Over the past decade, a plethora of programs have been created to prepare students for careers in technical fields. These schemes often allow high school students to earn college credits, develop relationships with possible employers, and/or receive career guidance and mentoring.

But most remain small, typically serving a few dozen students at a time. Even with more expansion—which many experts warn will require additional buy-in from employers—they are unlikely to reach the approximately 5.5 million youth aged 16 to 24 who are neither in school nor employed.

American Job Centers: Good, but with limited reach

The federal government funds employment services and training for people who may lack the skills to find a job on their own. Operating through state partnerships and hundreds of one-stop offices throughout the country, these American Job Centers, as they are currently called, help people seeking jobs, from simply providing information on which companies are hiring in the area, to giving a full-on skills assessment and assignment to a specialized program of study.

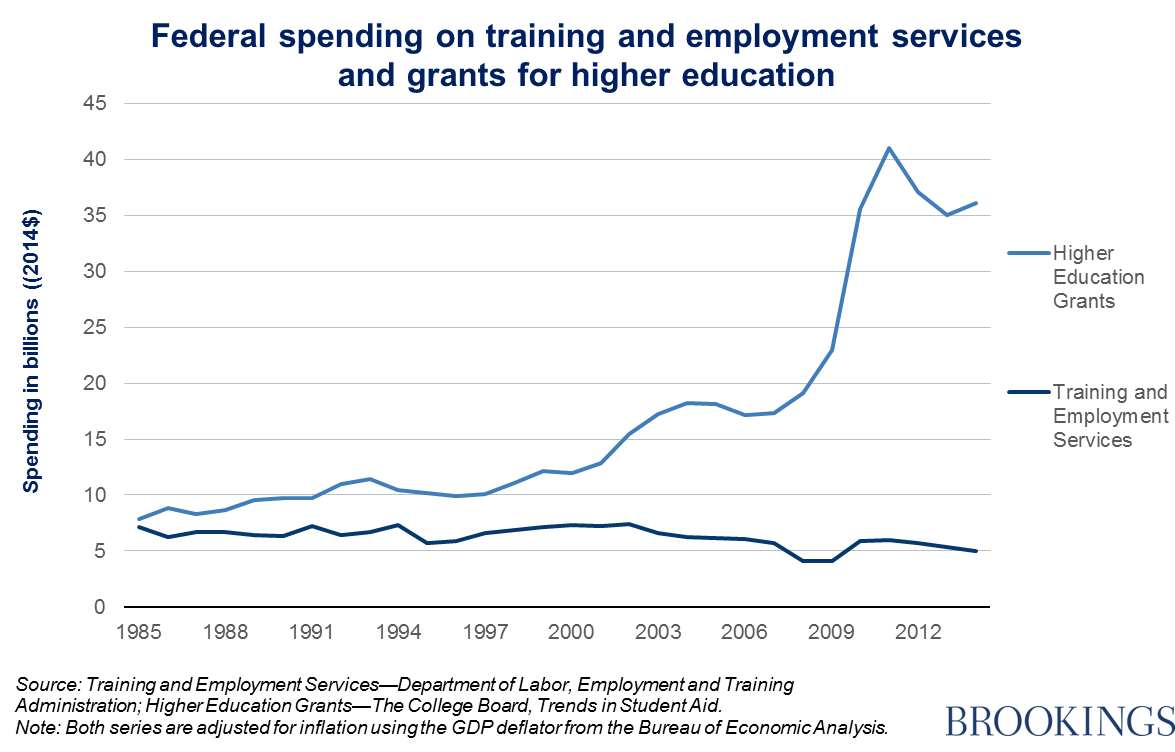

But the more intensive (and more expensive) services can reach very few, especially youth, because of a lack of funding. Federal spending was just $5 billion in 2014, down more than 30 percent from $7.3 billion (adjusted for inflation) in 2000.

To put these numbers in context, the federal government currently spends more than $35 billion annually on direct grants to individuals attending college. The spending gap between workforce training and higher education grants was all but nonexistent in the mid-1980s, but has ballooned since 2000:

Connecting training and employment assistance with financial aid assistance

There is an urgent need to connect up training and employment services with financial aid. A person may receive guidance and a tailored study program from a one-stop center. But they rarely get any direct financial assistance. Perhaps they will be told about federal financial aid. Accessing grant money for higher education means filling out the FAFSA, however, a notoriously complicated government form, and one-stops are seldom able to help.

On the other hand, many of the people filling out the FAFSA—perhaps with the help of volunteer organizations that target traditional students—may get some grant money, but receive little or no advice on the skills they may need to get a job.

Those getting good advice on appropriate learning struggle to get money, while those getting money struggle to know how best to spend it. Waste is the predictable result. Those receiving employment services should get assistance completing the FAFSA. People filling out the FAFSA should receive the labor market information and skills assessments of individuals going through employment services, increasing the chances they’ll choose a course of study that leads to a job, saving them and the government money.

This is, in short, a no-brainer.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Federal education grant money is a terrible thing to waste

September 21, 2015