No, President Obama’s upcoming executive order extending LGBT protections to federal contracting and procurement is not illegal, an overreach, or unconstitutional. It is perfectly consistent with federal law, presidential power, and precedents set by prior chief executives—Republicans and Democrats. Opposition to an executive order too often takes the form of charges of abuses of power. So, it’s time for another reality check on executive orders. Here are five important takeaways on the new executive order.

1. It’s not part of unprecedented use of executive orders.

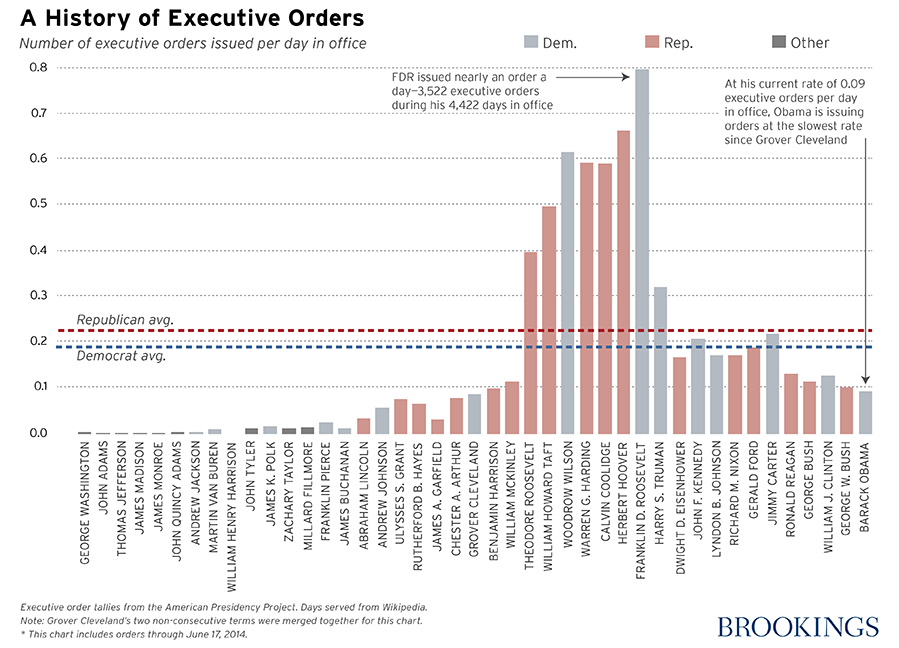

Data show that President Obama has been less aggressive than his predecessors in issuing executive orders. Below is an updated chart of the rate at which presidents issue executive orders, similar to one we posted in January.

It shows that even with the two executive orders issued this week, President Obama is more restrained than prior presidents in using this power. President Obama issues an executive order, on average, about every 11 days. President George W. Bush issued them every 10 days. President Reagan issued about one a week. President Carter issued more than one every five days.

During this year’s State of the Union Address, President Obama committed to using more executive action in his second term. However, since January, he has issued 14 executive orders. That compares to 11 for President Bush, and 18 each for Presidents Clinton and Reagan, during the same period in their sixth years.

That said, the sheer numbers do not reflect the scope or extent of those executive orders. But claims that President Obama is issuing more than his predecessors is just flat wrong—and continues to be a talking point completely at odds with real data.

2.The LGBT contractor protection order is not illegal.

Presidents have authority to set policies that govern federal contracting and procurement. Why? Because Congress authorized the executive to do so. The authority comes from the Federal Property and Administrative Services Act of 1949 (FPASA). This law provides presidents substantial authority to manage federal procurement through executive action. Presidents of both parties, since the passage of the law 65 years ago, have relied on it. In a very basic way, it recognizes that procurement is a fundamental aspect of modern government, and as chief administrator, the president must have authority to ensure that the system runs properly.

Is FPASA a blank check for presidents? No. Federal courts have been clear that presidents cannot use authority under FPASA to produce procurement policies that are inconsistent with other federal laws. However, in AFL-CIO v. Kahn (1979), the DC Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that through FPASA, the President had “particularly direct and broad-ranging authority over those larger administrative and management issues that involve the Government as a whole.” (See CRS Report “Presidential Authority to Impose Requirements on Federal Contractors”.)

Congress gave the president this power; in its 65 years of use, Congress has opted not to take that power back; and federal courts have clarified that the legislative intent of FPASA was to offer presidents substantial discretion in the procurement arena, even in areas of non-discrimination policy.

A final note on this point: federal contracting must comport with the US Constitution. If a court were to reject the statutory basis for the executive order (i.e., for lacking “a close nexus” to “economy and efficiency” under FPASA), the president could invoke a constitutional equal protection claim. How a court would rule in that context is unclear.

3. It is not unique to use executive orders to change contracting rules.

Numerous presidents have used executive orders, invoking the FPASA, to influence the manner in which contracts and procurement systems are run and managed. Some of those changes have been explicit efforts to improve “economy and efficiency” as the letter of the law prescribes. Others have dealt with social and demographic considerations like Indian issues (Reagan’s E.O # 12328); age discrimination (LBJ’s E.O. # 11141); race, color, religion, sex, or national origin (LBJ’s E.O. # 11246); and service-disabled veteran businesses (George W. Bush’s E.O. # 13360). It also conforms with pre-FPASA efforts in this arena such as FDR’s E.O. # 8802, barring racial discrimination among defense contractors. Each has stood the test of time and remains a part of federal contracting rules, not because Congress passed specific legislation but because presidents ordered it.

4. The new executive order doesn’t institute affirmative action.

Previous efforts to deal with social policies through procurement-centered executive orders involved affirmative action issues (see Liberty Mutual v. Friedman [1981]). The executive order will extend LGBT protections to federal procurement; it will not require employers to have quotas for hiring LGBT employees. It will require employers to ban discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation. Employees cannot be fired or refused a job offer simply because they are LGBT. The executive order will extend to the LGBT community the same procurement market protections that are extended to racial, ethnic, and religious minorities; women; and individuals with respect to age.

5. The executive order doesn’t force anyone to do anything.

Federal courts have been clear about participation in federal contracting: it is not a right, it is a choice. The executive order does not require all private employers to comply with sexual orientation-related anti-discrimination policies (as the Employer Non-Discrimination Act [ENDA] would have). It simply asserts that if a private corporation chooses to participate in the federal procurement process, then there are qualifications for that participation. The courts have been clear on this point: the government has the power to set such procedures, qualifications or requirements, and if a private enterprise does not agree with them, they can opt not to compete for a federal contract.

Such requirements may well be controversial, and some have argued that individuals who work for federal contractors do not consider participation in the procurement process to be a choice (though courts have explicitly rejected that argument). However, the case law exists and that standard is not one devised by a president seeking to unilaterally expand his power. Instead, it is one asserted by the judiciary as a legal reality in federal procurement.

Click through to read Congressional Research Service’s “Presidential Authority to Impose Requirements on Federal Contractors,” which provides a comprehensive review of these issues.

Click through to access the text of the FPASA.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Executive Orders & LGBT Protections for Federal Contractors

June 19, 2014