As inflation surged after the COVID pandemic, there was a rapid and sizable monetary policy tightening in the U.S. and other advanced economies. In the past, these tightening episodes triggered external distress in many emerging markets, as external finance became more expensive, currencies weakened, and capital flows reversed. Think of the debt crisis of 1982, the Mexican crisis of 1994-95, or the Asian financial crisis of 1997-98. Yet in 2021 and 2022, there was little evidence of such stress in major emerging markets. Their increased resilience has been attributed to a combination of factors, including strengthened macroeconomic frameworks, independent and credible central banks, larger foreign exchange reserves, and the adoption of floating exchange rates.1

In this paper, we show that the narrative of improved resilience is well-grounded for large and well-established emerging market economies (such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Mexico, Poland), which we term the “first-tier.” At the same time, however, many emerging markets and developing economies fall outside that group. Some, such as Ghana, Sri Lanka, and Zambia, experienced outright external defaults, while many others are facing external distress—characterized by persistent repayment difficulties and heavy reliance on International Monetary Fund (IMF) lending.

We classify emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) into three groups:

- The first tier comprises members of the G20, OECD, European Union, and the ASEAN-5. These economies are frequently the focus of academic and policy studies, reflecting better data availability and their growing importance in the global economy.

- The second tier consists of economies often considered frontier markets, such as Ecuador, Ghana, and Pakistan. These economies tend to have smaller economic size, lower incomes, and more limited integration with global financial markets compared to the first-tier group.

- The third tier includes low-income countries that either lack meaningful access to international capital markets or are fragile and conflict-affected, such as Ethiopia, Mozambique, and Myanmar.

Diverging indebtedness

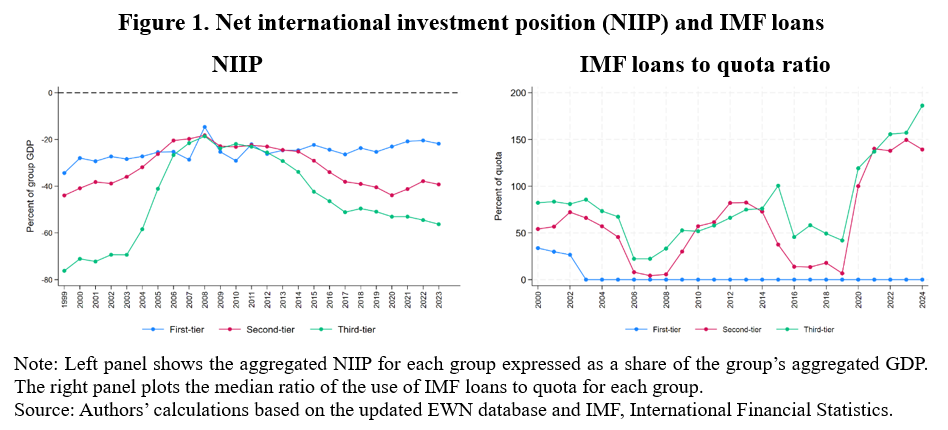

Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), first-tier economies have generally strengthened their external positions and reduced reliance on official lending, but second- and third-tier countries have seen a deterioration in external balances and continue to depend on external assistance when facing shocks (Figure 1). In particular, many second- and third-tier EMDEs have experienced a substantial buildup of external imbalances since the GFC, with a simultaneous rise in external debt and a decline in foreign exchange reserves. This points to greater dependence on foreign capital to finance domestic activity, and a weakening of capacity to absorb external shocks.

These charts show the pattern of net international investment positions of each of our groupings of countries (stable or even improving for first- and second-tier countries after the pandemic) and the sharp increase in IMF lending to second- and third-term groups.

External financial distress remains persistent and concentrated

A range of external financial distress indicators underscores the heightened vulnerabilities of second- and third-tier EMDEs. The external debt-service burden—measured by the ratio of public and publicly guaranteed external debt service to government revenue or to exports—has more than doubled between 2010 and 2023. Many second- and third-tier countries are not fully servicing their external obligations, and hence have accumulated arrears. And these economies persistently depend on IMF lending to address balance-of-payments pressures, stabilize macroeconomic conditions, or avert full-blown crises. While pre-emptive engagement can be appropriate, global shocks such as the GFC and the COVID-19 pandemic pushed many of these economies into distress, prompting a marked increase in IMF support.

Based on these observations, we identify episodes of external financial distress—capturing milder forms of distress beyond full-blown crises—using a comprehensive set of indicators: sovereign defaults, arrears, partial defaults, and reliance on IMF lending. Figure 2 suggests that roughly 40% of second- and third-tier economies remain financially distressed, even if not in outright default, while the share of first-tier economies in distress has declined substantially over time.

What determines the likelihood of financial distress? We find that higher external debt and lower foreign exchange reserves predict the onset of external distress, and also that institutional quality matters: The adverse effect of weak external positions is amplified in countries with weak institutions but diminishes in countries with strong institutions.

In sum: Treating emerging and developing economies as a single group obscures crucial growing differences in external resilience. While several frontier markets have strengthened their policy frameworks and deepened financial integration, many remain externally fragile. Full-blown crises are only part of the story: Many countries hover near distress thresholds, highlighting the need for early warning frameworks that track external balance sheet risk.

Looking ahead: An uneven road

With global risks elevated, financial fragmentation rising, and geopolitical tensions intensifying, many vulnerable EMDEs face a challenging environment. Capital flow reversals or renewed global risk aversion could quickly expose weak external positions. For policymakers in these economies, rebuilding external buffers, improving liability structures, and strengthening institutions will be essential to reduce vulnerability to future shocks. The uneven progress of the past decade suggests that resilience gains cannot be taken for granted—and that many EMDEs remain just one global shock away from renewed and acute external stress.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).