For many cities and towns throughout the United States, the vision of economic success has long resembled places like Silicon Valley. This vision consisted of high-wage jobs, often in high-technology industries, available to as many workers as possible. But over the last decade, it has become clear that the Silicon Valley model of economic development does not work for most places. Perhaps it’s not even working for Silicon Valley, where wage inequality has soared and affordability issues abound. In a recent poll, 47% of residents there said they were likely to move out in the next five years.

But there is an alternative. Far from Silicon Valley, Grand Island, Neb., population 53,000, represents a different path to economic development—one where the middle of the labor market is stronger and economic mobility is higher. At first glance, Grand Island might seem like an ordinary small Midwestern city. It has a diversified economy comprised of manufacturers across sectors and a regional hospital system. The average single-family home goes for well below the national median price.

For decades, places like Grand Island have been associated with the economic struggles of the Rust Belt: declining populations, declining employment opportunities, and a declining middle class. But this region is different. The middle class in Grand Island has grown since 1980, as has its manufacturing economy. As wages stalled for U.S. workers without a four-year degree—which is to say, most workers in our economy—between 1980 and 2019, wages for non-college workers in Grand Island grew approximately as fast as wages grew for those with a college degree: by more than 36%. And upward mobility in the Grand Island region has been well above the national average.

With so much attention still centered on the dramatic growth of innovation economies in places like Silicon Valley and Austin, Texas, it’s easy to miss signs of economic progress in places like Grand Island. But there are many regions similar to it across the United States. Our research has identified more than 100 places where the middle of the job market is strong and upward mobility is high. These places are much smaller than the average city, and are concentrated in the Midwest in states from Minnesota to South Dakota down to Nebraska and Texas.

Our analysis suggests that strong economic outcomes in these regions aren’t just a happy accident. They are linked to industries and public policies from which other regions can learn. In recent years, coverage of inflation and COVID-19 shocks has tended to overlook a string of good news for American workers. Tight labor markets and increased investment in manufacturing—aligned with a decrease in wage inequality—represent economic tailwinds favoring the growth of high-quality middle-wage jobs across the United States.

What are middle-wage jobs, and where are they found?

Economic growth for the middle class, centered mainly on access to good jobs, is a bipartisan priority among state and local economic development officials. But as recent Brookings analysis and engagement with practitioners has underscored, it’s not always clear what the concept of “good” jobs means in practice.

So, let’s look to the middle: In our research, we define middle-wage jobs as occupations with a median wage in the middle-third of the income distribution. In 2019, for example, middle-wage occupations earned hourly wages between $13.65 and $26.93 nationally. Of course, people employed in these occupations might earn more or less depending on the prevailing local wages for those occupations.

|

Occupation groups (Descending in average wage) |

Middle-wage jobs as a share (%) of total jobs in occupational group |

Middle-wage jobs in occupational group as a share (%) of total middle-wage jobs |

|---|---|---|

|

Managers and executives |

3.57% | 1.46% |

| Finance, advertising, sales | 27.05% | 18.32% |

| Technicians, fire, and police | 46.35% | 7.67% |

| Clerical and administrative support | 79% | 28.94% |

| Production and operative | 71.66% | 14.71% |

| Transportation and logistics | 56.84% | 14.32% |

| Construction and mechanics | 51.04% | 10.94% |

| Cleaning and protective services | 18.61% | 2.55% |

| Personal services | 1.16% | 0.3% |

| Health services | 6.73% | 0.59% |

| Farm and mining | 2.19% | 0.18% |

As Table 1 highlights, just five occupation groups make up more than 85% of middle-wage jobs: 1) finance, advertising, and sales; 2) clerical and administrative support; 3) production and operative (which includes manufacturing); 4) transportation and logistics; and 5) construction and mechanical jobs. In the production, transportation, and construction groups, middle-wage jobs make up the majority of all jobs in the category. For example, among production workers, over 70% of all jobs are middle-wage.

We define regions growing from the middle out as those places where middle-wage jobs have grown compared to high-wage and low-wage jobs in recent decades. These are regions where the middle of the labor market has become stronger, in contrast to the overall “hollowing out” of the middle at a national level beginning around 1980.

Not all of these middle-wage jobs are created equal. Some jobs are relatively evenly spread across the country, such as clerical jobs in non-tradable sectors such as retail, while others are in tradable industries (which export beyond the region and import goods and services to it) that tend to cluster in some places more than others while delivering high multiplier effects that spill over to the rest of the local economy. Major tradable industries include agriculture, manufacturing, and high-technology services such as software companies. The opportunities for regions to grow their middle-wage jobs tend to be in tradable sectors that are characterized by higher innovation and productivity and where new entrepreneurial activity or surges in new investment can reshape the local labor market and even raise wages in the local service sector.

What does growing from the middle out require, and what makes it possible?

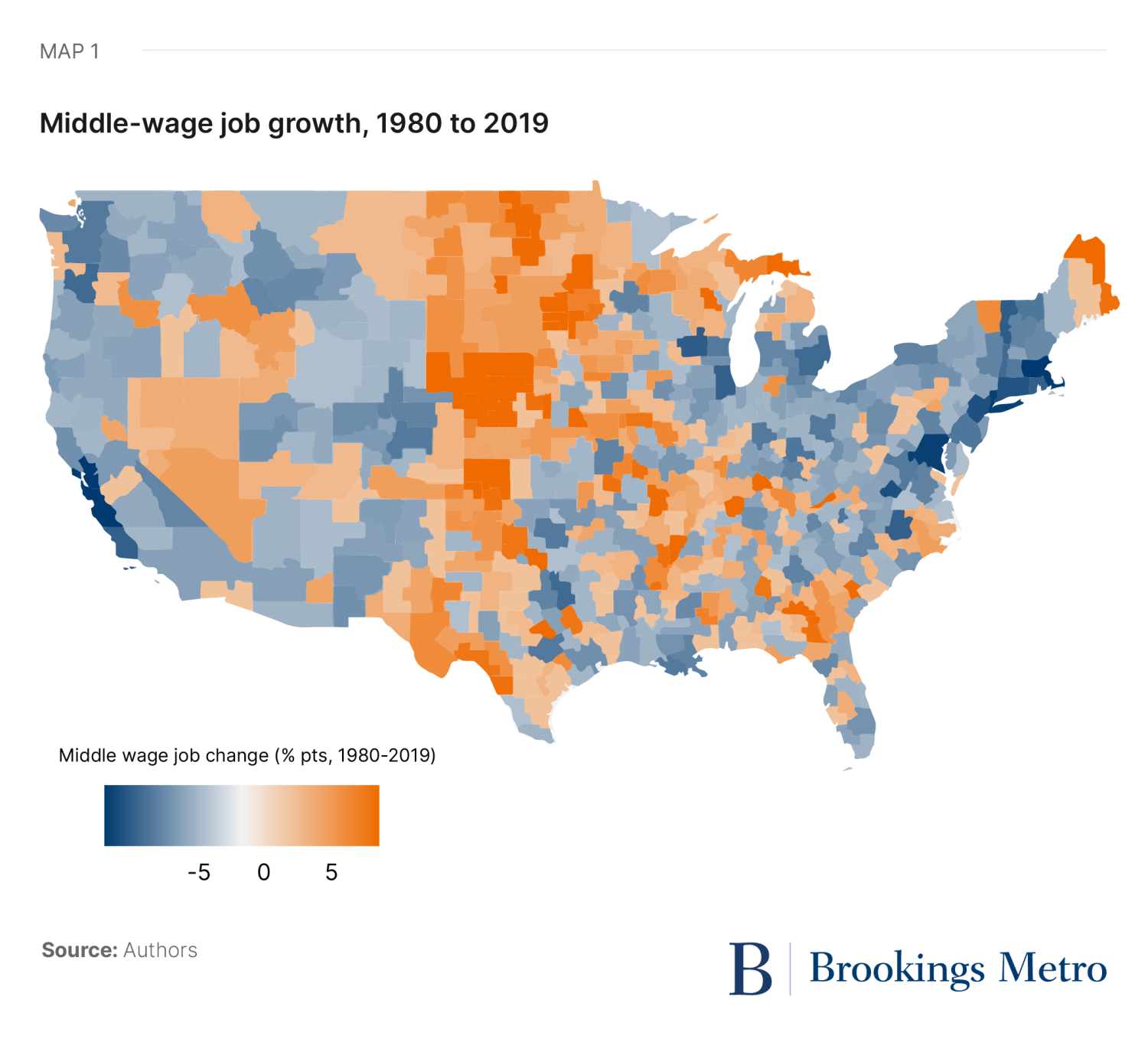

Since the 1980s, regions growing from the middle out have been concentrated in particular areas of the country. Whereas high-wage, high-tech growth has been concentrated in large metro areas along the East and West coasts, our analysis finds that growth in middle-wage jobs has occurred in a central corridor of mostly small regions that cluster in a vertical band traversing the country down the middle. The top of the corridor starts just below Minnesota, before stretching through the Dakotas, Nebraska, Iowa, Oklahoma, and southward into Texas.

Map 1 maps the growth of middle-wage jobs in commuting zones, aka regional labor markets, in the American heartland, compared to the severe hollowing out of middle-wage jobs relative to high-wage and low-wage jobs along the coasts. But when it comes to generating opportunity, growth in a region’s share of middle-wage jobs only matters if those jobs are linked to other positive outcomes, such as higher upward mobility or increased wages for workers without a college degree. Our research is interested in whether middle-wage job growth between 1980 (the onset of sharp job market polarization) and 2019 has been associated with other good outcomes for regions.

We find mixed results. First, there’s the hollowing out: Regions with the fastest income and population growth have been associated with a decline in middle-wage jobs. This should be unsurprising given the trend toward hollowing out among large coastal economies, particularly those such as the Boston, Seattle, and San Francisco-Oakland-San Jose regions, which have experienced concentrated growth in high-tech jobs.

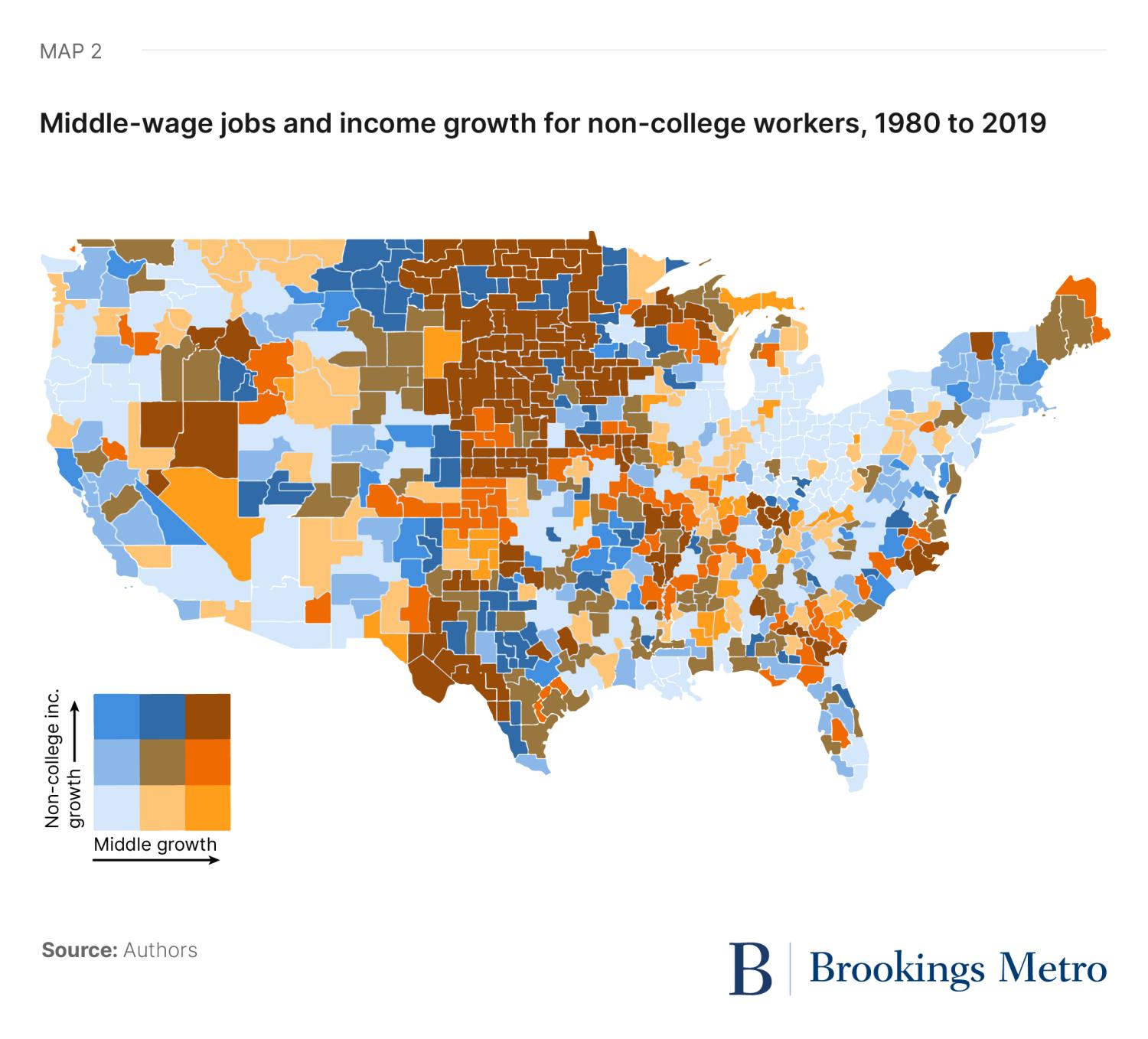

But places with middle-wage job growth have been associated with higher upward mobility— defined as the expected economic outcome for a child born into a lower-income family—as well as higher income growth for workers without a college degree. And when we mapped regions’ growth in middle-wage jobs as well as their growth in non-college income growth, we found the same central corridor regions experiencing the highest growth in their share of middle-wage jobs and the highest growth in incomes for those without a college degree (see Map 2). Although we can’t determine from the data whether these factors are causally linked, the positive association suggests that growing middle-wage jobs in a region is indeed associated with other desirable economic outcomes.

What policies and development strategies might grow the middle?

The regions in the central corridor can serve as a model for other places in the heartland looking to grow from the middle out. When we searched for characteristics that differentiate the regions with high middle-wage job growth and high upward mobility, for example, our data pointed to key three factors: educational performance, relatively high social capital, and manufacturing presence.

First, the central corridor regions often have strong K-12 education scores, but a low share of four-year college degrees. These regions are good at preparing their workers for middle-wage jobs that do not require a bachelor’s degree or higher. There’s also a pattern linking community college graduates, middle-wage jobs, and upward mobility: The top five states for associate degrees—Wisconsin, Minnesota, Iowa, South Dakota, and North Dakota—also stand out for their high concentration of middle-wage jobs and upward mobility. In our ongoing research, we will aim to understand how these states achieved robust community college outcomes, and what role the public and higher education systems have played in support of upward mobility.

Second, the mostly small and rural regions that stand out for their middle-wage jobs and upward mobility also have a strong stock of social capital, even when compared to other places of the same size. The social capital measure we use includes indicators such as voter turnout, return of census forms, and participation in community organizations. Prior research has offered a number of explanations for the relatively high and persistent social capital of these regions, including a pattern of long-term residence and strong attachment to place. Our finding is also consistent with past work that’s linked high social capital with strong economic outcomes.

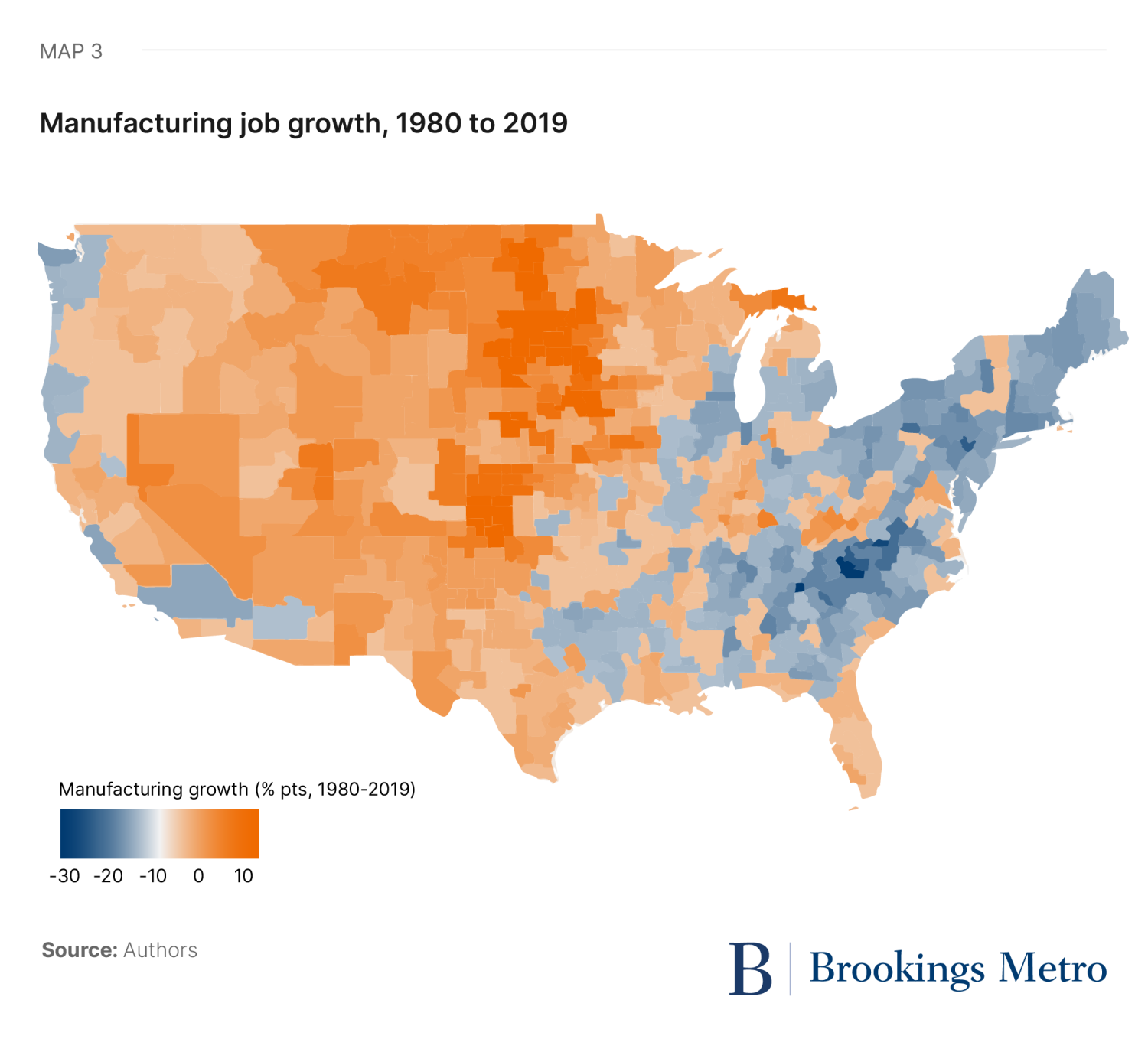

Third, and most importantly for policy, these regions are more likely to have a higher share of manufacturing jobs than their peers—and manufacturing in these regions is more likely to have grown over time. A “middle model” of economic development, it seems, benefits from both the infrastructure to develop skills as well as the infrastructure to support good manufacturing jobs.

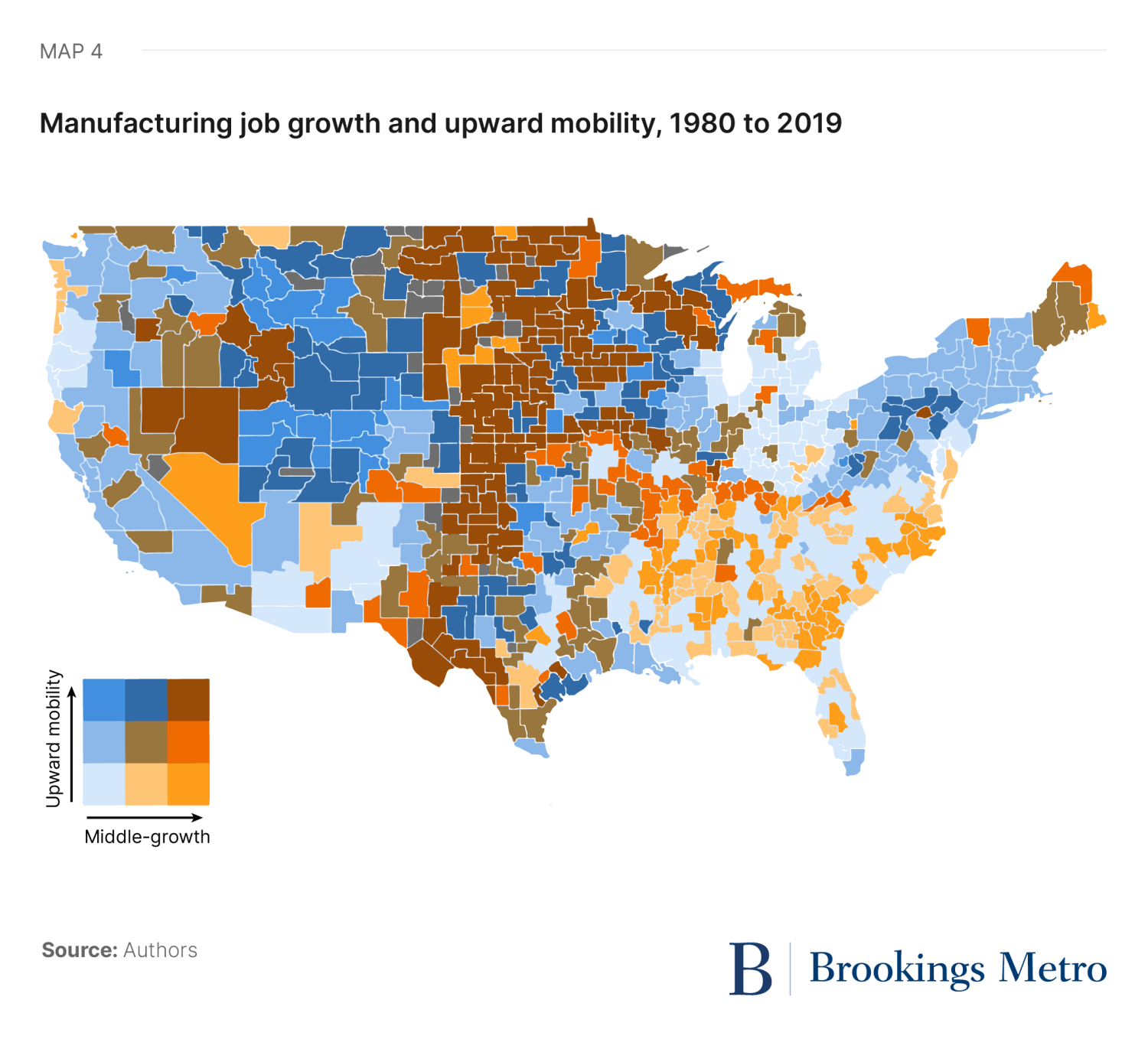

Map 3 shows U.S. manufacturing growth since 1980 has concentrated along the central corridor, closely aligned with the growth of middle-wage jobs and upward mobility during the same period. There is a strong association between areas where manufacturing is growing and places where middle-wage job growth has been strongest. This is perhaps unsurprising, because manufacturing jobs are predominantly middle-wage jobs.

What is most encouraging about these data for manufacturing advocates is that strong manufacturing regions during this period were also the regions with strong upward mobility (see Map 4). This is good news, particularly given the projected 200% increase in manufacturing investment over the coming years based on factory construction data. It is worth noting that there is a lack of manufacturing growth and upward mobility in the Rust Belt and Southeast region of the country—places that have been hit particularly hard by foreign competition and the “China shock.”

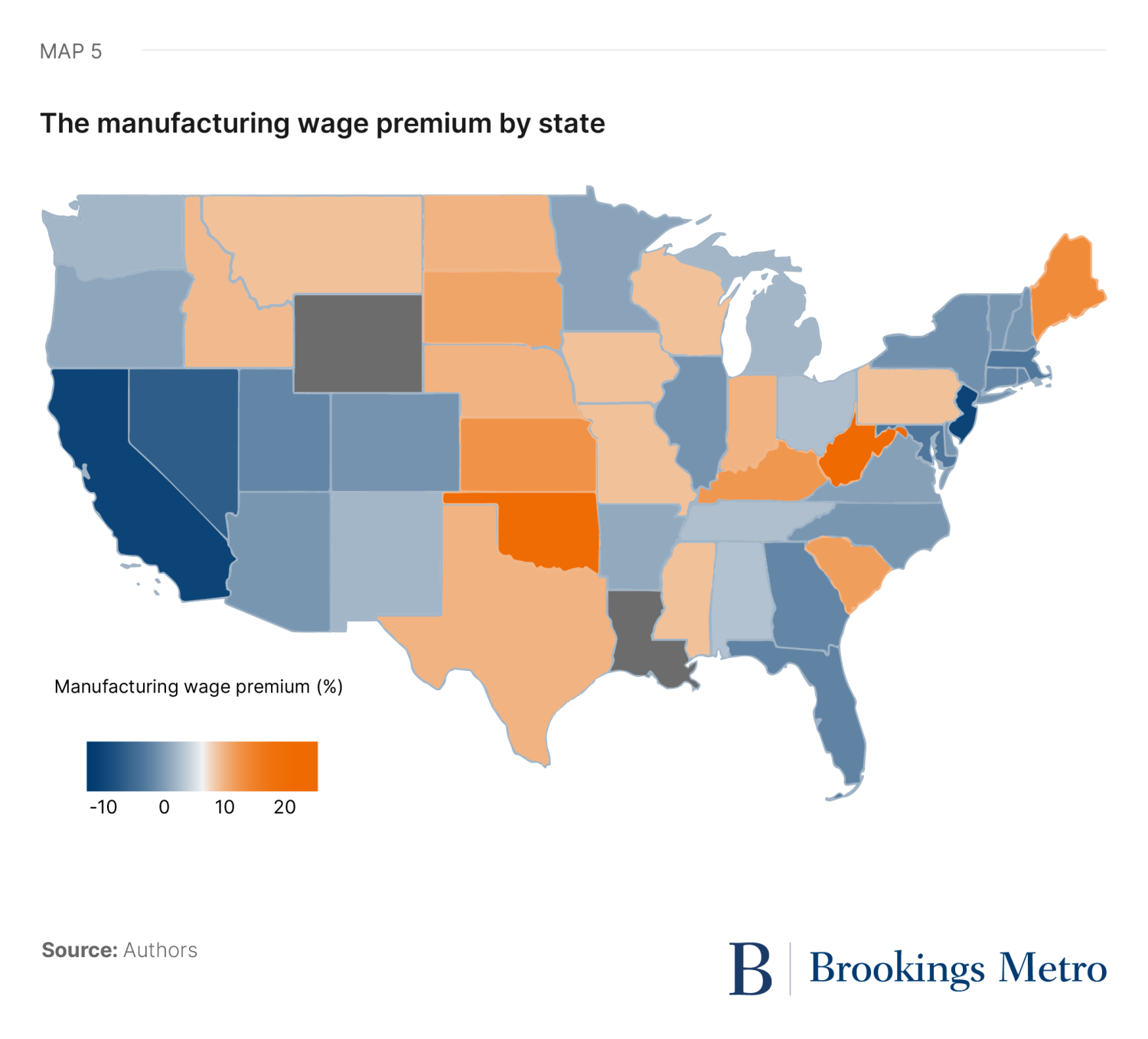

It is important to recognize that not all manufacturing jobs are middle- and high-wage jobs. Indeed, the “wage premium” associated with manufacturing work has declined since the 1960s. By 2019, workers without a four-year degree in manufacturing careers earned a median wage that was comparable to the wage they could have earned in non-manufacturing industries. However, the quality of manufacturing jobs varies significantly across the United States (in general, these jobs still offer a weekly earnings premium). Map 5 shows how the wage premium for manufacturing remains high in states with strong upward mobility and growth in the middle of the labor market.

As policymakers across the country continue to search for economic approaches that work for the heartland, we can learn something from these places and how they have stabilized employment and increased wages and mobility. They can serve as models for the hundreds of midsized cities in the middle of the country that have the potential to grow middle-wage jobs and increase upward mobility.

These economies are not necessarily going to benefit from programs that are creating “tech hubs” or “innovation engines” in the mold of Silicon Valley. Instead, these places can benefit from the broader effort represented in federal legislation such as the CHIPS and Science Act and Inflation Reduction Act to invest in the country’s industrial base—the semiconductor, energy, and defense industries in particular—and strengthen domestic supply chains. As these policies are implemented, one measure of their success will be how well they expand middle-wage jobs and improve upward mobility in the regions that host this industrial expansion.

Now is the time to adopt a new approach to rebuilding the middle class—and the middle of the country. Places such as Fergus Falls, Minn., Grand Forks, N.D., and Manhattan, Kan. show us there’s a path for struggling regions to achieve wage growth and upward mobility. With a focus on K-12 and postsecondary education as well as rebuilding the industrial economy, these regions can expand on a model of economic vitality that’s made for the heartland.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Ben Armstrong is executive director of the MIT Industrial Performance Center and co-leads MIT’s Work of the Future initiative. Elisabeth Reynolds is a professor of practice in MIT’s Department of Urban Studies and Planning and Former Special Assistant to the President for Manufacturing and Economic Development at the National Economic Council.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).