This piece is lightly adapted from the author’s Jan. 14, 2026, address to the European Parliament’s convening in celebration of the tenth anniversary of the EU’s Open Internet Rules and their applicability to the AI era.

The global market for artificial intelligence is taking shape at breathtaking speed—and with remarkably few constraints. Vast new data centers are being financed as if they were shopping centers. Foundation models are being treated as if they are the next “Intel Inside.” And the firms that used their control of computing power, data, and distribution to become Big Tech are relying on those same resources to control the tools of artificial intelligence, become Big AI, and dominate its downstream applications.

This should concern everyone who believes innovation comes from competition, not control.

AI is not merely another technology cycle. It is an infrastructure transformation that is as consequential as the printing press, as economy-shaping as electrification, and as society-reordering as the networked internet. Yet unlike earlier transformations, the AI era is developing at a moment when digital market power is already highly concentrated. The same companies that shaped the online platform era now sit at the center of AI.

The question for policymakers globally is therefore not simply how to regulate AI risk, but whether market bottlenecks will be allowed to determine who gets to innovate, compete, and participate in the AI economy.

It is the defining issue of the intelligence era.

A familiar pattern: Openness as a ladder, control as a strategy

The story is a familiar one—and it should make us wary.

During the rise of the internet economy, today’s major online platforms championed openness. Nondiscriminatory access to internet standards meant that anyone with an idea could launch a new product. Because those products needed to reach consumers, many companies championed open access to broadband networks.

Once those companies grew into dominance, however, they began to behave in ways that contradicted the openness values that enabled their growth. They used openness as a ladder for themselves, and then pulled it up behind them.

Through scale and strategic behavior, they learned to control data, distribution, and markets. Their systems became more closed. Competition narrowed. Switching costs grew. And the public increasingly absorbed the downsides of privacy erosion, misinformation, and child safety harms as the companies externalized risk off their balance sheets and on to the backs of the public.

Now those same firms are leading the development of AI, and they are importing the same pull-up-the-ladder, competition-foreclosing strategies that worked so effectively in the online platform era.

Why this matters: AI concentrates power—unless we choose otherwise

AI is commonly discussed as if it is mainly about “ever bigger models.” Such foundation models matter because they supply the power necessary for the practical application of AI—and the AI future will depend on applications.

In this regard, history teaches us an important lesson. Technology-driven transformation is less about the primary technology itself than its second-order effects that enable new uses, new processes, and new ways of working.

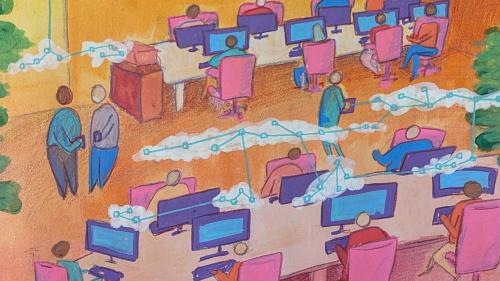

The AI economy is an application economy—just like the tech revolutions that preceded it. If the goal is productivity growth, scientific discovery, improved public services, better education, better health care, and broader economic opportunity, then success depends on the diffusion of AI applications through widespread adoption and broad-based innovation.

That diffusion will not happen if a handful of companies control bottlenecks to the capabilities necessary for AI. At the heart of needed AI policy, therefore, is a simple oversight principle: Prevent bottlenecks and promote diffusion.

Three chokepoints that will decide the AI era

The diffusion of AI applications requires openness in three critical chokepoints.

Data: The fuel of intelligence

Data is the raw material of AI.

Scaling the capabilities of AI models requires both volume and diversity of data. If access to this essential input becomes restricted—through proprietary formats, lack of interoperability, or exclusionary licensing—competition inevitably stalls.

That is why the AI era requires what the open internet era understood: Nondiscriminatory access to essential inputs for innovation and growth. Without data portability, interoperability, and shared access, the AI ecosystem will calcify around a small group of entrenched incumbents who control the essential asset.

Compute: The engine and the moat

If data is fuel, computing power is the engine.

Today, roughly two-thirds of the world’s cloud computing capability is controlled by three companies, each racing to dominate AI. These companies are committing trillions to the construction of massive new data centers, justified by the need to “scale” toward ever more capable systems. McKinsey estimates that over $5 trillion could be spent globally on AI data centers by 2030.

This investment is often described as innovation. The quest for the human-like capabilities of artificial general intelligence (AGI), many argue, is tied to the ability to scale to ever greater computing power. Others point to the diminishing returns of scaling and the need for breakthroughs beyond raw compute.

Policymakers must then ask the harder question: Are these investments accelerating capability or establishing the ultimate bottleneck?

Computing power begins as a technical advantage, but it quickly becomes a strategic moat of preferential access, bundling, long-term tie-ins, opaque pricing, and closed ecosystems. These dynamics are hard to observe but easy to weaponize. Once a company becomes a gatekeeper to computing power, it can determine whose models compete, whose startups scale, and whose innovations reach the public.

Models: The final bottleneck

Finally, the models themselves.

The dominant foundation models remain overwhelmingly closed. Despite open models often being cheaper and increasingly comparable in performance, researchers at MIT and Georgia Tech found that closed models capture approximately 80% of usage and 96% of revenue.

Why? Because closed model providers lock in developers. Applications become dependent on proprietary capabilities. Switching becomes costly, risky, and operationally difficult. What begins as a technical choice becomes an economic dependency.

At the center of this control sits the application programming interface (API) through which computer programs interoperate. APIs do more than connect applications to models. They define what applications can do, how they evolve, and what innovations are possible. When OpenAI, for instance, changed GPT-3.5 endpoints, hundreds of dependent applications faced costly migrations.

By controlling their APIs, owners of closed AI models can effectively govern the evolution of AI itself. API control lets them steer innovation toward their own interests, shape the marketplace in their favor, and limit competitive threats.

The result of such behavior is predictable: Innovation is suppressed, costs rise, risk concentrates, and diffusion slows.

The real prize is not models themselves, but what models enable

AI will not transform economies because a few firms train large models.

Transformation will come from what those models enable: specialized applications across every sector—manufacturing, logistics, energy, medicine, education, defense, journalism, government services, and more. That is where productivity grows, discovery begins, and opportunity expands.

However, that transformation cannot fully occur if a handful of firms control the essential components of the AI stack and see their future as creating a toll booth to control dominance of the application layer.

Openness and competition are essential to application growth

A competitive market of application developers is essential. The lesson of the last several decades teaches that innovation flourishes when power has guardrails and opportunity is diffused. The lesson of AI will be no different.

We have evolved from an open internet to the necessity of open intelligence, and because AI is inherently transnational—data flows, compute markets, models, and applications all operate across borders—no nation can fully solve this alone. Compatible oversight across democratic systems will matter more than rigid conformity. What is needed is not identical regulations, but compatible approaches that establish mechanisms for regulatory cooperation, data governance, and shared principles that allow innovation to flourish within guardrails.

In this regard, the “my way or retribution” strategy of the Trump administration—the equivalent of 21st century digital mercantilism—ultimately hurts the nation and the companies it purports to protect by thwarting innovation-driving competition. To compete internationally, there must first be vibrant competition at home.

The question before policymakers is simple, but urgent: Will we allow bottlenecks to determine the future of AI—or will we design AI policy to expand participation, competition, and diffusion?

AI can become the greatest engine of productivity since electrification, but only if we prevent bottlenecks before they harden into gatekeepers. Rather than a choice between innovation and oversight, this is a choice between open intelligence and privately governed intelligence. If we wait until dominance is complete, the debate will be over—not because the public decided, but because the powerful already did.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

From open internet to open intelligence: Why AI’s market structure matters more than ever

January 21, 2026