporary history suggests that, in most cases, countries lose access to international credit markets or undergo high sovereign spreads in bad times as a consequence of fiscal profligacy and indebtedness during good times. Consequently, most literature on this issue has developed around the explicit or implicit notion that fiscal procyclical behavior is the inevitable result of political economy forces and weak institutions.

The history of fiscal policy in Latin America and the Caribbean

The Latin America and the Caribbean region has not escaped the procyclical trap that has prevented the developing world from using fiscal policy as a stabilization tool. While the above characterization may convey the impression of a permanent problematic state of affairs, the opposite is true. Far from being a static phenomenon, the conduct of fiscal policy over the business cycle is a dynamic process that constantly changes as policymakers learn from previous traumatic episodes and others’ successful experiences.

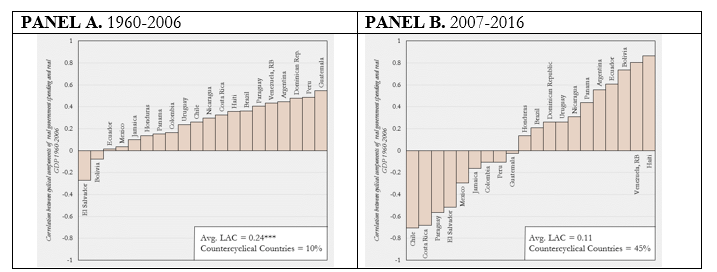

At the same time, improvements in domestic political institutions and easier access to international credit relaxed some of the constraints that countries have faced in the past. While victory is far from assured or universal, recent evidence from the past boom-bust cycle indicates that several countries (for example, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru) have been able to save more fiscal revenues during the commodity-super phase of the cycle. This has enabled them to handle, this time with larger fiscal spaces, the global financial crisis and the recent low growth scenario. As shown in a recent World Bank report (see Figure 2), while most countries in the region (18 out of 20 countries, or 90 percent) pursued procyclical fiscal policies before 2007, a marked shift occurred in response to the global financial crisis. In fact, the share of countries conducting procyclical fiscal policy decreased from 90 percent to 55 percent (or 11 out of 20 countries).

Figure 2. Latina America and the Caribbean’s procyclical policies before and after the global financial crisis

What forces and policy actions lie behind this important shift in the region? The answer is, naturally, a complex one and, therefore, it proves difficult to identify a single “silver bullet” policy change. Rather, a combination of improvements and transparency in the budgetary processes, better bureaucracies and institutions, and higher degree of public scrutiny are some of the key (yet difficult to measure) forces behind this fundamental change.

As discussed, a key element in escaping the procyclical trap relies on the ability of governments to save and build fiscal space in good times. After all, it is futile to conduct procyclical fiscal policy during good times (e.g., spend more using larger fiscal revenues originated in larger tax bases, be it income or consumption) and countercyclical fiscal policy during bad times (in an attempt to help the economy to recover) without clashing with fiscal sustainability. In this respect, fiscal rules might provide policymakers the most needed safeguards to avoid “excessive” spending during good times.

While a cliché, there is no better and trusted way to prepare for the bad times than to be prudent in good times. An enforceable structural fiscal balance guarantees just that. It is no coincidence then that these types of fiscal rules are spreading within Latin American and the Caribbean. While the use of structural fiscal balances rules is relatively new to the region, anecdotal evidence suggests that its implementation and use have helped both fiscal authorities and economic agents to focus on the right target, the structural fiscal balance, which helps in avoiding procyclical tendencies.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Has Latin America learned to use fiscal policy to stabilize the business cycle?

November 2, 2017