Between 2021 and 2022, the 117th Congress passed a series of laws totaling nearly $3.8 trillion: the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA), Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), CHIPS and Science Act (CHIPS), and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). These pieces of legislation authorized $80 billion in “place-based industrial policy,” designed to encourage inclusive economic transformation—a shift toward a more innovative, prosperous, and resilient economy, and from lower-productivity to higher-productivity activities—through targeted investments in key industries and leveraging clusters of talent and innovation in specific places to spur development (see text box: What is place-based industrial policy, and why does it matter for US regions?). More broadly, this economic transformation was aimed at advancing bipartisan national objectives of national security and competitiveness by strengthening technological innovation, economic mobility and resilience, and broad-based growth.

What is place-based industrial policy, and why does it matter for US regions?

Place-based industrial policy refers to public investments that aim to accelerate innovation, job creation, and long-term economic growth by focusing on the unique assets of specific geographic regions. While “industrial policy” broadly means supporting key sectors to drive economic transformation, “place-based industrial policy” ensures that those interventions are rooted in local context, leveraging regional strengths and addressing regional gaps to meet national goals.

Place-based industrial policy is a response to growing divides and “winner-take-most” dynamics in technology-driven sectors. Between 2005 and 2017, just five “superstar” regions accounted for over 90% of the nation’s innovation sector growth, and have benefited accordingly from the creation of higher-paying jobs and other measures of prosperity. And within regions, unequal exposure and access to tech-related career pathways have excluded Black, Latino or Hispanic, rural, and other disadvantaged groups from these sectors. These trends illustrate not only an inclusion challenge, but a competitive one: The nation cannot achieve its fullest potential without activating all its regions and communities.

Transformation, then, refers to regions reversing the trend of “superstar” dominance. It means all regions—not just on the coasts, but across the country—have an opportunity to secure a foothold in an innovation-driven, high-growth sector, benefiting all its workers and families. Importantly, place-based industrial policy is designed to not only spur regional clusters, but also fundamentally transform how they operate, so regional leaders move away from historical silos of economic, workforce, and community development and instead work together to advance a shared vision for regional economic transformation. This makes place-based industrial policy not just a funding opportunity, but a test of regions’ civic capabilities and a down payment on a more inclusive and resilient economic future.

These investments were notable for their size and focus on both critical sectors and distinctive regional assets. Yet even before the 2024 election, it was clear that the wave of federal investments through ARPA, IIJA, CHIPS, and IRA (which fell short of their potential due to significant shortfalls in congressional appropriations) would not be sufficient on its own to transform regional economies. By the end of 2024, more than $41 billion had been deployed for place-based industrial policy, but these resources are now being stretched thin among dozens of metropolitan areas, across five years or more, spanning thousands of organizational partners, and with a large share of overall funding dedicated to a relatively small number of semiconductor projects.

These goals were particularly evident in a series of competitive grant programs authorized in ARPA and CHIPS and available to cross-sector regional coalitions—groups of civic, community, business, workforce, and research organizations and institutions in a metropolitan area working together toward shared economic objectives (Table 1).

Today, the threat to the long-term impact of these investments continues to rise, given the Trump administration’s interest in dismantling executive agencies, new and long-standing programs, and regulations (in some cases even looking to claw back grant funds). In response, state and local public and private sector funders who have contributed to these efforts are now understandably feeling the need to shore up organizations and programs affected by federal retrenchment across many domains. The prospects for a trade war pose additional challenges for regional economies.

What could prove transformative with sufficient attention, however, is the collaborative “muscle” that regions built in this period: the coalitions that regions built and advanced around a shared vision for inclusive growth, and the capabilities they strengthened to deliver on it. These capabilities include orienting local government, nonprofit, business, and other stakeholders to a shared strategy; activating the private sector to inform and engage in these efforts; and mobilizing resources through sustainable financial models to maintain momentum. Philanthropic and economic development organizations—often working together—played especially important roles in this work, stepping in to identify opportunities, coordinate partners, build delivery infrastructure, and serve as strategic intermediaries. Leaders in state and local government and business have benefitted enormously from philanthropy’s active and flexible engagement, as this report will illustrate.

This report examines five regions with diverse civic and economic characteristics, where philanthropy played an integral role by deeply understanding their region’s capacity, strengths, and gaps, and then deploying capital, building relationships, exerting influence across sectors, and lending operational support as needed, with the goal of leveraging federal funding as a catalyst for economic transformation.

Importantly, this multisector civic infrastructure matters for regions well beyond the last few years of significant federal investment. Evidence suggests that such networks help regions become more resilient and prepared to seize opportunities in the face of shocks. The past 20 years alone have delivered a series of economic shocks, from the Great Recession to COVID-19; policy shocks, from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act in 2009 to the recent federal funding surge; and an increasing wave of environmental shocks in the form of extreme weather that is devastating communities, producing record losses, and threatening local economies. And now, the risk of federal retrenchment, intensive protectionism, and major tariff increases raise new challenges for regions. This report identifies lessons about the capabilities required and how regional leaders can build and sustain them to forge more resilient, prosperous economies.

Case study regions

How they were selected

The case study regions were selected to examine efforts to attract, mediate, and sustain the impact of new federal investments between 2021 and 2023. In each case, we identified places that used both the application process and the resulting investments not only to launch impactful programs, but also to strengthen the core functions needed for economic transformation. In order to get a broad view, we looked at regions that vary in size, location, capacity, and degree of alignment of economic and workforce development systems, in the hopes of offering insights and lessons that can apply across a broad range of regional contexts.

Chicago/Illinois: Innovate Illinois

In response to early missed opportunities for federal funding, state, university, industry, and philanthropic leaders partnered to launch Innovate Illinois—a collaborative, statewide effort to assemble the most investable opportunities to drive innovative, inclusive growth. Foundations provided flexible capital and leveraged their influence to align leaders across government, universities, business, and nonprofit sectors behind the most promising proposals, and support community engagement in design and implementation. The result included multiple Tech Hubs designations, one of which led to a $51 million federal award and another that helped make the case for $500 million in state investment.

Fresno, California: F3 Coalition

The Fresno-based Central Valley Community Foundation (CVCF) leveraged a regional economic initiative, Fresno DRIVE, into a $65 million BBBRC award to help the region address technological disruption and the growing impact of climate change on its most critical sector: agriculture. Leveraging credibility and influence with a range of stakeholders, CVCF was able to bridge fragmented sectors and institutions to support the Fresno-Merced Future of Food (F3) Coalition and secure additional state funding to launch F3 Innovate to sustain the work in the long term. CVCF played a hands-on role in building relationships by fostering trust and enabling collaboration among diverse organizations and constituencies, aligning their efforts into a coordinated, integrated approach to implementation and future investment.

New Orleans: Sector partnerships

Recognizing workforce challenges in some of the region’s most important industries, leaders in New Orleans leveraged federal funding to support employer leadership in strengthening talent development systems (including high schools, community colleges, specialized training academies, and industry and economic development associations) that better prepare students, trainees, and job seekers for in-demand roles, and also support them through preparation, job attainment, and career mobility. Despite not winning a Good Jobs Challenge grant to advance this work, the Greater New Orleans Foundation (GNOF) and economic development, industry, and community partners leveraged flexible ARPA funding from the city of New Orleans and rallied behind a new, rigorous sector partnership model in construction and green infrastructure, health care, transportation and logistics, and advanced manufacturing. GNOF is not only layering public and private capital to catalyze and sustain this effort, but also providing direct operational support by staffing and providing technical assistance to implementation partners. Businesses in each sector have committed to collaborating to broaden talent pipelines to meet future talent needs, while expanding opportunities for residents.

Syracuse, New York: CHIPS impact

Following the signing of the CHIPS and Science Act, the state of New York created “Green CHIPS” incentives to complement federal incentives and add sustainability and inclusion criteria. This pair of policies yielded Micron’s $100 billion investment in semiconductor “fab” facilities in Syracuse. The state endowed regional intermediary CenterState CEO—a business-led, nonprofit economic development entity—with considerable resources and authority to negotiate with Micron and design what will be a largely state-funded strategy for workforce and supply chain development. Now, the challenge is to ensure that the benefits of this investment reach as deeply into the community as possible. This will require a deep and novel partnership between CenterState CEO and philanthropies, especially the Central New York Community Foundation, which will play an important role in securing and deploying over $150 million in capital for education, workforce development, housing, and other community priorities, including providing operational support to build the capacity of nonprofit organizations to effectively and sustainably scale their impact to meet the new opportunity.

Tulsa, Oklahoma: Tulsa Innovation Labs

The George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF), an affiliate of the Tulsa Community Foundation, launched Tulsa Innovation Labs (TIL) to make big bets to advance tech-driven economic growth in a region known for its legacy energy and aerospace industries. TIL emerged as a nimble, evidence-driven, collaborative leader in the region’s successful bids for $90 million in federal awards to build out Tulsa’s advanced aerial mobility cluster. TIL now manages multi-partner implementation and leverages corporate capital—through initiatives such as Rose Rock Bridge, a philanthropically supported venture studio for energy startups—to strengthen innovation infrastructure in the long term.

A stress test of regional readiness

The unprecedented flood of federal investments was a welcome and overdue measure of support for cities and regions. Most were struggling to retain their advantages—or even find a foothold—in the industries of the future in ways that would allow more people to both contribute to and benefit from economic growth. But in some ways, it was a “dog that caught the car” moment, as places suddenly found themselves with access to substantial resources to design and advance inclusive growth plans, but not the civic infrastructure, cross-sector coordination, or implementation capacity required to absorb, deploy, and sustain those investments effectively.

Regions are not unaccustomed to economic strategy processes, but a large share of the federal funding that touches regions has traditionally been designed and delivered in a place-agnostic way. Since 1998, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) has required regions to create Comprehensive Economic Development Strategies in order to receive funding. But the lion’s share of federal funding for places has traditionally been determined by formula (such as the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant and the Department of Transportation’s Highway Trust Fund), awarded on a project-by-project basis (the Department of Transportation’s RAISE grants or the National Telecommunications and Information Administration’s broadband grants), and often managed by some combination of state and municipal governments and nonprofits (as with most federal workforce funding through the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act).

But the competitive federal grant opportunities required regions to do something substantially different: bring together a broader-than-usual coalition around a more specific-than-usual strategy. Many places have civic partnerships aimed at creating more inclusive talent pathways, university partnerships aimed at commercializing technology, and/or public-private partnerships aimed at neighborhood revitalization. These efforts often remain siloed yet fairly broad—agnostic of industry sectors, occupations, and other factors that matter greatly for generating economic growth and opportunity. But recent coalition-based federal funding opportunities, such as Tech Hubs and the BBBRC, have required regional leaders to gather broad coalitions of industry, university, nonprofit, government, philanthropic, and other regional stakeholders around specific, precise, evidence-based strategies for regional economic transformation.

The work of organizing a broad coalition around a specific strategy was challenged by the way in which federal resources were deployed through new funding streams and mechanisms—from coalition-based grants and loans to tax credits and incentives—that were designed in silos in Washington, D.C., each with unique time horizons, objectives, and funding criteria, and fragmented across departments and agencies. This left regional leaders with the difficult task of aligning potentially complementary programs; for example, “stacking” innovation, talent, and infrastructure investments. Funding from state governments tends to be fragmented in the same ways. Layering these theoretically complementary but practically incompatible funding sources to fuel a specific sector-focused strategy was a major test of regional capacity.

Finally, a large share of funding was dedicated to delivering programs or subsidizing specific private investment (particularly in the case of CHIPS), as opposed to investing in governance or the collaborative capacity to coordinate multi-sector, multi-stakeholder coalitions responsible for delivering sustained and inclusive growth. This highly categorical, restricted-use approach to funding has long been common in government funding. It’s typically intended to minimize waste and fraud, as well as the use of funds in ways that stray from legislative intent. (It is common in philanthropic funding as well, as a means of focusing limited resources on well-defined program priorities.) While some government investment programs allowed for or encouraged funding to be directed toward governance, this tended to be a very small share of spending, even as the demands of these programs were straining the capacity of local organizations and coalitions.

Thus, many regions were on their own in attempting to integrate newly funded programs with existing ecosystems, initiatives, and resources, despite the significantly increased level of complexity involved in holding together these coalitions and maintaining fidelity to strategy. Absent dedicated new funding for this coordinating work, regional leaders had to build new regional capabilities and institutional capacity across multiple existing, emerging, and new entities, re-allocating or pulling in new local funds to do so—all while actively delivering workforce and entrepreneurship programs, building new physical infrastructure, and executing an array of other projects in their portfolios.

The challenge of transforming regional economies

There is no shortage of commentary on the economic growth and inclusion challenges affecting most regions across the country, particularly those left behind in the initial wave of technology-driven advanced industry growth that concentrated in coastal superstar cities.1 And yet, it is often underestimated just how difficult it is for regions to establish a meaningful foothold in these sectors. New York state, for instance, invested over $20 billion in one semiconductor research and development facility, plus billions more in incentives to attract semiconductor firms over the several decades leading up to Micron’s $100 billion investment in Syracuse. Other frequently cited success stories such as Austin, Texas and Raleigh-Durham, N.C. also have underrecognized histories of state and federal investment. All regions, but especially those without such resources, need to relentlessly align their resources to focus on a particular niche where they have a competitive advantage, as Fresno has done with agricultural technology, Tulsa with advanced aerial mobility, Syracuse with semiconductors, and so on, as explored in the case studies. They cannot afford to waste a single dollar or day on duplicative or misaligned efforts.

The challenge is that regional economic and workforce systems—and the increasingly diverse arrays of independent organizations that comprise them—are not built nor incentivized to advance coordinated efforts. Most regions are home to some combination of: “promotion-focused” organizations, usually assessed on shorter-term metrics such as job and population growth (e.g., economic development entities focused on business attraction); “inclusion-focused” organizations, such as those funded to deliver job training or revitalize neighborhoods and commercial districts, but agnostic about industries, occupation types, and other economic drivers (e.g., community-based organizations with workforce development programs); and “innovation-focused” organizations, with a mandate to drive research and development but generally agnostic of which communities they serve (e.g., tech incubators and accelerators). It is exceedingly rare to find any single organization—or a regional coalition of cross-sector partners—that is focused on generating long-term, inclusive growth in innovation-based sectors.

The point is that transformative economic development requires more than coordination among organizations that generally have similar incentives. It also requires coordination across organizations with different—and potentially competing—priorities, incentives, and understandings of the economy. This is a challenge that cannot be solved through top-down, command-and-control planning. Despite the appeal of centralization in terms of speed and decisiveness, no one organization has the data to assess what is happening within emerging sectors, what is occurring within programs meant to grow those sectors or create pathways into them, and what is happening in communities that prevents people from accessing those pathways. (Importantly, no single organization could have this data, because it does not exist; relevant insights need to be gathered via consistent, trust-based interactions with firms and people.) But the point is not limited to data: Authority, capacity, and resources are all distributed, not centralized. Thus, the need for distinctive, robust capabilities that address that reality in each region.

Five capabilities for regional economic transformation

Across the country, most regions still lack what they really need to transform: an inclusive and strong economic strategy development and implementation “muscle” that can integrate input from a broad range of actors about economic priorities, assets, and gaps, but also set a clear direction and get organizations to stay on that path. Achieving this, our analysis shows, requires five distinct, regional capabilities:

- Connect networks and build trust among increasingly disconnected economic actors, including business leaders, community organizations, students, and entrepreneurs.

- Orient regional stakeholders toward a shared understanding of the economy and the pathways to inclusive growth.

- Activate key private sector leaders to inform and engage in strategic regional inclusive growth efforts.

- Integrate teams of diverse, complementary organizations to solve specific, high-priority challenges using evidence-based interventions.

- Mobilize resources through sustainable financial models to maintain momentum, using performance measurement tools to identify the highest-priority areas for investment.

There are a range of ways to structure and deliver these core capabilities, from more centralized to more distributed models, perhaps involving up to 10 “lead” organizations in larger regions. They cannot be, and should not be, contained within a single organization. The traits that make an organization an effective connector—for example, being widely trusted as a neutral intermediary—tend to make an organization an ineffective integrator. At the same time, however, each capability requires substantial insight from and influence over businesses—and in most regions, only one or two organizations have the requisite connections to and credibility with businesses. In practice, therefore, these capabilities tend to imply a significant role for one or two business-led (or at least heavily business-oriented) organizations of the type that are profiled in this report’s case studies.

A key hypothesis we explore in these case studies is that a semi-formal “dyad” relationship—between a business-oriented organization and at least one regional philanthropy offering a complementary perspective and toolkit—provides a strong foundation for building these regional capabilities to drive economic transformation.

Philanthropy’s role in strengthening regional capabilities

In philanthropy-business dyads, funders often play a catalytic role, helping to clarify regional needs and strengths while engaging business-oriented organizations as essential co-pilots whose credibility, networks, and market insight are critical to activating leadership, shaping strategy, and sustaining alignment over time.

For example, philanthropies often have deep relationships with community-based organizations that provide an important perspective on inclusive growth and represent important interests. Engaging with those perspectives and interests is too often perfunctory or overlooked in regional economic development efforts. Funders can act as a neutral party to enable collaboration when compared to other stakeholders who find themselves competing for funding, relationships, or influence. And of course, they have flexible resources that can be deployed more quickly and with less process than most public or many private funds—bringing historically excluded voices into economic strategy design or providing risk capital to prove the social and economic return on investment of a new model, for example.

The case studies illustrate how philanthropy has enabled the creation or reimagination of institutions that blend strategic and operational functions (a “player-coach” model). These nimble approaches allowed strategy to move to implementation at the speed of the economy (and aggressive grant timelines), keeping the focus on “what needs to get done” rather than stymied by questions of “who does what.” Bringing the convening organization into the delivery process enables that organization to understand the intricacies and shifting needs of program delivery. It also enhances fidelity to strategy across a collaborative effort, because the strategist/convening organization can spot deviation more quickly and bring capacity to support or supplant underperforming entities or efforts.

These are innovative and emergent institutional arrangements, the origins and mechanics of which must be much better understood by regional leaders and federal decisionmakers interested in advancing regional prosperity. Philanthropy and economic development typically operate adjacently—addressing complementary but separate issues—and are now integrating to co-own inclusive growth goals, and often focused on emerging industries that are not the focus of philanthropic efforts (and may be mysterious or novel to many economic and workforce development actors, for that matter). The case studies, some of which focus more on philanthropies and others more on the organizations that philanthropy sought to influence, therefore offer valuable lessons for other regions seeking models tailored to their own contexts.

The case studies document how philanthropies came to recognize the need to engage more directly in economic development. In some cases, this was spurred by the realization that their work in other areas—including K-12 education, the racial wealth gap, workforce development, and child care—are downstream of the structure of the economy. Even the most effective programs in these domains struggle to achieve lasting impact if the regional economy does not provide enough good jobs, wealth-building opportunities, inclusive growth, and the tax revenue that results from economic expansion. In other cases, philanthropies got involved because it was clear even without a pre-existing theory of inclusive growth that more effective economic and workforce development systems were required to attract and deliver new federally funded initiatives.

A process for aligning philanthropic tools to regional priorities

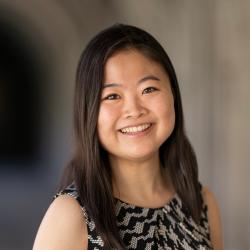

In each of these regions, with varying degrees of intention and formality, philanthropies identified gaps in regional capabilities, including those that were either missing or underdeveloped, such as the often-overlooked attention required to address racial, ethnic, and gender inclusion.

In doing so, philanthropies intentionally assessed their own strengths and weaknesses across this spectrum of capabilities, embracing their potential to directly take on key capabilities that are needed either temporarily or long term, depending on their structure and mission, or to use funding and other tools to fill gaps (see Figure 1). This report and the accompanying case studies provide a range of examples of how funders closed gaps and enhanced key capabilities.

Funders profiled here used a range of traditional as well as novel tools, including some recently surveyed by the Aspen Institute. These tools fall into four main categories:

- Capital: Providing flexible financial resources, such as grants or program-related investments, to incentivize partnerships and support initiatives aligned with inclusive growth strategies.

- Relationships: Cultivating and strengthening networks, especially with community-based organizations and other local stakeholders, to foster trust and effective collaboration.

- Influence: Using their credibility and visibility to shape the regional agenda, align public and private priorities, and catalyze additional investment.

- Operational support: Applying specialized knowledge, resources, and skills such as grantmaking, evaluation expertise, and flexible staffing to enable and sustain effective cross-sector coordination.

In deploying these tools, the philanthropic funders we analyzed typically aimed at enhancing the capabilities of the inclusive growth system (capabilities that are best shared by more than one organization) rather than primarily focusing on building the capacities of individual organizations. The following section describes these capabilities and the ways in which funders strengthened them.

Building and activating regional capabilities

Connect networks

It is well established that social capital has a profound impact on inclusive growth, including “bonding” capital that connects similar actors (such as entrepreneurs or workers with similar backgrounds) and “bridging” capital that spans socioeconomic, racial, or other divides (such as between CEOs and leaders of community organizations). Decades of research by Robert Putnam, Raj Chetty, and others have demonstrated this in powerful ways.

The formation of social capital, especially of the bridging variety, has not typically been understood as a core function of regional economic development, though an earlier generation of research—for example, on developing effective workforce development networks in local labor markets—did underline its value and relevance. That understanding, however, must change for several reasons. First, growing polarization and declining trust in institutions are inhibiting collective action of any sort. Second, achieving inclusive growth requires working alongside organizations that aren’t often involved in strategy development but can inform and co-create interventions (providing insights about the assets and structural barriers in historically excluded communities), and then implement them (for example, providing intensive outreach or tailored supports that enable disadvantaged students to enroll in and complete high-demand certificate programs). And third, breakthrough innovations—especially of the sort that struggling regions desperately need—often emerge from unusual combinations of expertise that occur when people from distant disciplines are brought into close contact.

To effectively leverage an influx of funding, sector-focused economic development efforts must include a regional capability to consistently bring together unexpected combinations of people and organizations. These interactions are essential to building trust and sharing real, ground-level information. While they should be guided by a clear sense of which economic actors are disconnected and need to be connected, they need not be immediately oriented around specific tasks or goals. Our case analyses suggest that when interactions are framed too narrowly (focused on informing a strategy or advancing an agenda), they tend to become transactional and fail to establish the trust needed for long-term collaboration. The kinds of relationships that need to be (re)built require space for spontaneity and familiarity to take root—conditions that are difficult to create when every conversation is in service of some other objective. The relationship-building interactions lay the groundwork for more productive, goal-oriented work down the line, including the hard conversations and decisions about priorities and resource allocation.

In Fresno, Calif., the Central Valley Community Foundation (CVCF) played a catalytic role in building the connective tissue required for economic transformation. Beginning in 2017, under the new leadership of former Fresno Mayor Ashley Swearengin, CVCF invested in relationships and brought together stakeholders who had historically worked in isolation or even in conflict, including farmworker advocates, agricultural industry leaders, university researchers, and local and state government officials. This work laid the foundation for Fresno DRIVE, a collaborative 10-year, $4 billion planning effort that convened over 300 participants across sectors to craft a shared vision for inclusive development.

Through this work, CVCF helped bridge institutional and cultural divides that had long hampered regional collaboration. The relationships and trust cultivated during the DRIVE process weren’t just instrumental, they were durable—providing a critical foundation of trust and buy-in across diverse regional stakeholders. When the EDA announced the BBBRC grant program in 2021, CVCF leveraged this capacity to help form the Fresno-Merced Future of Food (F3) Coalition—a cross-sector alliance that secured a $65.1 million federal award, which was the largest EDA award to any region in the country.

What distinguished CVCF’s approach and set it up for future success was its ability to use its influence and relationships to connect actors who rarely sat at the same table: farmworkers and environmentalists, public agencies and private firms, grassroots organizations and major universities. CVCF built the credibility required to bridge divides, identify shared interests, and model a collaborative ethic that has characterized the region’s early implementation of the BBBRC-funded initiative. In the accompanying case study, we explore how that worked and what choices were critical when.

In Chicago and across Illinois, as public, private, and university stakeholders were preparing applications for funding amid the early rounds of competitive federal funding opportunities in 2021, philanthropic leaders wanted to ensure that historically excluded communities would be involved in shaping the state’s tech-based economic future, in alignment with federal guidance for regions to develop inclusive strategies. Thus, Builders Vision, the Chicago Community Trust, the Joyce Foundation, the MacArthur Foundation, and the Pritzker Traubert Foundation all supported a new effort—dubbed Innovate Illinois—both to improve the state’s chances of receiving significant investment and to use influence and flexible capital to bring community voices into the process. As a key example, philanthropic leaders used their influence and capital to encourage Innovate Illinois leaders to enlist the United Way of Metro Chicago’s (UWMC) Neighborhood Networks to bridge the gap between high-level regional strategy and neighborhood-level needs, ensuring that community voices informed decisions about workforce development, place-based development, and equity goals. To date, Innovate Illinois leaders have shared relevant funding opportunities with UWMC and used philanthropic capital to provide flexible capacity to support federal grant proposal submissions.

Note, however, that UWMC’s involvement is still an early step toward connecting networks. As emphasized earlier, it is important for this connect capability—in its fullest form—to exist outside of structured, time-limited strategic initiatives, and to instead be sustained long term, beyond any single initiative. Innovate Illinois and UWMC’s partnership has provided a beginning, but it will take intentional, ongoing, and authentic network-building work to build trusted relationships and collaboration across the region to sustain inclusive growth.

Orient regional stakeholders

Resource-constrained regions that are trying to establish a durable niche in advanced industries do not have enough federal, state, or philanthropic money to support all workforce and economic development initiatives across all industry sectors. Rather, they need a critical mass of organizations to be relentlessly focused—for a decade or more—on key industries, occupations, and geographies, and be convinced that their interests are best served by focusing on those areas. In other words, these organizations need a shared narrative about what is happening in the economy, a shared vision for what it could and should become, and a shared theory of what basic types of interventions will get the economy from here to there. This includes foundational principles, such as that advanced industries are necessary enablers of regional prosperity, and that inclusion—regardless, of race, gender, the neighborhood one lives in, or other characteristics—is essential to being competitive.

A strong orientation capability is needed to accomplish this because no two organizations in a region have access to the same information about the economy. The world is awash in data, but the practice of regional economic development remains rife with blind spots. Community colleges may not know how skill demands in leading companies in key industries are changing, given the emergence of generative artificial intelligence and other shifts. And those companies, which may perceive skills gaps in key middle-wage roles, may not know about the students in those community colleges, what barriers they face, or how to change hiring practices to tap into that talent pool. The orientation capability needs to not only shed light on these blind spots, but also establish shared beliefs among a wide range of organizations with an equally wide range of needs and incentives. It matters little whether a company knows what is going on within a community college if the leaders of that company have not internalized that their competitiveness—and the region’s—depend on investing in those talent pipelines.

Too little is invested in this type of strategic research and communication because it is a public good—it provides significant but diffuse and often invisible value. Often underrecognized are the hours and hours of stakeholder conversations required—on top of deliberate data gathering and analysis—to align the region toward a shared vision, theory, and priorities. Moreover, a strong orientation capability can be worth little if other capabilities remain weak (for example, if the integration capability is not building teams to solve problems elevated by the orientation capability). As the following examples show, philanthropy can effectively address this resource gap, and in doing so, ensure that the often-overlooked wisdom and reach of community-based organizations are incorporated.

Despite a foothold in legacy industries such as oil and aviation maintenance, Tulsa, Okla.’s economy has stagnated in recent decades, ranking among the bottom of comparatively sized regions on economic growth and prosperity from 2011 to 2021 in Brookings’ Metro Monitor. The George Kaiser Family Foundation (GKFF), a $5 billion philanthropy affiliated with the Tulsa Community Foundation, recognized that the region’s economic underperformance was contributing to challenges in some of the foundation’s areas of focus, such as early childhood education. Recognizing that “to provide long-term opportunities for Tulsa’s families, we need to invest in our local economy and prepare Tulsa for the jobs of the future,” in the words of GKFF Executive Director Ken Levit, the foundation created a quasi-independent subsidiary, Tulsa Innovation Labs (TIL), that could advance the region’s position in the innovation economy.

An early step was using its capital to commission an analysis to assess Tulsa’s assets and competitive advantages. The analysis identified Tulsa’s specific “tech niche” in virtual health, energy, cybersecurity, and advanced air mobility (AAM). That evidence base, in turn, helped TIL orient regional leaders who were considering a range of potential federal investment opportunities. They aligned around AAM as a core focus and foundation of the region’s BBBRC and Tech Hubs applications for federal funding, which yielded $38 million and $51 million awards, respectively.

Illinois has a wealth of business and civic institutions, research universities, and economic development organizations, as well as a diversified economy with multiple legacy industries and emerging economic strengths. For those reasons, when new federal funding opportunities emerged, the response across the state was fragmented, as different groups saw opportunities to advance initiatives in their domains. One early EDA call for proposals garnered at least 20 discrete applications from the Prairie State. Amid this frenzy of activity, one philanthropic leader raised a critical question: “How do we, as a local philanthropy, sit alongside all this federal money and help our partners bring as much of it as possible to our region?”

State, industry, research, civic, and philanthropic leaders quickly recognized that they needed to create a forum and process for leaders who had been developing proposal concepts in silos to come together to identify and prioritize investment-ready opportunities, linking key stakeholders in support of them.

Philanthropy provided critical rapid and flexible capital to Innovate Illinois, which leveraged the capacity and infrastructure of existing entities—including P33, a tech-focused economic development and talent organization, and the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign—and could act as a neutral convener to bring together experts across domains to rigorously assess and strengthen the most promising applications. As part of this effort, Innovate Illinois stakeholders surfaced four priority pillars based on the state and its universities’ research and development assets: Beyond Silicon (quantum), Beyond Carbon (clean energy and water), Beyond Biology (synthetic biology and precision fermentation), and Beyond Boundaries (inclusive workforce). The result: a $51 million Tech Hubs award supporting precision fermentation and biomanufacturing, a $500 million state investment in quantum computing to accompany a second Tech Hubs designation, and a National Science Foundation (NSF) Regional Innovation Engines award of up to $160 million over 10 years to advance clean water technologies, among other public recognitions and investments.

Activate key business leaders

Almost no inclusive growth intervention can be effective or achieve the necessary scale without the active engagement of business leaders from relevant industries. One reason is that, as described previously, information from these businesses is essential. A region that relies on publicly available labor market information will never be able to build workforce pipelines that reliably connect disadvantaged students to the good jobs of the future. Likewise, a region that doesn’t have firsthand information about the innovation needs of leading companies in key industries will never be able to reliably steer underrepresented entrepreneurs toward wealth-generating business opportunities.

It is essential that a critical mass of businesses in strategically relevant parts of the economy is convened. This gives nonprofit and public sector partners an opportunity to learn what an industry needs without each having to reach out to businesses individually, which is inefficient for everyone involved. More importantly, it allows business leaders to collectively define what matters to their competitiveness, decide what they are willing to work on together, and hold their peers accountable for contributing to those efforts (in a way that nonprofit organizations cannot if reliant on business funding).

Successful activation of the private sector requires giving businesses a forum to arrive at their own conclusions about shared problems and hypotheses about how to solve them. But what this should ultimately yield is a genuine desire among businesses to partner with external entities to test those hypotheses, figure out what works, and scale those solutions—with private sector funding. Moving from shared problems to collective action, however, often presents classic collective action challenges: It requires individual firms (sometimes competing ones) to incur real costs (contributing time, money, and/or information) to produce potential, not guaranteed, shared benefits. Some firms may naturally decide that it is in their interest to invest, but this can be catalyzed and accelerated by philanthropy providing the risk capital to incentivize business participation and demonstrate the value proposition of self-interested private investment. Funders can also support nonprofits to participate in these iterative problem-solving exercises with businesses.

In New Orleans, as leaders considered what it would take to rebound from the COVID-19 pandemic’s significant impact on the labor market and key industries, it became clear that immediate challenges were compounding long-term ones related to the region’s stagnating and unequal growth. This, in turn, led to shared recognition of a critical shortcoming of the region’s workforce development efforts: that workforce development, educational institutions, and industry leadership largely operated in silos without alignment. As described in a Good Jobs Challenge proposal led by the city of New Orleans Office of Workforce Development, workforce development efforts in the region “have been ad hoc and too often focused on a particular employer or cluster of employers, occupation, or training provider.” While the proposal was ultimately unsuccessful, its development heightened a shared understanding that industry was insufficiently engaged in workforce development efforts.

Seeking to capture the momentum created by organizing that proposal, the Greater New Orleans Foundation (GNOF) used its relationships and influence as well as operating support—in partnership with the Office of Workforce Development—to convene partners around a new sector partnership approach that put employers in the driver’s seat. With the city’s support, GNOF and its partners are utilizing uniquely flexible ARPA funds to de-risk collaboration among employers in the same industry, using public funds to essentially seed a demonstration of how, by working together, they can improve talent development outcomes for each. In doing so, these partners are making the case for ongoing employer investment in talent initiatives as a “must do” for their businesses rather than a “nice to do” for the community. The region now has sector partnerships with robust private sector leadership emerging in construction and green infrastructure, health care, transportation and logistics, and advanced manufacturing.

The Rose Rock Bridge initiative in Tulsa provides another example of philanthropy mobilizing private sector actors toward shared economic and equity goals. Spearheaded by TIL, with capital support from GKFF, the $50 million “venture studio,” dubbed Rose Rock Bridge, has activated significant corporate investment. It serves as a hub for inclusive entrepreneurship and innovation by recruiting promising energy startups from across the country and connecting them with the region’s Fortune 500 energy companies.

Philanthropic leadership significantly lowered barriers to private sector engagement. GKFF’s upfront investment in its staffing and operations reduced risk and made participation easier for the energy companies. In doing so, the Rose Rock Bridge initiative has not only accelerated innovation in the region but also offered clear “on-ramps” for private sector co-investment and ownership. To date, the initiative has succeeded in raising $36 million from energy companies (including $4 million in dedicated funding for overhead and governance), helped launch five new companies, and continues to scale both in the energy sector as well as other industries.

Although Rose Rock Bridge was established prior to Tulsa securing its federal investments, TIL now seeks to adapt this successful model of catalyzing private sector engagement to the region’s BBBRC- and Tech Hubs-funded advanced aerial mobility cluster. This progression demonstrates how early philanthropic investment can be leveraged to align industry around emerging federal priorities.

Integrate teams

The capabilities described thus far get a region to the point that a team of organizations representing all the necessary positions are assembled on the field, knowing how to win the game they intend to play and subscribing to a general style of play. But much remains to be done at that point; winning a competition for a share of a desirable industry requires the same discipline and difficult choices as winning a game in any sport. A region needs an entity to act as a coach: stipulating a game plan for a specific opponent (identifying the best approach to solve a complex problem, drawing on evidence from research and efforts in other regions); deciding which players should start the game (objectively assessing organizational capabilities relative to the approach identified); deciding which player should play which position (assigning implementers to complementary roles with minimal overlap but strong connectivity); and making adjustments throughout the season (bringing in new organizations or investments in existing organizations).

This is a rare capability. There are few regions with an entity that can go beyond inviting a cross-sector group of organizations to generally work together in a specific part of the economy (analogous to organizing a pickup game) and instead assemble, guide, and resource a highly effective team to execute in a disciplined way. To varying degrees, federal funding equipped a lead organization in a region to play this role; in some cases, such as the BBBRC, the lead organization was bestowed little control over how funding flowed, while in others, such as the Regional Innovation Engines program, the lead entity was granted more authority to change the components of the project or the recipients of funding. In the case of workforce intermediaries funded via the CHIPS and Science Act, there is wide latitude to use awarded funding—$65 million in the case of Syracuse—to make whatever investments are required to build systems capable of meeting the needs of semiconductor fabs.

Integrating effective teams is an essential capability, but not likely to endure without additional federal funding unless philanthropy steps in. Our analysis shows that local organizations were willing to grant an entity this coach-like authority when the payoff was access to catalytic funding. If it is no longer perceived that the entity (and the advisory body that informs it) has meaningful influence over funding flows, it will lose the ability to orchestrate disciplined execution—the consequence being an ecosystem that generates scattered pilot projects in the face of economic challenges that demand enduring platforms for solving complex problems at scale.

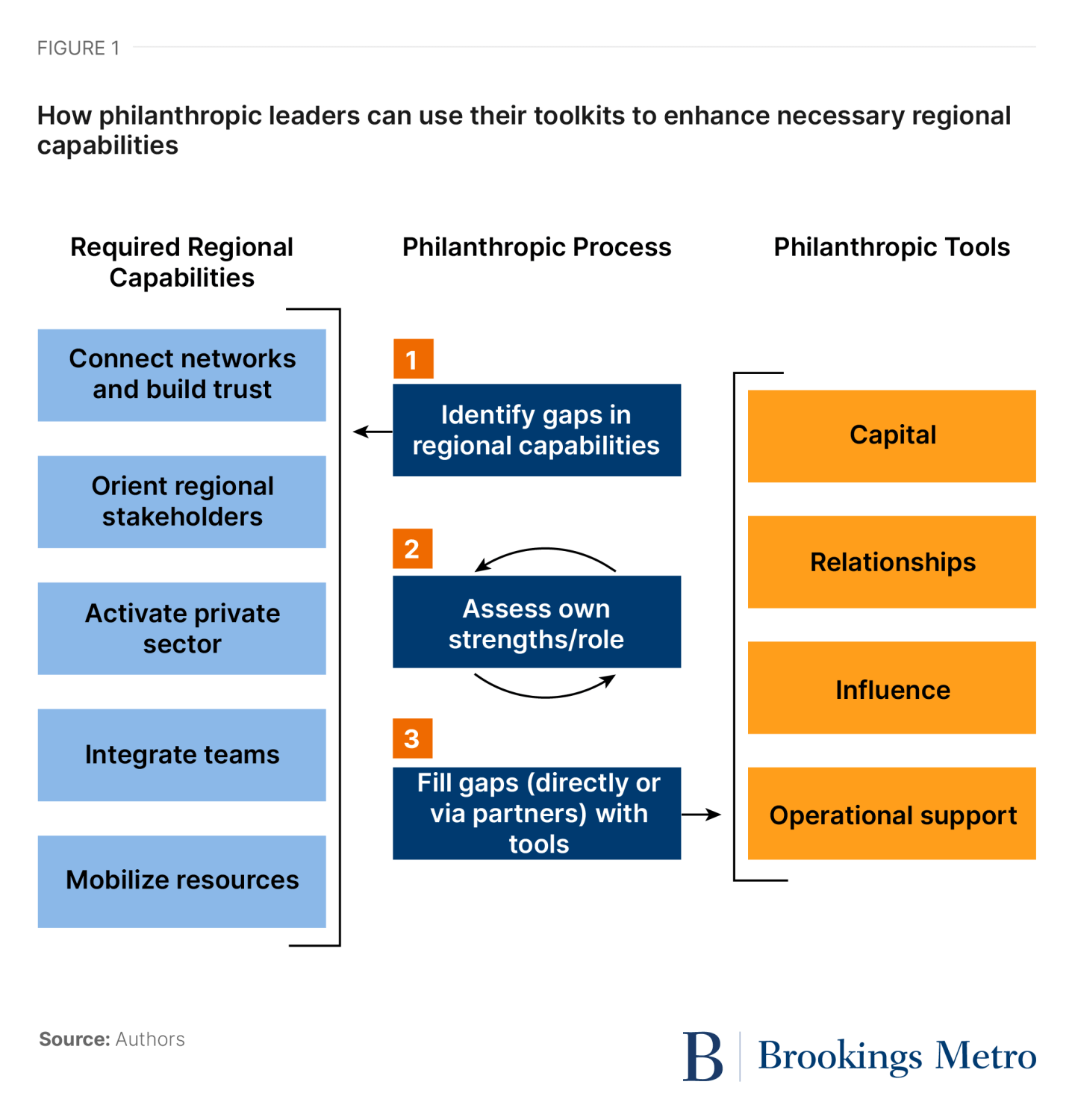

In Fresno, CVCF played a pivotal role in integrating multi-organizational teams to design and deliver investments in inclusive, climate-resilient agricultural innovation. As lead intermediary for the $65.1 million BBBRC award, CVCF coordinated the Fresno-Merced Future of Food (F3) Coalition, thoughtfully aligning partners around a shared strategy. While the majority of grant funding went directly to implementation leads, CVCF allocated $2 million of the award specifically for “partner integration,” which funded governance, facilitation, community engagement, and shared evaluation across three interconnected domains to reduce duplication and ensure cross-sector coordination (see Figure 2).

A key part of the integration function in Fresno was assigning leadership roles based on an objective assessment of each organization’s strengths and capacities, using operational support and informed by existing relationships. As CVCF President and CEO Ashley Swearengin explained, “We pay attention to where people are walking, and then we pour the concrete to the sidewalk. For example, if there’s a lot of natural leadership being exhibited by this particular community college in one area, we asked: ‘Would you be the lead on this?’”

This approach resulted in a two-pronged implementation approach: CVCF worked with larger institutions—such as University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources, University of California Merced, and Merced College—as fiscal sponsors for key initiatives, giving each a clear leadership role and sense of ownership in the broader strategy. CVCF also supported these and other large partners in strengthening their fiscal functions, including developing regranting mechanisms and the coordination capacity needed for collaboration at scale. At the same time, CVCF worked directly with smaller, community-based organizations serving farmworkers and marginalized groups to ensure they had a voice in shaping the strategy and received necessary support—often delivered through subgrants administered by the larger institutions.

In Syracuse, the partnership between CenterState CEO and the Central New York Community Foundation (CNYCF) has been central to organizing and aligning a complex, multi-sector response to Micron’s $100 billion semiconductor investment, backed by $6.1 billion in federal subsidies and $5.5 billion in state tax incentives. While CenterState CEO has served as the region’s strategic lead—securing major projects, shaping policy such as the $500 million Community Investment Fund, and designing scalable workforce models—CNYCF will play a critical role in integrating teams of small, community-based implementation partners to deliver programs at the scale and speed this project requires. CNYCF is able to play this role because it is close to these small, under-resourced organizations, allowing it to assess which are well connected to (and trusted by) specific priority populations and which have the requisite capacity to play certain roles. CNYCF then has the ability to direct resources to the right places to strengthen these organizations’ capacity or address weaknesses.

CNYCF’s role extends beyond deploying capital for program delivery—it is actively mobilizing its operational support to build the organizational infrastructure that small nonprofits need to deliver on Micron’s inclusive growth commitments. Many frontline organizations lack the administrative capacity to manage federal funds, so CNYCF and another local philanthropic partner, the Gifford Foundation, are working to formalize and scale a “Nonprofit University” to help them clarify roles, form effective partnerships, and build foundational systems. CNYCF also seeks to invest in shared services models to fill capacity gaps in HR, finance, and grant compliance. This will allow smaller groups to play critical, focused roles—such as recruitment or coaching—within larger workforce development efforts, making it possible for high-impact organizations to contribute even without managing complex federal grants themselves.

Mobilize resources

Federal funding for place-based industrial strategy projects was, even in the best cases, only a down payment on regions’ economic ambitions. The largest competitive grant projects, for example, delivered something on the order of $10 million per year, typically spread across five projects, each of which might involve several implementing partners. This is a fraction of what is required to stimulate innovation and growth in a prioritized sector—not to mention what is required to ensure that growth is inclusive. Every region will need to mobilize significant additional funding from state governments, philanthropies, and businesses to allow these efforts to maintain momentum in the near term as well as on an ongoing basis over time.

This requires more than storytelling and fundraising. A regional organization or group of organizations needs to first be able to measure the performance of the regional economy and the components of the strategy. This can create urgency for the work overall and confidence that the strategy is working and merits further investment or is at least targeted at problems worthy of investment. Second, to effectively deploy resources in service of the strategy, it needs to be able to accurately assess the performance of the “ecosystem” of organizations involved or potentially involved in implementing projects. It needs to help manage performance by deploying the right kinds of capital with the right guidelines to the right organizations at the right time. This requires an informed point of view about what is happening in the economy, so that the organizations battling the strongest headwinds are not determined to be underperforming (and vice versa). It also requires knowledge of best practices and their true costs; funders are often surprised at the cost per trainee for some of the most highly regarded workforce development programs in the country.

Lastly, this capability needs to be able to blend funding with finance. The creation of “green banks” to accelerate the development and deployment of clean technologies is a good example. The New York Green Bank was capitalized with $1 billion in public funding, primarily from utility ratepayer surcharges, between 2013 and 2017. It has since committed over $2 billion, which has stimulated $8 billion of investment overall through credit enhancement, lending programs, and attraction of private capital. Career impact bonds, such as “pay it forward” or other talent finance models, can have a similar impact in the workforce development context. And housing is a proven area for deploying hybrid public-private funding and finance at scale. For example, the GroundBreak Coalition in Minneapolis-Saint Paul intends to mobilize $5 billion, largely for homeownership and affordable housing, from a $1 billion philanthropic investment by creating new financial products.

These kinds of resource mobilization efforts are essential for regional success, given the investment required to change the trajectory of a local economy and the reality that the federal government is unlikely to offer significant funding for these initiatives.

In Syracuse, CNYCF is helping to anchor long-term inclusive growth by partnering with other philanthropies, civic intermediaries, and partners to raise $150 million in philanthropic contributions to complement public funding for the region’s $500 million Community Investment Fund, examined in detail in the case study. Through tools such as its CNY Vitals dashboard, shared services offerings, and nonprofit training programs, CNYCF is embedding impact tracking and organizational development into the region’s growth strategy. In this case, the foundation is deploying capital along with operational support to promote long-term sustainability. In addition, CenterState CEO and CNYCF are exploring the creation of a housing fund that would similarly leverage private sector capital—providing manufacturers and other regional firms, not just financial institutions, a way to invest efficiently and effectively in local affordable housing. An affordable cost of living is critical for attracting and retaining workers and keeping the region competitive with a good quality of life for the long term.

In Fresno, CVCF is blending public and private capital to sustain the region’s ag-tech transformation and providing operational support for a shared measurement and evaluation system that positions the region for future investment. In addition to leading the region’s successful $65 million BBBRC award, CVCF secured $47 million in state funding for the F3 initiative, including F3 Innovate (formerly iCREATE), a hub for innovation in areas including artificial intelligence for agribusiness, food-energy-water systems, and technology solutions for small famers—continuing to position the initiative for industry investment.

Conclusion

Over the past few years, significant federal investment—and the intense national competitions that allocated much of it—gave many regions an enviable opportunity to catalyze transformation. But what once may have felt like the beginning of a new era of regional investment now risks adding these initiatives to the list of promising and impactful but ultimately incremental and short-lived initiatives that are familiar to regional economic and workforce development, civic and community, and business and industry leaders. To avoid that fate, regions and their leading philanthropies must now confront a dual challenge. First, they must determine how to sustain the progress on programs supported by recent federal funding and keep them relevant to long-term economic growth and inclusion. Second, they must decide how they will respond to new economic and social threats affecting their vulnerable populations and critical industries.

We believe that the approach outlined in this report and the accompanying case studies are an answer for both, offering regions a framework to position themselves to seize and sustain opportunities and weather shocks. The regional capabilities illustrated here—connect, orient, activate, integrate, and mobilize—can be deployed as part of the response to a particular opportunity or challenge, but cannot be built overnight. They are not designed to lock specific organizations or individuals into permanent roles, but instead cultivate a shared capacity for strategic action that is rigorous and strategic, but also iterative and nimble. This flexibility is especially critical now, as regional leaders face unpredictable market fluctuations, growing social polarization, and shifts and uncertainties in federal policy and staffing that complicate their ability to access federal resources, make timely strategic decisions, and continue deploying resources for critical programs and initiatives.

Philanthropy has a vital role. In many of the regions profiled here, philanthropic institutions were essential partners in the early stages—deploying flexible capital, supporting coalition-building, and ensuring inclusion stayed at the center of strategy design and execution. They deployed a range of tools, often in combination, to play those roles; for example, by leveraging existing networks of relationships across Fresno, plus a fresh federal funding opportunity, to mobilize a diverse coalition in service of an inclusive, ag-tech cluster-building strategy.

These efforts are providing determined state and local governments and leaders of companies large and small with opportunities that would have been very difficult and slow to build otherwise. These include capital funds to dramatically expand housing supply and help ensure the affordable cost of living workers need for the long haul (and what companies need to attract and retain workers), high-performing workforce sector strategies and other good-jobs strategies, and stronger and more diverse-owned pools of suppliers to locally capture demand and wealth.

In this evolving federal moment, funders should not lose sight of the often-overlooked capabilities that are difficult to capture in a grant report, and risk being neglected as leadership and staffing inevitably change. To that end, as some of philanthropy’s most respected and experienced observers have long argued in other contexts, it’s crucial that funders think about impact as demanding more than their checkbooks, let alone giving that confines itself to the downstream symptoms of an economy that is not yet working for everyone. The remarkable cases we have analyzed show why funders should not simply recognize the stakes of economic change and assess the impact of their grantmaking bet by bet, but also their position in the broader ecosystem—where their resources, relationships, credibility, expertise, and operational capacity can be leveraged to build and sustain the regional capabilities that will enable long-term economic transformation. Strengthening these regional capabilities in the short and medium term will enable regional coalitions to be ready to seize future state and federal funding opportunities as well as evolving market needs and opportunities.

The challenge now is not just to scale what worked, but to double-down on what mattered, particularly these critical—yet often invisible—regional capabilities for sustaining inclusive growth. Regions that make that leap will be better prepared not only to protect the gains of the past few years, but to lead through what comes next.

Case study series

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

Support from the San Diego Foundation (SDF) made this project possible, and we are particularly appreciative of Mark Stuart for his ongoing support and guidance. In addition, we are grateful to regional leaders who helped inspire, shape, and sharpen this report and case study series, including those at CenterState CEO, Central New York Community Foundation, Central Valley Community Foundation, F3 Innovate, George Kaiser Family Foundation, Greater New Orleans Foundation, Greater New Orleans, Inc., Innovate Illinois, P33, Pritzker Traubert Foundation, and Tulsa Innovation Labs. We thank Alan Berube, Laurel Blatchford, Xavier de Souza Briggs, and Robert Puentes for feedback on earlier drafts. Thank you as well to Francie Genz, whose rigorous work on the “five capabilities” helped shape this effort. All remaining errors and omissions are the sole responsibility of the authors.

-

Footnotes

- As Brookings has documented, “advanced industries” provide a substantial wage premium, holding educational attainment constant. However, their importance extends beyond direct employment impacts. These industries can grow faster than a regional economy’s population, creating tight labor markets and higher wages in all occupations. And in doing so, they allow the growth of occupations that are more widely understood to be relevant to economic inclusion (e.g., health care and construction).

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).