It is an odd time to be a Muslim in America, in part because it depends on which America you happen to live in. Here, too, there are two Americas.

On the one hand, this is a sort of golden age for American Muslims and their place in public life. Sometimes it seems like Muslims are everywhere, even though they’re not. They star in their own television shows; they headline the White House correspondents’ dinner ; they win Academy Awards; they become Snapchat sensations. Some of it is more subtle but striking nonetheless: If you live in a semi-hip urban setting, it’s not unusual to see a headscarf-wearing woman in an ad flanked by a rainbow coalition of other diverse Americans.

This can make it easy to forget the other reality that exists alongside the liberal pop-culture embrace of Muslims. The increase in anti-Muslim bigotry and other forms of discrimination against Muslims is well documented. But even if you don’t experience it or see it, you know Islamophobia exists, because it is there on social media. It is also in our president’s rhetoric. It is inescapable.

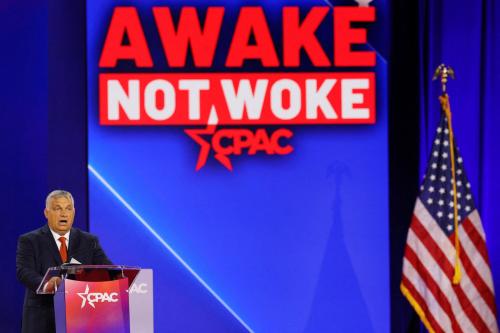

According to polling by University of Maryland professor Shibley Telhami, favorable views of Islam actually increased during the 2016 presidential campaign, but this increase came entirely from Democrats and independents. Among Republicans, favorable attitudes toward Muslims, as people, and Islam, as a religion, remained worryingly low (at around 40 percent and 25 percent, respectively). This is the America that the lawyer and writer Asma T. Uddin is most concerned with in her book “When Islam Is Not a Religion.” The title comes from the growing movement to paint Islam as a political ideology rather than a religion. If Islam is not a religion, Uddin writes, then it cannot claim the protections that U.S. law grants to religious expression. This, in effect, is how many Christian conservatives reconcile the seemingly contradictory positions of advocating for religious freedom for themselves but not for Muslims. In the process, the free exercise of religion, protected and guaranteed by the First Amendment, becomes yet another victim of partisan polarization.

That such an argument about Islam would come from Christian conservatives is somewhat ironic. After all, the notion that religion should remain private and personal is precisely the argument that secular liberals employ against Christians when it comes to issues like abortion and baking cakes for same-sex weddings. Conservatives bristle, rightly, at the idea that their faith commitments should not influence their politics. Why, then, would they insist that American Muslims become the very thing — in effect good, docile secularists — that they refuse to be?

Uddin is at her best and most passionate when discussing how this strain of anti-Muslim sentiment has affected her as an observant Muslim who shares some of the concerns of Christian conservatives regarding secular intolerance of sincerely held religious conviction. She was part of the legal team representing Hobby Lobby, the arts-and-crafts company that refused to provide certain contraceptives to employees as mandated by the Affordable Care Act. She worries that Muslims have become too closely tied to the Democratic Party, noting for example that “the Right’s tribal opposition to the political Left multiplies the Right’s hostility toward Muslim religious rights.”

Throughout the book, Uddin reserves most of her criticism for Republicans and conservatives, since they are the ones imperiling, indirectly or directly, the safety and security of Muslims through the rhetorical delegitimization of Islam, along with practical measures like opposition to mosque construction in local communities. But she also points to the occasionally awkward embrace between Muslims and the left and wonders whether that awkwardness might one day reveal deeper tensions. Many Muslims (including myself) are relieved that at least one of the two major parties is taking it upon itself to defend Muslims during a period of uncertainty. But there is, at the same time, an undercurrent of growing discomfort among avowedly conservative Muslims. Will Muslims who openly criticize the left’s stances on gender, abortion and gay rights still have a place in the Democratic Party?

As a conservative Muslim friend once told me: “I can sense the disdain from the Democratic Party towards my faith, even as they don a cape against Islamophobia. The underlying view Democrats have [about] anyone seriously religious is that they’re, at best, silly and gullible, and at worst, dangerous.” Uddin cites the infamous example of Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) telling appeals court nominee Amy Coney Barrett, a practicing Catholic, that “the dogma lives loudly within you.” It is difficult to imagine Feinstein saying this to a Muslim judicial nominee, but it is an affront to American traditions of religious liberty all the same and one that could be easily turned against conservative Muslims in due time.

What seems to be a book about the place of Muslims (and the anti-Muslim sentiment they are subjected to) in the Trump era is actually something different: It builds into a stirring defense of religious freedom, which, try as we might, is inseparable from human freedom. As Uddin writes: “It’s not our beliefs that religious liberty protects — it protects us, the humans who hold those beliefs. Put another way, religious liberty protects believers, not beliefs.”

It shouldn’t matter, then, whether someone is religious or not, since most Americans believe in something strongly enough for them to hope that the government will not interfere in those beliefs. These beliefs, and those who believe them, seem to be in growing conflict with each other. Americans no longer share the same starting premises, if they ever did, on what it means to live well. We’re perhaps more aware of it today because our fellow citizens — angry, impatient and increasingly educated — are more willing to express their “uncivil” opinions and have access to social media platforms where they can do precisely that. Uddin’s careful, fair and often quite powerful account offers up religion not as a source of our divides but as a window into how we might better manage them. Like all debates around autonomy and choice, the debate over religious freedom — and the place of Muslims in American public life — is one that speaks to a fundamental question, perhaps the fundamental question of the Trump era: how to live together with deep difference, not in spite of it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

For religious American Muslims, hostility from the right and disdain from the left

August 5, 2019