This article originally appeared in Real Clear Markets on May 24, 2017.

One of the great advantages of the United States has, at least historically, been the nation’s sheer scale. With almost four million square miles of territory, there has almost always been somewhere to go to find land, or at least a living.

But the economic geography of the nation has shifted. Productive activity is increasingly concentrated in certain cities and their surroundings. Four in ten Americans are urban dwellers. One result of this shrinkage of economic activity has been to drive up the value of land in the most prosperous places. This is a natural process, of course, for which there is a simple solution: greater population density. Three times as many people live on the island of Manhattan as in Wyoming. You might argue that economic activity should simply be spread around more thinly – say by relocating advertising agencies from Madison Avenue to Mountain View. But this is not how market economies work.

So, people who want greater opportunities can simply move to the prosperous areas. Or at least, that’s the theory. In practice, geographical mobility has been on the decline in recent decades, especially among less-skilled workers.

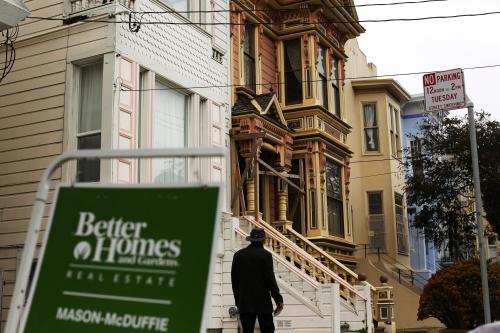

Why? One reason is that housing is too expensive in the most prosperous areas, which means that only those with higher earnings are therefore able to live in them. And why is housing too expensive? Because land use is over-regulated, as Ed Glaeser shows in a recent paper. The rise of “exclusionary zoning,” designed to protect the home values, schools and neighborhoods of the affluent, has badly distorted the American property market.

The rise of “exclusionary zoning,” designed to protect the home values, schools and neighborhoods of the affluent, has badly distorted the American property market.

As the legal scholar Lee Anne Fennell points out, these rules have become “a central organizing feature in American metropolitan life.” Nineteen out of twenty residents of the largest fifty U.S. cities now live in a jurisdiction with some form of zoning. Of course not all zoning is bad. City planners have to balance different needs, and separate certain kinds of land use. We do not generally want power plants mixed in with residential apartments and houses. But zoning becomes exclusionary when it operates simply to separate households based on their economic resources. Exclusionary zoning is bad for the economy: Enrico Moretti and Chang-Tai Hsieh estimate that the U.S. economy would be 10 percent bigger if three cities (San Francisco, San Jose, and New York) had the zoning regulations of the median American city.

But there are social costs too, not least in the perpetuation of inequality across generations. Wealthier Americans are incentivized to protect their neighborhoods as enclaves of affluence, in part to protect the value of their property asset, and in part to control access to other goods, such as high-quality public schools. Homes near good elementary schools are more expensive: about two and half times as much as those near the poorer-performing schools, according to an analysis by Jonathan Rothwell, in large part because of tight restrictions on land use. In Seattle, single-family zoning covers 72 percent of land in the attendance areas of the 13 top-rated public elementary schools.

“The segregation of the rich—which is growing rapidly in U.S. metropolitan areas,” write UCLA economists Michael Lens and Paavo Monkkonen, “results in the hoarding of resources, amenities, and disproportionate political power.”

Those of us with high earnings are able to convert our income into wealth through the housing market, with assistance from the highly regressive mortgage interest deduction. We then become highly defensive—almost paranoid—about the value of our property, and turn to local policies, and especially exclusionary zoning ordinances, to fend off any encroachment by lower-income citizens, and even the slightest risk to the desirability of our neighborhoods.

These exclusionary processes rarely require us to confront public criticism or judgement. They take place quietly and politely in municipal offices, and usually simply require us to defend the status quo. This is not a partisan point: if anything, more liberal cities tend to have the toughest zoning exclusions. But this is not just an individual moral failing: public policy at both local and national tends to exacerbate these trends, as Fennell argues:

“With exclusionary zoning in place, the purchase of a large quantity of housing is effectively bundled with the opportunity to live in a “good” neighborhood and to send one’s children to the best public schools. Thus, many people feel that if they want the good life for themselves and their children, they have to buy an expensive house. Houses in the communities containing the best schools are bid up accordingly. Perversely, federal tax policy makes attainment of these sought-after houses easier for those earning more money; they will be in a higher tax bracket and will enjoy larger mortgage interest and property tax deductions, and therefore lower real costs, than their lower-income competitors.” (One sliver of good news in Trump’s tax plan is the removal of at least state and local property tax deductions).

Exclusionary zoning is a form of “opportunity hoarding” by the upper middle class, a market distortion restricting access to a scarce good (in this case, land), that restricts opportunities (such as good schools) to other children. Those upper middle class voters who oppose more mixed-use housing in their own neighborhoods are what I call “Dream Hoarders,” keeping elements of the American Dream for themselves at the expense of others.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-ed‘Exclusionary zoning’ is opportunity hoarding by upper middle class

May 24, 2017