The year 2015 marked a historic milestone in the struggle for LGBTQ+ rights: the Supreme Court’s recognition of marriage equality. The court’s ruling both reflected and promoted an incredible sea change in American life. In the two decades prior to the decision, public opinion on LGBTQ+ rights improved more rapidly than any other attitude in the history of American opinion polling.

Growing up amid these changes, today’s LGBTQ+ youth are the beneficiaries of tremendous social progress. The markers of this progress are easy to find. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth are coming out earlier than ever before. Whereas older generations report not coming out until their mid-20s, those born in the 1990s report coming out while still in high school. Not only are today’s LGBTQ+ youth coming out at younger ages, they’re also coming out in greater numbers. Driven largely by a rapid increase in bisexuality among younger cohorts of women, the number of young people identifying as LGBTQ+ continues to rise.

The increasing visibility of LGBTQ+ youth is actively reshaping America’s schools. Beginning in 2015, the Department of Education’s School Survey on Crime and Safety began asking principals whether their school had a recognized club to “promote acceptance of sexual orientation and gender identity (e.g., Gay-Straight Alliance).” In 2015, 12% of middle school principals and 50% of high school principals reported having such clubs. By 2017, principals reported gay-straight alliances in 23% of middle schools and 59% of high schools, including 76% of suburban high schools, 72% of urban high schools and 39% of rural high schools. In 23 states, these school-level clubs are supported by state-level policies explicitly prohibiting bullying on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

In so many ways, it would seem that there’s never been a better time to grow up LGBTQ+ in America. And yet, in the same year that the Supreme Court ruled in Obergefell, America also reached another milestone in its recognition of LGBTQ+ populations. Although less momentous, it too was the result of generations of research and advocacy. For the first time ever, the CDC included a question about sexual identity in its national Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS). This survey provided the first population-based, nationally representative portrait of sexual minority high school students since the Add Health study two decades prior. The results were sobering. Among students who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or “not sure” (LGBQ), about 40% reported being bullied, 39% reported having “seriously considered” suicide, and a full 56% reported clinically significant signs of depression. Although some of the CDC’s estimates were later shown to be inflated by “mischievous responders,” these bullying and mental health disparities remained remarkably stable across analyses.

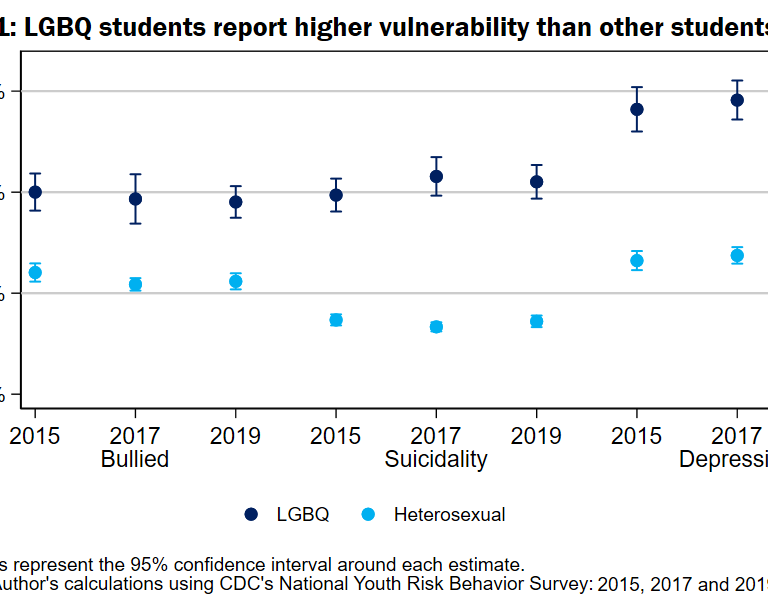

Since 2015, the story told by America’s LGBQ high school students has not improved. (Because these data do not assess gender identity or sexual identities beyond L/G/B/Q, I refer here only to LGBQ students). In Figure 1, I present estimates from the 2015, 2017, and 2019 National YRBS. For LGBQ respondents, the results show no change in bullying, no change in suicidal ideation, and a slight upward trend in depression. On every measure, LGBQ students report substantially worse outcomes than their straight peers: LGBQ students are about 70% more likely to report bullying, twice as likely to report suicidal ideation, and three times more likely to report depression. Population-representative data on transgender students are more limited. However, the data that are available provide a picture of an especially vulnerable population, reporting outcomes similar to or worse than those reported by LGBQ students. Early indications suggest that the experiences of LGBTQ+ teens only worsened during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Compared to social and legal contexts faced by generations before them, things have surely gotten better for today’s LGBTQ+ youth. But the realities reported in the YRBS provide a painful perspective on how far America still needs to go to achieve equality for its LGBTQ+ populations. That perspective is all the more urgent in the current moment.

Following the recent period of historic progress, a far-reaching and well-orchestrated backlash against LGBTQ+ rights is now in full swing. After seeing just a handful of anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in state legislatures in 2018 and 2019, the past three years have witnessed a record-breaking number of anti-LGBTQ+ measures proposed and passed across the country. In just the first three months of 2022, lawmakers proposed 238 bills restricting the rights of LGBTQ+ Americans. Many of these bills specifically target LGBTQ+ students’ experiences within schools. These legislative initiatives also appear to have emboldened a wave of LGBTQ+ book bans, efforts to dismantle gay-straight alliances, and the forced removal of LGBTQ+-affirming materials from school spaces.

And so, this year’s LGBTQ+ Pride Month comes at a perilous time. A growing body of population-representative data reveals just how far away the promise of equality remains for today’s LGBTQ+ youth. At the same time, rising waves of anti-LGBTQ+ legislation offer a stark reminder that continued progress toward equality is by no means assured. To push back against this tide, there is much that can be done. Citizens can support policies protecting LGBTQ+ students and teachers. School leaders can promote gay-straight alliances, which serve as a critical protective factor at times when LGBTQ+ bullying is on the rise. And individual teachers can continue to make a tremendous difference, since the presence of even one LGBTQ+ affirming teacher in a school is associated with significantly better academic and emotional outcomes for LGBTQ+ youth.

Although Pride Month comes at the end of the school year, this is no time to take a break. When even foundational rights like marriage equality appear newly uncertain, this year’s Pride is a time not only to celebrate, but to organize.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).