Executive summary

New York City’s racial equity reports (RERs) are the product of the landmark Local Law 78, which took effect in June 2022. This law mandates an RER on housing and opportunity to go along with certain land use actions, as well as the creation of the Equitable Development Data Explorer (EDDE), which is meant to inform these RERs.

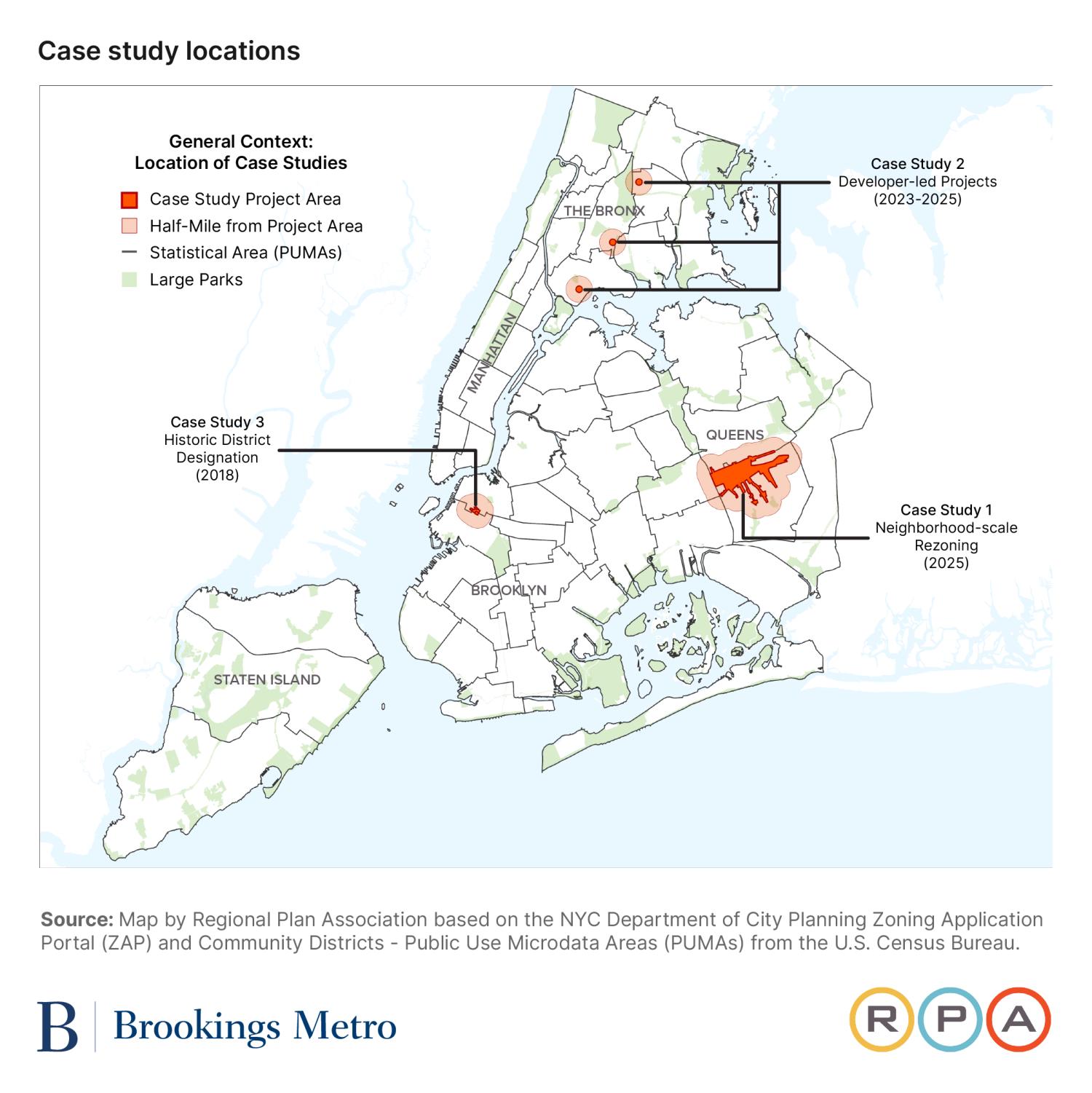

This report seeks to examine the quality and influence of New York’s RERs so far through three contrasting case studies. The first focuses on a large, city-sponsored neighborhood rezoning. The second focuses on a cluster of three smaller, developer-sponsored rezonings. The third focuses on a Historic District designation; while this action would require an RER if done today, this district was designated in 2018, four years before the law took effect. This third case study allows us to examine how race and racial equity discussions were approached before the legislation was enacted and in the context of proposed preservation rather than proposed growth.

Our findings can be read as an early assessment of the law’s implementation and how land use planning and development in New York is responding. The main takeaways are:

- RERs are professionally done, but their quality varies. New York’s RERs have an easy-to-follow template and easy access to the data sources necessary to complete them. This makes threshold requirements easy to meet, which all RERs we examined did. Still, there is some variation in quality between those we examined, with the RER for the large, city-sponsored neighborhood rezoning being of higher quality than the those for smaller, private applications.

- RERs are not often referenced explicitly in media and public testimony. This is despite the fact that the topics they are meant to address—displacement, affordability, and equity—are frequently discussed in both media and public testimony. It should be noted, however, that there is a possibility that the data RERs provided have made their way into these conversations.

- A central contribution of the RER legislation is requiring a formal, substantive statement around the impact of land use actions on racial equity. The inability for initiators of a land use action to elide potentially difficult conversations around race, racialized displacement, and racial equity—even if these conversations remain unreferenced or unresolved—is arguably the most valuable contribution RERs have made so far. Although RERs cannot be conclusively shown to have impacted the ultimate outcome of any of our cases, they have supplied information and perspective about each that would otherwise not have been available.

Finally, the report addresses two broader questions about the overarching purpose and construct of RERs: 1) What are the merits of the current strictly descriptive model as opposed to a more predictive model that would seek to specifically quantify or score a given land use change’s effect on racial equity?; and 2) how do New York’s RERs measure up to Brookings’ proposed rubric for conducting and judging racial equity impact assessment in land use decisionmaking?

While overall, RERs accomplish what they are meant to do, several improvements could be made to the legislation and implementation practices to make them more effective, in particular through greater visibility, enhanced content, and better quality control:

- Visibility: Provide better education on the availability and usage of RERs. It is likely that one of the reasons RERs are not frequently referenced is their relative newness and lack of awareness for not only the public, but even for those parties who often weigh in on land use changes. This might be able to be changed simply through better outreach and dissemination.

- Content: RERs should offer more narrative and meaning, not just supply required data. While RERs and the EDDE provide a substantial amount of data, they could benefit from better contextualizing and expounding on this data in three key ways. First, by integrating various data points in order to enable more comprehensive analysis. Second, by adding more context on the proposal’s likely effects, including a “no action” scenario and the proposal’s quantitative impact on both citywide and neighborhood goals. And third, by incorporating more historical context on race, segregation, and equity in the relevant area.

- Content: Where possible, RERs should also provide better or more granular data. There are also opportunities for RERs to provide more useful or accessible data, such as those focusing on smaller geographies that may be more relevant to a proposed land use action.

- Quality control: Base displacement risk on observed data over time and implement a periodic quality control review of RERs. Much of RERs is informed by a neighborhood “displacement risk” index available in the EDDE. Yet this index is not based on any measurable relationship to observed displacement; this should be rectified. This also demonstrates the need for periodic quality control review of both RERs and the EDDE.

Introduction

New York City’s Local Law 78 stemmed from a larger, nationwide conversation on the intersection of race, equity, and land use, which Brookings and a number of other research, technical support, and advocacy organizations have focused on. This report builds on work conducted by the Brookings Institution’s Center for Community Uplift and the New School’s Institute on Race, Power and Political Economy, especially the January 2025 report “Getting to equitable development,” which discusses the goals and stakes of racial equity impact assessments (REIAs) in land use, the challenges of making them rigorous and useful for decisionmaking, their optimal traits, and the parameters of both New York’s RERs and similar requirements in Washington, D.C., and Montgomery County, Md.

Race has been both an overt and unspoken consideration in land use decisions around the country for decades, if not centuries. And in turn, land use decisions have long shaped patterns of racial segregation and equity. Decisions that have affected access to housing, jobs, and business opportunities—as well as municipal services and urban infrastructure that can contribute greatly toward quality of life—have both been informed by race and affected racial equity. This cycle—one in which land use decisions exacerbate racial inequities and segregation, and patterns of inequality and segregation affect which land use decisions are made—has informed the development of virtually every American city, New York being no exception. Complicating this is the fact that land use decisions designed to reverse this pattern are often viewed instead as leading to gentrification, displacement, or otherwise exacerbating racial inequities in a different but no less impactful manner.

There is nothing inherent or inevitable about land use decisions leading to greater racial inequity and segregation. However, the foundation for changing our current paradigm is to start directly examining a decision’s possible impact on race, segregation, displacement, and access to opportunity. This is what New York’s RER legislation is meant to facilitate.

In evaluating their effectiveness, one might assume New York’s RERs should be measured by their ability to accurately predict the racial impacts of a land use action. However, unlike an environmental impact statement (EIS) or environmental assessment statement (EAS), one or both of which are also required to be submitted along with many land use actions, the intent of RERs is not to predict or attempt to predict the effects of a certain land use action. Instead, they attempt to provide a uniform set of data that can inform the public debate around these land use actions—specifically the debate around race, racial equity, and racialized displacement. The required information falls into five sections:

- Executive summary: A short, plain-language summary of the report.

- Description of project components: Reporting on proposed housing affordability and proposed jobs.

- Community profile summary: Graphs and charts describing neighborhood demographic, socioeconomic, and housing conditions. Includes a displacement risk map. The community profile summary is downloaded from the Equitable Development Data Explorer.

- Narrative statement: A statement describing how the project components and neighborhood characteristics relate to the city’s commitment to affirmatively furthering fair housing and promoting equitable access to opportunity.

- Community profile: A full download of all indicators in the Equitable Development Data Explorer for the local community, the borough, and the city.

In essence, RERs are disclosure documents that provide data and a narrative on a certain geography at a certain point in time, along with better detail on the specifics of a proposed development when it comes to housing and job creation. The arguments over a development’s effect on race, income, equity, displacement, and gentrification—or lack thereof—is not meant to be resolved by these reports. Instead, the RER is meant to simply give this discussion more data points and ensure that all participants are starting with the same set of basic facts. As is made clear by this report’s case studies, all sides of these discussions have the potential to use the RER to illustrate their preferred point of view.

Methodology

Our three cases—a city-sponsored neighborhood rezoning in Queens, a series of developer-sponsored rezonings in the Bronx, and a Historic District designation in Brooklyn—vary in terms of borough, development size, racial composition of the neighborhood, type of land use action, displacement risk, and type of sponsor (public or private). The cases also differ on the quality of the RER and, in one case, if an RER was conducted at all. In evaluating the effectiveness of these RERs, we are looking at three questions:

- Is the legislation followed, both in letter and in spirit?

- Do RERs affect the decisionmaking process when it comes to land use actions?

- Most importantly, do RERs accomplish their purpose of informing the public debate around land use actions?

Proposed land use actions in New York range from noncontroversial to extremely contentious, with concerns around architectural character, infrastructure improvements, scale of development, use of land, and ownership structure, with specifics on cost and type of housing often hotly debated. These debates are generally in the service of two larger questions: 1) How will this development impact the lives of the people currently living in the neighborhood?; and 2) how will this development affect who will live in, work in, and visit the neighborhood? It is the discussion around this second question that RERs are most meant to inform.

To help accomplish this, alongside the mandate to produce RERs for certain land use actions, Local Law 78 also mandated the creation of the Equitable Development Data Explorer (EDDE) which is meant to quantify “displacement risk.” Again, this is not meant to be predictive of whether a given land use action (or non-action) will or will not lead to displacement.1 Instead, it is meant to illustrate the current displacement risk that a neighborhood is experiencing. It is left to the reader to determine whether or not they believe a given land use action will exacerbate or relieve displacement pressures given this context.

To determine whether or not the legislation was followed in our case studies, we did a qualitative examination of written RERs as compared to what the law requires, and noted if RERs addressed non-required topics and considerations. To determine if RERs affected the decisionmaking process, we looked at whether the land use proposal was modified between certification and passage, and if the modification could be traced at least in part to disclosures or discussions the RER raised.

To determine whether an RER informed the public debate, we began by identifying the relevant media articles and planning/environmental/public review artifacts, such as environmental impact or assessment statements, City Planning Commission and Landmarks Preservation Commission reports, City Council hearing recordings and transcripts, adopted resolutions, and the RER itself. These were primarily found via Google News, Community Board websites, the Department of City Planning’s Zoning Application Portal (ZAP), the City Council’s Legistar portal, and the Department and Council’s respective YouTube channels. Analyzing these allowed us to develop a qualitative profile of each case study and identify relevant content to address our research questions.

To provide a richer evidence base, we conducted a quantitative analysis of themes discussed across the above media coverage, hearings, and documents during each development’s public review process. We chose themes that included plain English terms that we expected to be familiar and of interest to laypeople (e.g., “affordability,” “opportunity”), as well as specific terms relating to legislation and official programs of interest (e.g., “racial equity report,” “mandatory inclusionary housing”). Each theme included a number of keywords to capture a range of how the theme might be referenced in text and speech. We then ran a text analysis script in the programming language Python, which counted the number of times each theme was mentioned at each stage of the public review process for each case study. The theme definition and counts are available in the Appendix.

It is important to note that this analysis does not capture the context in which a particular theme is mentioned, and that different themes might have different meanings depending on the speaker, audience, and other factors. A longtime tenant in a gentrifying neighborhood referencing “affordability” is likely speaking in a different context than a newer homeowner. Someone talking to a predominantly Black audience may not have to reference themes of race and equity as explicitly as when talking to a predominantly white audience. In addition, the identity of a speaker, or the constituency they represent, could also imply a reference to themes not specifically mentioned. For instance, a tenant union expressing concerns about affordability could easily be seen to be addressing themes of displacement as well, even if not explicitly mentioned.

Neighborhood-scale rezoning (Queens, New York)

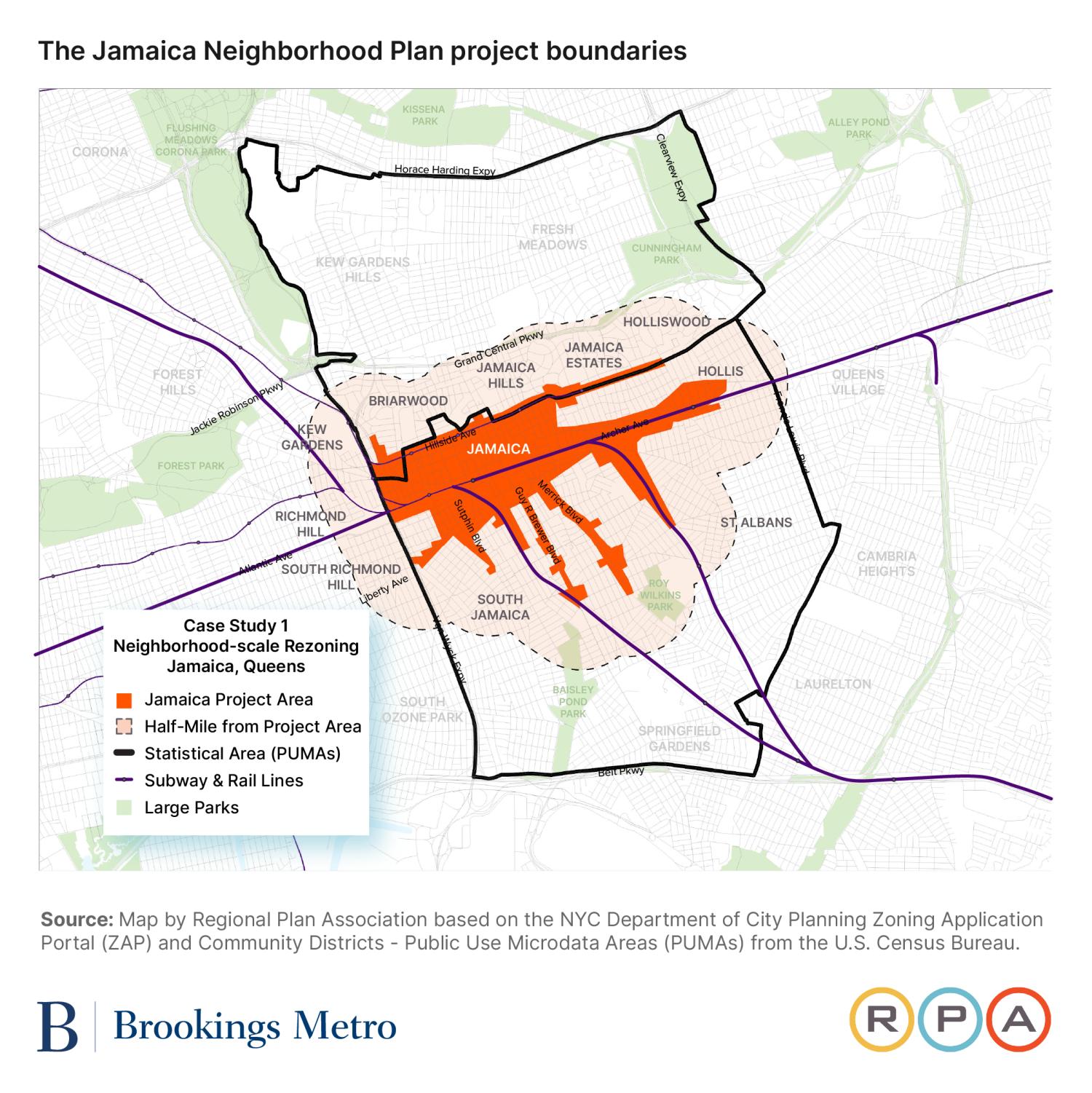

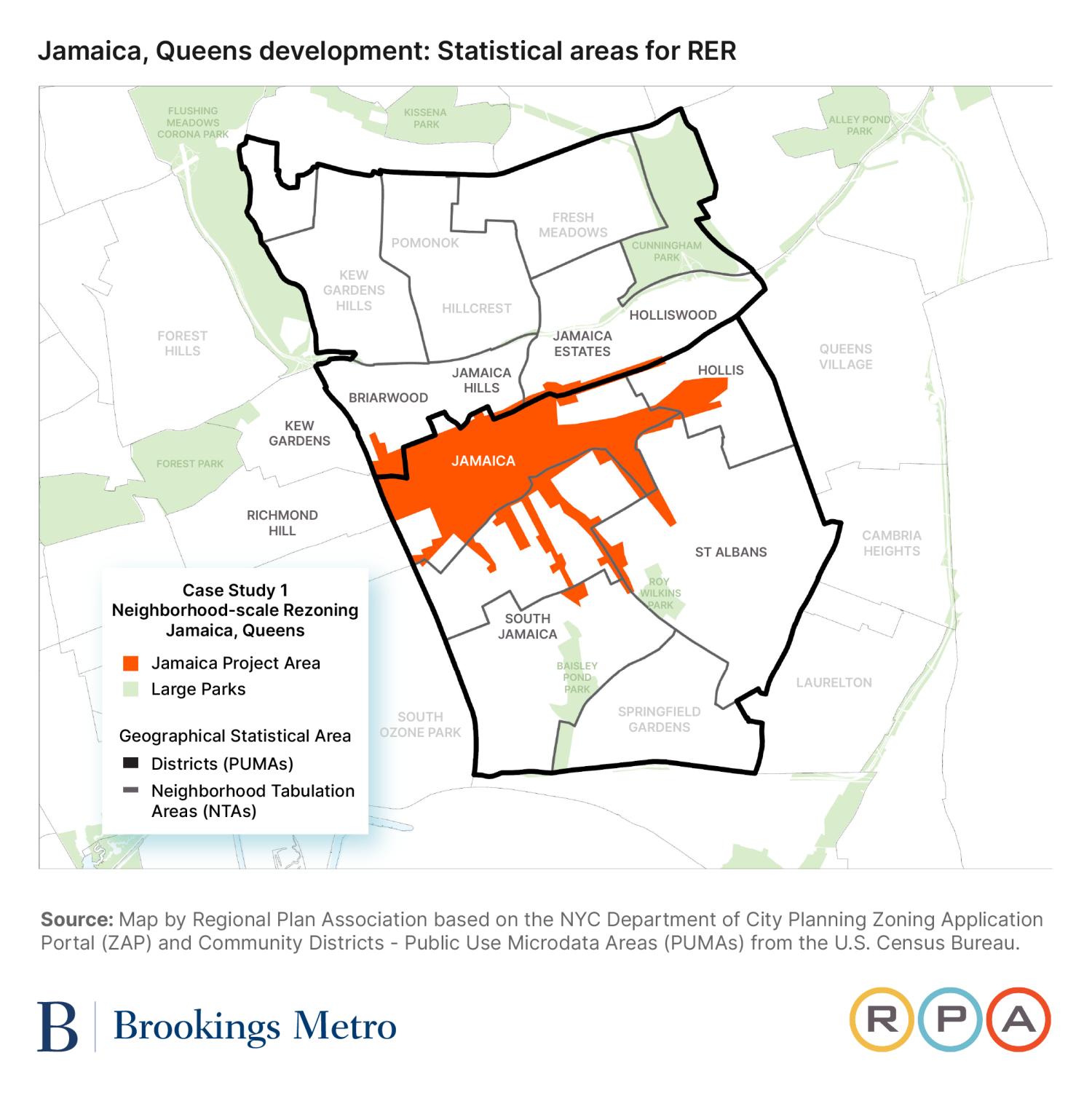

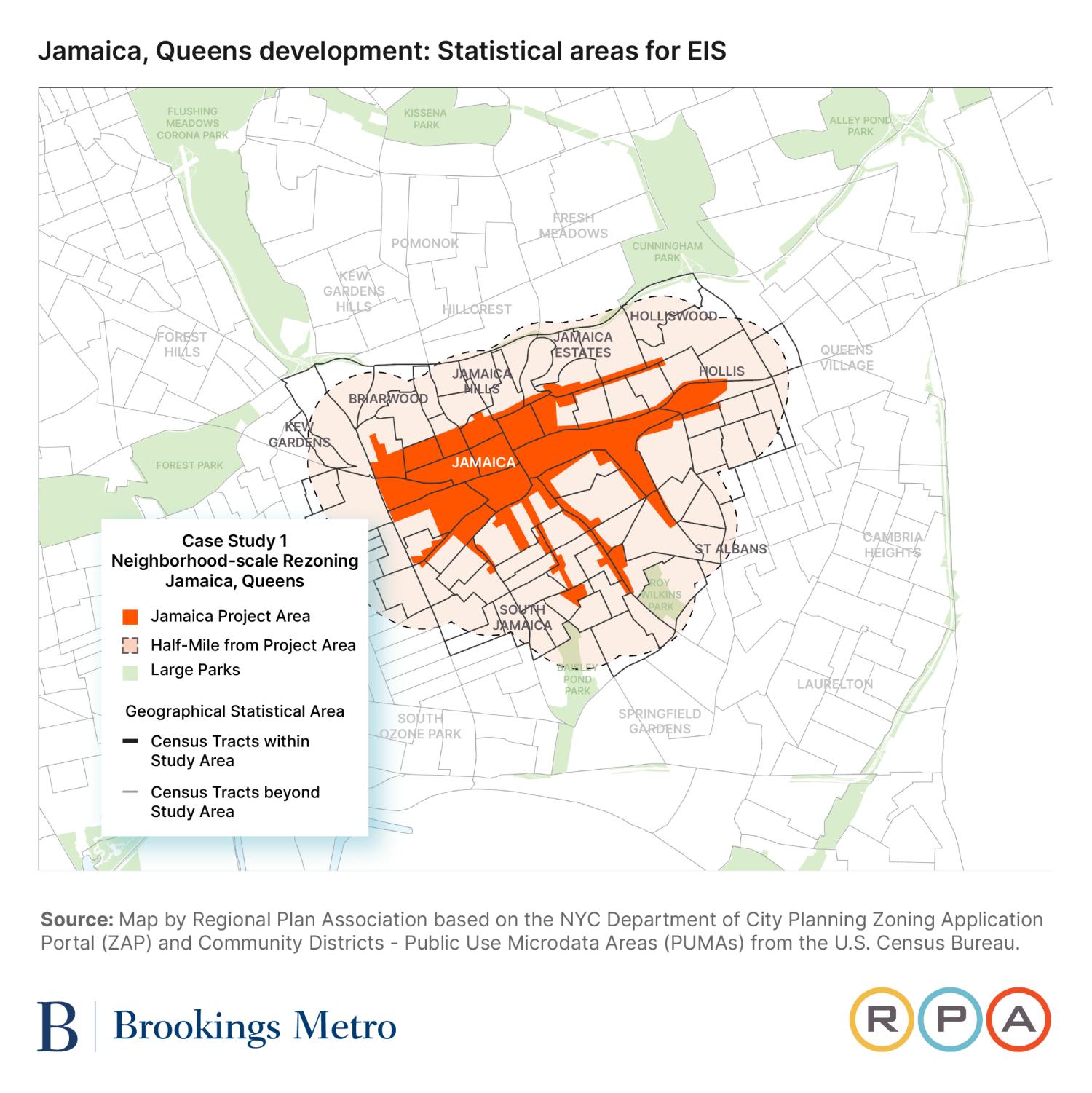

Our first case study is a major city-led neighborhood upzoning initiated in 2025 in the borough of Queens, known as the Jamaica Neighborhood Plan. We analyze the impact and influence of RERs within the context of this large-scale, development-oriented land use proposal in a middle-class, majority-Black neighborhood.2

The Jamaica Neighborhood Plan seeks to create over 12,000 new residential units, around one-third of which will be income-restricted. In addition, the plan will create over 2 million square feet of commercial uses and community facilities, as well as more than 7,000 jobs.

This plan is currently going through New York’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure (ULURP), which requires several hearings and two votes before being approved. While not every land use action that triggers an RER also triggers a ULURP (and vice versa), the overlap is considerable. There is also some overlap between what is required from the environmental review process that ULURP triggers and an RER.

Geographically, the study area covers Downtown Jamaica, the railway corridor to the east, and along several transit-rich road corridors to the south. By the standards of rezonings or other land use actions in New York, this is an extremely large area with a high diversity of land uses, leading to a complicated proposal and resulting EIS. Related zoning actions will map the largest Mandatory Inclusionary Housing (MIH) area in the city. In terms of displacement risk, different Neighborhood Tabulation Areas (NTAs) that overlap with the rezoning area range from “Higher” (the second-highest displacement risk designation) to “Lower” (the second-lowest displacement risk designation), with the majority of the rezoning being in the “Jamaica” NTA, which has a “Higher” designation.3

From a usability standpoint, the project’s RER is long (156 pages) and dense. Nearly 75% of that length—the last 116 pages—is devoted to what decisionmaking experts call a “data dump”: printouts of the relevant American Community Survey (ACS) data of representative Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs). This data compilation, while coherent, is not formatted or summarized to easily inform readers, and is easily accessible elsewhere in more digestible formats. It is clear that the purpose of its inclusion is to meet basic requirements—i.e., fulfill the letter of the law. Indeed, all RERs have a similar data compilation.

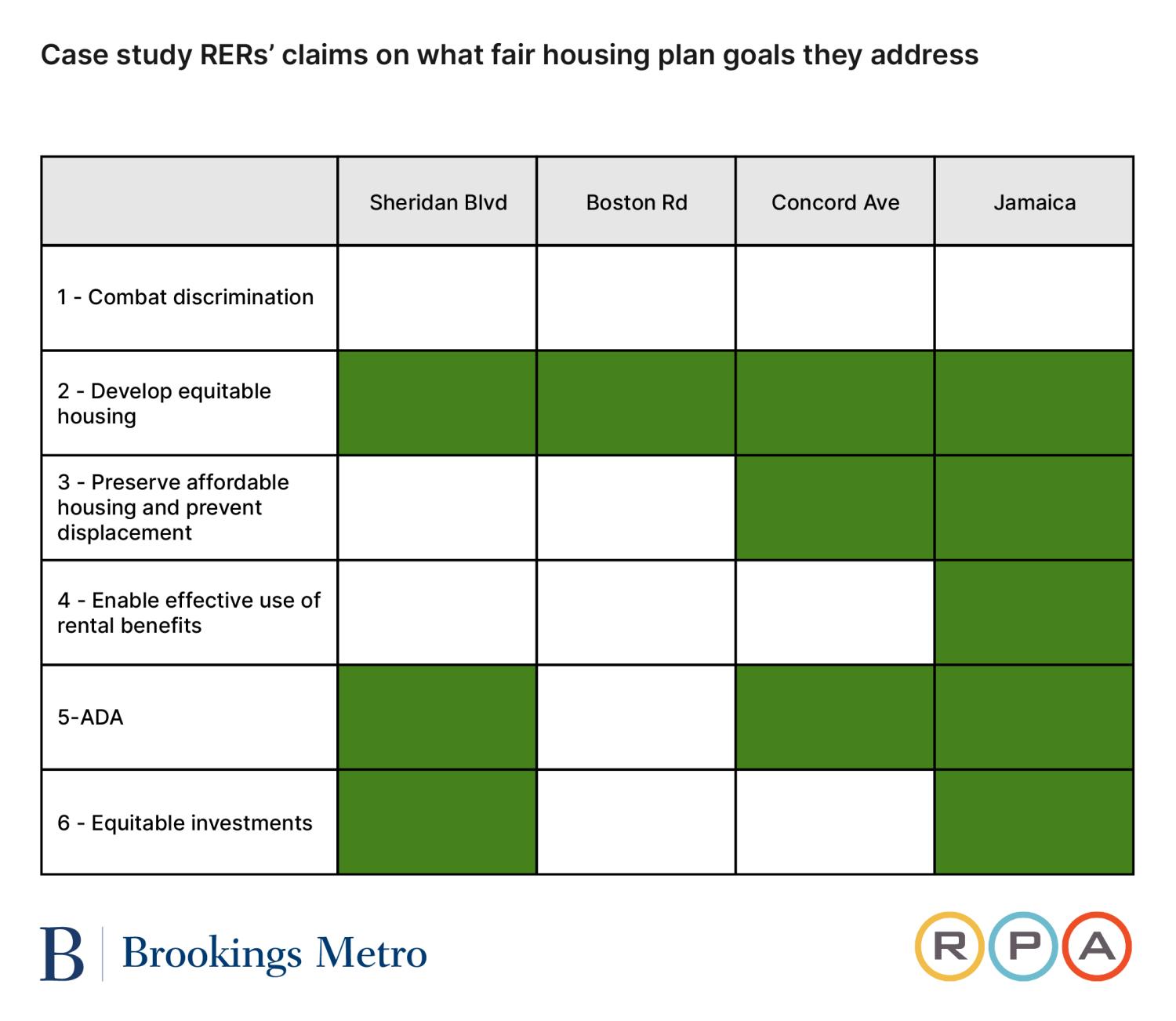

The main report, however, offers more. The elements that the report requires on a formulaic basis—project-specific information on the anticipated residential affordability of new housing units, anticipated new jobs, and estimated construction jobs, as well as community-specific information sourced from the EDDE—are presented in a readable and professional manner. It also contains two more components that contribute to the report: a narrative executive summary and a section on “Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing” (in which the plan is identified as furthering five out of the six goals of Where We Live NYC, the city’s fair housing plan, outlined in the sidebar and table below) and “Promoting Equitable Access to Opportunity.” While the legislation requires both of these components, those requirements are more narrative and less prescriptive, and as such, have the potential for more differences in quality. Here, both sections are thorough and, notably, go somewhat beyond what is strictly required. The report does have some copyediting mistakes, such as repeating one section, but overall it is a quality and professional product.

Where We Live NYC fair housing plan goals

- Fight discrimination and ensure equal access to housing.

- Build more housing in all neighborhoods across New York City and the region.

- Protect existing affordable housing and prevent displacement.

- Ensure access to different types of neighborhoods for tenants using housing vouchers.

- Expand and improve housing options and accommodations for people with disabilities.

- Improve conditions, services, and infrastructure in historically disinvested neighborhoods.

Informing the public debate

There is a great deal of both media mentions and public discussion around this rezoning, which is perhaps not surprising given its status as a large-scale, city-sponsored land use initiative across a broad geography.

Almost all media articles about the Jamaica Neighborhood Plan discuss affordability and opportunity, as have each of the public review stages to date.4 In the two-hour-long borough president hearing dedicated to the plan, “opportunity” was mentioned 42 times and “affordability” 66 times. In two hours and 25 minutes of public testimony on the plan at the City Planning Commission, “opportunity” was mentioned 33 times and “affordability” 89 times. This is a good deal more than the themes of “equity,” “race,” and “displacement” that RERs are meant to directly address, which were referenced a combined 31, 25, and 23 times, respectively, in both hearings (total references for each hearing are in the Appendix).

Despite these thematic references to affordability, opportunity, race, and displacement, explicit references to the RER were notably absent from media articles and the public review process to date. It is possible that people are referencing data from the RER while not attributing the source. However, it appears likely that while community stakeholders and the media will readily engage with these topics, they are not necessarily leveraging RERs as an evidence base to support their efforts.

Costs and benefits to the community were a major topic of discussion at City Planning Commission (CPC) and City Council hearings. At the City Council hearing, council members representing the area sought guarantees from city agencies that the design and implementation of the plan would meet the needs of existing residents. Their primary issues of concern—transportation, sewage capacity, and schools—are all issues covered by the project’s EIS, not its RER. In fact, race and equity were scarcely mentioned at all during the three-hour hearing.

After the hearing but before the subcommittee vote, a City Council member who represents the area wrote an editorial outlining her concerns as well as concerns she had heard from the community. While both equity and affordable housing were mentioned (along with many other infrastructure concerns such as stormwater management, school capacity, and open space), the RER and EDDE were not referenced, nor was race in general.

Changes to project scope

The CPC made minor adjustments to the plan, including amending the project’s overarching goals to include a clearer focus on mixed-use and transit-oriented development as growth engines. The previous goal to “encourage the development of affordable housing” was replaced with “broadening the range of housing choices at varied incomes.” Other changes modified parking and loading requirements, incentivized more public plazas, and adjusted some height and bulk regulations, but the plan passed largely intact in August 2025. While there were no stated reasons for these adjustments, none were germane to subjects the RER directly addressed. It should be noted that two commissioners voted against the proposal, with one citing affordability concerns as the reason.

The New York City Council Committee on Land Use made other adjustments to the plan. These were mostly minor geographic and zoning changes that served to slightly reduce the allowed density. One more significant change was the requirement to only map MIH options 1 and 3, which provide for the deepest affordability, in certain areas. The Council also secured several funding commitments, mainly in the realm of infrastructure improvements, from the Adams mayoral administration as part of the agreement to pass the rezoning.

Developer-led projects (Bronx, New York)

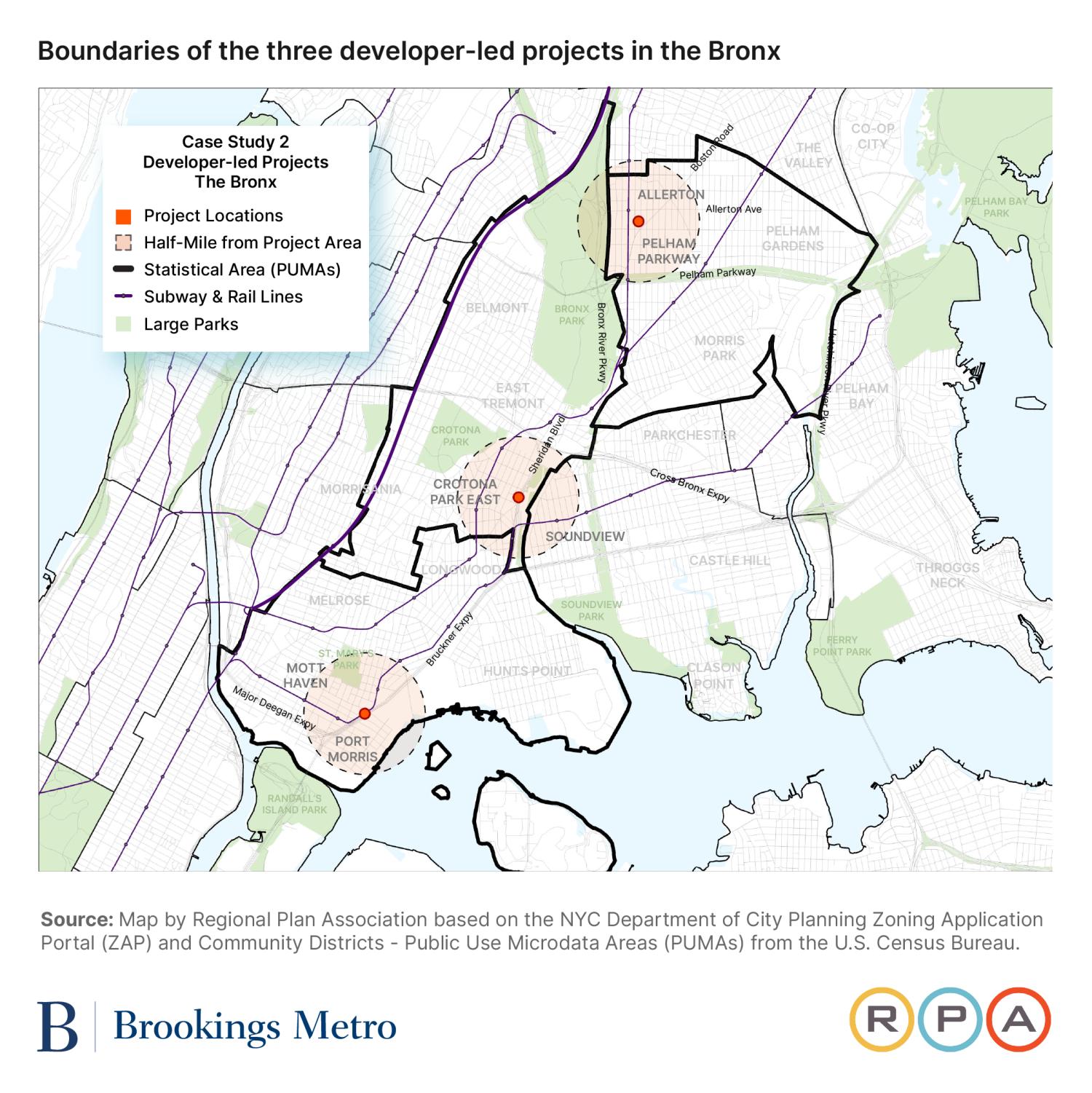

This case study includes three distinct private applications in the Bronx (i.e., applications for land use changes by individual developers, not the city), all of which are in lower-income, majority-Latino or Hispanic neighborhoods. At the time of application, all three projects were within the “highest” displacement risk areas, as identified by the EDDE.5 All three developments were approved by both the CPC and the City Council, and took effect between May 2023 and February 2025.

Project A: 1460-1480 Sheridan Boulevard

Sheridan Boulevard is a planned development of 970 dwelling units, led by Bronx-based applicant Simone Development Companies. All units in the building are proposed to be income-restricted, with 60% of units at 80% area median income (AMI) or lower, and 40% of units between 80% and 120% AMI, in line with the Department of Housing Preservation and Development’s (HPD) Mix & Match program. A mix of studio, one-bedroom, two-bedroom, and three-bedroom units are planned. The project received a conditional favorable rating at both the community board and borough president stages of ULURP, and was approved by both the CPC and City Council in August and September 2023, respectively.

The project’s RER was prepared by external consultant Langan, an environmental and engineering consulting firm. Sheridan Boulevard’s RER complies with the city’s legislated requirements. The required quantitative components on project-specific and community profile information are present. Langan goes slightly beyond the letter of the law by providing additional detail on estimated job creation, which is not required on the basis that the nonresidential tenants are yet unknown.

The RER’s more qualitative executive summary and narrative statement are prepared competently, with the commentary corresponding to the guidance set out in the city’s submission guide. The project’s contribution to three specific goals of Where We Live NYC, the city’s plan for affirmatively furthering fair housing, are clearly identified.6 As with RERs from other case studies, there was a specific focus on historic rates of housing production in the area (based on PUMA boundaries).

As the project was large enough to trigger an EIS, its RER can be read in conjunction with the full “Socioeconomic Conditions” chapter from that report.

Informing the public debate

The public debate around this project focused more on the specifics of the development—particularly, the unit sizes—rather than the broader themes addressed in the RER or the RER itself.

The RER was only explicitly referenced at one stage of the public review (ULURP) process for this application: At the CPC’s public hearing, two individuals mentioned the RER, both in the context of comparing the area’s median rent and the project’s proposed affordability. The individuals were an advocate from a local community-based organization (the Bronx River Alliance) and a CPC commissioner who lives in the area.

At the same time, a range of stakeholders referenced words and phrases related to affordability and opportunity throughout the development’s public review process. In a pre-hearing presentation, the applicant presented a slide on preliminary AMI and unit breakdowns in response to a question. At the CPC hearing, a resident testified that the proposed affordability and rent levels are above the AMIs and rents of current area residents.

Direct discussion of displacement and gentrification was not prevalent in the development’s public review process, only being mentioned in one media article and by three people in public testimony.

There was a consistent focus on the breakdown of unit types in the Sheridan Boulevard development (i.e., the split between studio and one-bedroom apartments versus larger apartments more suitable for families) in public discussion. As discussed by the Bronx borough president in their recommendation, the availability of units appropriate for families affects the ability of households to remain in their communities as their families grow, essentially representing a future displacement risk.

The rarity of references to race is also noteworthy. It may be the case that explicit consideration of race (using terms such as “Black,” “Hispanic,” “Latino,” “African American,” “minorities,” etc.) has been set aside in favor of talking more broadly about the residents or the community, which is itself diverse. In the area around the Sheridan Boulevard development, 60% of residents are Latino or Hispanic and 33% are Black. In this sense, any discussion of affordability for current residents is implicitly a discussion about race.

Changes to project scope

Proposed unit numbers and affordability breakdowns for Sheridan Boulevard did not change over the course of the public review process, based on an analysis of the project’s design at various key stages of ULURP. This suggests that despite the prevalence of affordability as a concern and scattered references to the RER, neither was influential in changing the outcome of the development’s size or affordability breakdown.

Project B: 2560 Boston Road

The Boston Road development is led by Slate Property Group. All but one of its 333 dwelling units are income-restricted, with bands between 30% AMI and 80% AMI.

Slate Property Group prepared the project’s RER. Due to Boston Road being a smaller project, it did not trigger a full EIS review. Nonetheless, Boston Road’s RER is similar in quality, compliance, and coverage to Sheridan Boulevard’s RER. The main difference is that the Boston Road project only declares a contribution to one goal under Where We Live NYC: the development of equitable housing, which all other case studies declared their project contributed to as well.

Informing the public debate

The public debate around this project focused more on the broader themes the RER was meant to be address (particularly, residential displacement), although again specific references to the RER were rare.

From the outset of the public review process (the community board stage of ULURP), community members voiced concerns about the development. A letter signed by the chair of Bronx Community Board 11 explained that the board voted to disapprove the development proposal (27 were against the proposal, one in favor, and three abstained), on the grounds that existing residents may be displaced. The letter cited evidence from the EAS that household incomes in the “Proposed Project” would be at least 43% higher than existing incomes. Also cited were data from the EDDE that showed the displacement risk for the development’s area was rated as “highest.” Several members of Bronx Community Board 11 had input into the inclusion of displacement risk in the letter during the board meeting, including whether to specifically mention direct and/or indirect forms of displacement.

Frequent references to displacement continued at the CPC and City Council stages of the public review process. However, these primarily came from two new voices—in particular, a community advocate (and founder of the community-based organization Friends of Pelham Parkway), who was dominant in discussing the development’s displacement-related risks.7 This was the same community advocate who referenced the RER and EDDE in their testimony, and in the one media article that references the RER. This contrasts with the public review process for the Sheridan Road development, where displacement was not frequently mentioned despite it being a similarly 100% income-restricted development.8

Changes to project scope

As with the Sheridan Boulevard project, the overall size of the Boston Road development did not change throughout the public review process. The number of affordable units proposed remained at 332 from certification through to the approved resolution by the City Council.

What did change were the affordability bands and the number of units available at each AMI level, although the average AMI level for the affordable units did not change. Between the disclosure of the RER report on September 1, 2022 and a letter the developer sent to Bronx Community Board 11 on January 25, 2023, the percentage of units available at 50% AMI or below increased from 50% to 60%. However, the 50% of units allocated to the 51% to 80% AMI tier in the RER were shifted to the 90% AMI level in the January 2023 letter. In other words, some of the units became less affordable. The updated AMI level proposals, made under HPD’s Mix & Match program, were maintained in the commitments made to City Council.

Notably, the proposed affordability levels (based on the selection of MIH options) appeared to not be locked in even by the time of the first City Council hearing on April 19, 2023. A representative of the applicant testified that the zoning text amendment would require permanent affordability under either MIH Option 1 or 2. The specific choice between Option 1 and 2 entails a tradeoff between the number of affordable units and their designated affordability level. The applicant’s testimony struck an educational tone on the available HPD subsidies—namely, Mix & Match and ELLA (Extremely Low and Low-Income Affordability). This potentially points to constraints placed on feasible affordability levels as a result of HPD’s terms sheets.

Project C: 438 Concord Avenue

The development at Concord Avenue is the smallest of the three case studies, with 87 total proposed dwelling units. Of these, 24 are expected to be affordable at an average of 60% AMI. The applicant is BronxCo, LLC.

Concord Avenue’s RER was prepared by GZA GeoEnvironmental. Its preparation is broadly similar to the other private case studies, although Section 2.2 on nonresidential space and jobs is blank (this is still compliant, assuming that the future tenants are unknown). A departure from the other two private case studies is that the Concord Avenue development also identifies a contribution to the third goal of Where We Live NYC, which seeks to preserve affordable housing and prevent the displacement of existing residents.

Informing the public debate

We did not find any media mentions related to this application. Public comment did not reference the RER at all, although there were frequent references to affordability.

Similar to the Boston Road case, there were objections to the development from the outset of the public review process. In the Bronx Community Board 1 vote to disapprove of the project, a majority of voting members (19 of 24) stipulated a condition regarding the “inclusion of 20%-30% AMI for units.” It is clear that the board had concerns over the affordability of the development for area residents. While the borough president acknowledged these affordability concerns in their recommendation, it was noted that deepening the development’s affordability profile may come at the expense of other co-benefits, including family-sized units and job creation.

It is relevant to note that no community stakeholder mentioned the RER, the EDDE, or any other long-standing form of evidence, such as census data.

Changes to project scope

In contrast to both the Sheridan Boulevard and Boston Road cases, the Concord Avenue project was ultimately modified to require the developer to deepen the overall affordability profile of the building. At the first City Council hearing for the development, the applicant acknowledged that both MIH Options 1 and 2 were being mapped, although the intent was to use Option 1. Note that Option 2 has more affordable units (30% versus 25%), albeit at a higher AMI level (80% instead of 60%). When the Concord Avenue development was heard at the City Council subcommittee for a second time, the council recommended that MIH Option 2 be removed and the “Deep Affordability Option” be added. This recommendation was approved by the CPC and adopted by the City Council.

Given that the Deep Affordability Option mandates 20% of the units be affordable at 40% of AMI, the modification goes some of the way toward addressing the affordability concerns the Community Board raised. However, it is unclear to what extent (if any) the Community Board’s feedback prompted the City Council modifications. The only reference to motivation comes from the hearing transcript for the second City Council subcommittee hearing, which stated that “Deputy Speaker Ayala supports this proposal based on the recommended modifications.” Potentially, this alludes to the influence of the local council member, part of a long-standing practice known as “council member deference.”9

Historic District designation (Brooklyn, New York)

Racial equity reports not only apply to proposed zoning actions, but also to Historic District designations that affect all or some of at least four city blocks.

One consideration when looking at the intersection between land use actions and racial equity is that because of the dynamic nature of cities, the lack of development can have just as much effect on racial equity as development itself. However, the nature of the legislation is such that RERs are only triggered by an “action” scenario.

There are certain things that mitigate this consideration in New York’s context. One is that the EDDE data tool is publicly available citywide, enabling people to measure displacement risk both for neighborhoods that are undergoing a land use action and those that aren’t. Another is that not all “actions” lead to development. Indeed, some—such as contextual zoning, down-zonings, and Historic District designations—have the effect of slowing or stopping development that would otherwise occur. That these also trigger an RER keeps the legislation from focusing solely on the intersection of development and displacement, and instead allow it to explore a wider range of relationships between land use and racial equity.

Since the legislation was passed, there have been no Historic District designations or proposals that have been large enough to trigger an RER. This is not a surprise, as the current mayoral administration has been explicitly pro-growth, and because large Historic District designations have the effect of constraining rather than encouraging housing growth, these designations would likely run counter to current public policy. However, as we posit later, another reason for this may be the RER legislation itself.

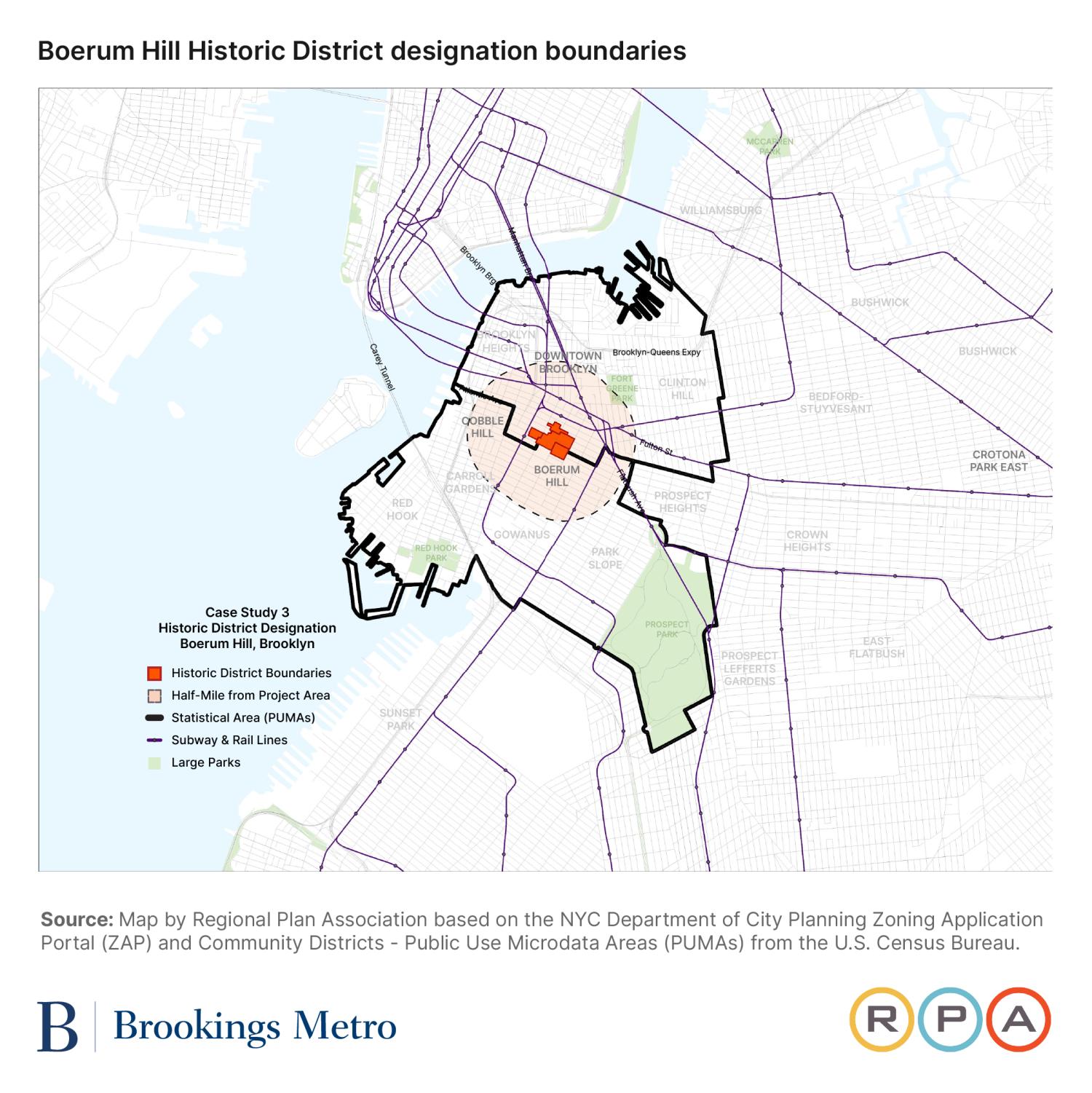

While there have been more recent Historic District designations, we are studying the Boerum Hill Historic District designation as the most recent designation that took place in a majority-white and higher-income neighborhood, giving us a contrast not only of action type, but also of demographics against our other two case studies.

The Boerum Hill Historic District Extension was approved in June 2018. It encompasses 288 buildings over all or parts of seven census blocks in three distinct areas adjacent to the existing Boerum Hill Historic District. All of these are in a single neighborhood (although split between two NTAs) in Northwest Brooklyn. This neighborhood has undergone considerable gentrification in recent decades, and as of the 2020 census, is a majority-white and higher-income neighborhood.10 It is split between two NTAs; the EDDE rates one NTA’s displacement risk as “intermediate” and other “low.”11

Informing the public debate

Newspaper articles on the Boerum Hill Historic District designation mainly focused on the architecture and historic character of the neighborhood, with only two mentions of “race,” two of “affordability,” and one each of “cost” and “opportunity.” However, the official press release as well as the Historic District Designation Report itself referenced race more often and directly, although mainly in the context of the history of the neighborhood as opposed to its current conditions.

During public testimony at the designation hearing, there were no references from any commentators to the current racial or other demographics of the neighborhood.12 There were also no comments referencing affordability or displacement concerns, although concerns over renovation costs by building owners as well as commercial rents and tenants were strong themes. The only germane comment was from one commentator who noted that a local Historic District designation would help with a similar state designation, which would then allow any low- or moderate-income census tracts within its boundaries to be eligible to receive state historic tax credits. Since there is not currently any disclosure required as to whether or not such census tracts might exist within a proposed Historic District, this could be a good addition to any RER a proposed Historic District designation triggers. Although not strictly required by the letter of the law, this would not be hard to include, and could even be easily added to the community profiles available for download from the EDDE.

As can be expected of a Historic District hearing, the conversation mainly focused on architecture and neighborhood character. Most opposition to the designation was from commercial or mixed-use building owners, who expressed concern about potential added expenses for renovations. Most support came from residential owners or professional preservationists, who noted the neighborhood’s appropriate architectural character for Historic District designation.

However, there were two references, both from professional preservation organizations in support of the designation, to the history of the neighborhood as the home of a former Mohawk community. The Mohawk, or Kanien’kehá:ka, people are part of an Indigenous, Iroquois-speaking nation native to Upstate New York and Quebec, many of whom migrated to Brooklyn in the early- and mid-20th century and were mainly employed as ironworkers.13 This was reflected in the description of a former church (converted to housing in the 1980s), union hall, and bar in the district as community hubs for the former Mohawk population. It should be noted that as of the 2020 census, there is virtually no Mohawk community in the area, with the six NTAs representing the one that encompasses the Historic District and the five that are adjacent reporting only 103 people with American Indian ancestry out of a population of over 215,000.

The Historic District Designation Report also recognized this history, along with the district’s history of Puerto Rican, Syrian, African American, and European communities. The report also made note of the history and effects of redlining, housing discrimination, and urban renewal. Indeed, this Historic District report had a more comprehensive racial and ethnic historiography of the neighborhood than any of the RERs we studied.

While it would be a stretch to say that this history informed the proposal to designate this area as a Historic District, the report did note that “the diverse cultural and economic history of Boerum Hill, as well as its largely intact 19th century architectural fabric, all contribute to the neighborhood’s character and sense of place.” The proposal was not modified between the hearing and designation and was adopted as proposed.

This Historic District designation is a case in which an RER may have added significantly to the public conversation, especially in quantifying how the designation would further any of the city’s six fair housing goals under Where We Live NYC. While it is not surprising to expect a Historic District designation to focus on history, these designations also take place within the context of the current neighborhood and affect its future. Yet there was virtually no public discussion of the intersection of this designation with housing, development, affordability, displacement, or racial equity. In fact, the effect designation may have on restricting development was not raised at all in either the designation report or by any of the commentators.

Despite the fact that no RERs have been conducted yet on Historic District designation proposals, even just the passage of the legislation itself may have already had an effect. The fact that these questions would need to be grappled with, or at least raised, when discussing the appropriateness of a Historic District designation might well inform the unwillingness to pursue designations that may trigger them.

Discussion

Racial equity reports differ significantly from other major reports that are required before a land use action can be certified—namely, an environmental impact or assessment statement. These are specifically meant to be predictive, even though the certainty with which effects can be predicted accurately ranges considerably. The RER is not meant to be predictive, instead providing a snapshot of relevant information at the neighborhood level for the current point in time.

An EIS, for example, tells you exactly what shadows a development will cast and where; it does not tell you if the neighborhood the development is located in is one of the sunnier or shadier neighborhoods in the city. It tells you how many additional automobile trips a new building is expected to produce; it does not tell you if the neighborhood sees more or fewer auto crashes than average. An EIS even addresses a main topic of RERs—displacement—by predicting both direct and indirect residential and commercial displacement. But it does not tell you the “displacement risk” of a neighborhood like the EDDE does.

Both the “informational” approach of an RER and the “predictive” approach of an EIS have value. It is an open argument as to which approach is more appropriate to employ when it comes to racial equity (or other topics)—and perhaps the answer is that both should be used. However, it should be noted that there are significant obstacles to implementing a predictive model when it comes to RERs.

This difficulty starts with the EDDE. Displacement in the EDDE it is not directly measured, but instead the result of a subjectively developed index that takes into account several different data points. And while some research has been conducted on some of the individual data points that make up this index and their relationship to observed displacement (including by our organization, Regional Plan Association), the EDDE’s index itself has never been tested methodologically against actual observed displacement.14

“Displacement” itself is also a subjective term that can be defined several different ways, with the ability to accurately observe it varying depending on this definition. And because the RER legislation has only been in effect since 2022, even if there was the desire for the EDDE to function as a predictive tool, there is not yet the ability to conduct a longitudinal study on its ability to accurately predict displacement effects.15 Even if all of this could be quantified, there is then the additional step of examining the racialized effect of this displacement.

Compared to other cities in the United States, New York has an extremely high degree of racial and ethnic diversity (although not integration), as well as a high degree of diversity within each major racial and ethnic group in terms of income, religion, political leanings, housing tenure, immigration, citizenship status, and many other factors. It also has a very high degree of land use diversity, both existing and potentially allowed, ranging from the densest residential areas in the country to districts that look similar to the average American exurb. The intersection of these leads to an almost infinite number of permutations when it comes to the intersections between land use changes and race, each with their own particular considerations.

This is not to say that employing only an informational model does not have significant weaknesses. Foremost among these is that by providing no information or reference as to the effects of a possible land use change on racialized displacement, it is possible, or even expected, that all parties will note that the information the RER and EDDE provide supports their preferred outcome. One person can argue that racial equity or displacement concerns mean an action should be taken, while another can argue that the exact same concerns mean that the same action should not be taken.

The RER does require an applicant to illustrate how a land use action will impact the six goals of Where We Live NYC, which can be taken as predictive rather than simply informative. However, this is a narrative section that does not require any specific data be provided or methodology employed to uphold the conclusions; in essence, an applicant can simply assert that their project will (or will not) meet these goals. It is informative that the most direct reference to an RER that was found in public testimony in these case studies was used to argue against the development of low, very low, and extremely low-income housing on the grounds that it would exacerbate displacement. It is also informative that similar projects claimed to address different fair housing goals. The Sheridan Boulevard case, for instance, claimed to address three of the goals while the Boston Road case only claimed to address one, despite them both being 100% affordable developments of similar AMIs in similar neighborhoods with the same “displacement risk” rating from the EDDE.

The quality and appropriateness of the overall structure of New York’s RERs, and how well they are designed to address racial equity, is another open discussion. Since Brookings has developed a rubric for “best practices” to evaluate racial equity impact assessments (REIAs), we can compare New York’s RERs against this rubric. Brookings outlines five specific considerations; the RERs, in general, meet all of these considerations at least somewhat, but don’t meet any of them fully. We illustrate the specifics of how RERs compare to Brookings’ rubric in the following sections.

Consideration #1: Core concepts—Is risk well defined? Are the data and methods used specific and credible?

In New York RERs, “risk” is mainly measured in potential displacement as a metric. “Displacement” is defined in the EDDE as “the level of risk residents face of being unable to remain in their homes or neighborhoods,” a definition that is vague enough to beg several questions. For instance, how much weight is given to “home” versus “neighborhood?” A common situation in New York is that a family has a stable housing situation through rent stabilization, homeownership, or subsidized housing, but cannot afford to move to a larger unit in the same neighborhood when their family grows. Would this be considered “displacement” under this definition?

The data involved in both RERs and the EDDE is specific and ultimately comes from credible sources, mainly the American Community Survey (ACS). However, the methods are more questionable. As discussed above, the displacement risk index the EDDE provides is not tested against any actual objective measures of displacement and, as such, cannot be relied on to provide an accurate measure of displacement risk. As recommended below, the EDDE should make note of this and provide a disclaimer until it is tested and a correlation demonstrated.

Consideration #2: Reference groups—Are the groups and protected characteristics that the RER analyzes appropriate to the proposal? Is the evidence used in the RER applicable to these groups?

The main body of an RER provides data on a summarized and standardized set of community indicators (race and ethnicity, household income, labor force participation, and high school graduation rates), disaggregated by race. All RERs contain the same quantitative community data.

Such data enable the reader to contextualize the demographic composition of the neighborhood that a particular development is situated in. Readers are able to examine how outcomes vary between different racial groups in a community—for example, whether there are disparities in household incomes between white, Latino or Hispanic, Black, and Asian American residents.

In effect, the Community Profile and its summary provide an assessment of the community’s existing conditions and outcomes through a racial lens. The focus on “existing” conditions is crucial. The standardized data presented are a static representation of the community, and do not consider the future impacts on the community as a result of a development project proceeding.

There are three project-specific sections of an RER that could be used to indicate the potential impacts of a development on defined reference groups such as a racial group, although some of these data need to be inferred.

First, in the “description of project components,” RERs outline the number of units proposed at each affordability band (based on AMI). It also states the planned square footage of residential and nonresidential uses, as well as the estimated number of jobs to be created by construction and the nonresidential uses.

For example, in the case of the private application at 1460-1480 Sheridan Boulevard in the Bronx, all 970 proposed units are shown to have an “affordable” (i.e., income-restricted) designation. Of these 970 units, 146 (15%) are designated as affordable to those earning 0% to 30% of AMI. According to the community profile data provided in Section 3 of the RER, an estimated 45% to 50% of Asian American, Latino or Hispanic, and Black households in the area were in this 0% to 30% AMI band in 2015‐19.16 Although the RER does not explicitly make this connection, linking these two pieces of information leads to the conclusion that nearly half of the community’s nonwhite population would be unable to access the vast majority of units in the development.

The two narrative components in an RER (the executive summary and the narrative statement on affirmatively furthering fair housing) give applicants the opportunity to discuss their project in their own words. Guidelines for both sections are brief, although they include a background on the Where We Live NYC plan to support the applicant in framing how their application affirmatively furthers fair housing.

As they stand, the narrative sections are declarative in nature and represent the applicant’s own opinion about the merits of their project. There is effectively no quality control on the narrative statements and no baseline to benchmark its claims against. However, this may change with the planned October 2025 implementation of the city’s new fair housing plan, which mandates the development of quantitative housing production targets for each community district.

Consideration #3: Framing of the policy choice and benchmark—Does the RER analyze the ‘no action’ alternative in addition to the proposed policy change?

The city’s submission guide for RERs does not request applicants to provide an analysis of a “no action” alternative to the development. This is perhaps not surprising, as requirements to analyze an “action” scenario itself are minimal. However, an analysis of a “no action” (and action) condition, including its effects on displacement, will sometimes be available in the project’s EIS or EAS depending on project scope, although there is not a specific racial lens to these analyses.

In the cases of the privately led Sheridan Boulevard and Boston Road developments, the respective project EIS/EAS concludes that the proposed development would introduce a resident population with higher median incomes than existing households. In both cases, the incremental population increase versus the no-action scenario does not exceed the 5% increment that would trigger a fuller local real estate market analysis to quantify displacement risk. The Concord Avenue project was too small to even trigger a socioeconomic conditions assessment, even within the EAS.

The Jamaica Neighborhood Plan did, however, trigger a full assessment of indirect residential displacement, including detailed analyses of a no-action scenario and with-action scenario, as part of its EAS.

If available, the socioeconomic analysis in the EIS/EAS could be read as a companion to the RER. However, the need to interpret (and have awareness of) two potentially technical documents may present a burden to a layperson seeking a nuanced but specific determination of an area’s displacement risk with and without new development.

Consideration #4: Evidence—How strong is the evidence base the RER relies upon? Are there multiple sources of analytic evidence, grounded in valid, reliable, and reasonably current data? Are these data available for independent re-analysis? How well does the geography of the data correspond to the geography of the study area?

Because all RERs pull from a transparent and standardized public data source managed by public agencies (the EDDE), data estimates can broadly be considered as valid, reliable, and available for independent re-analysis. The EDDE is also updated on a regular basis and can be considered current. The underlying data also come from multiple sources, although mainly the ACS, and the RER itself does not preclude using other independent data sources as well, although none of the cases we examined did so.

However, when analyzing the geographies RER analysis covers, some spatial issues emerge. Firstly, the default study area of an RER (defined as PUMAs) generally do not match the study areas defined in the EIS/EAS. The EIS/EAS study areas are typically more granular and more reflective of the boundaries of the rezoning area, plus a buffer. This is particularly evident in the case of the Jamaica Neighborhood Plan (see Map 5 and 6).

A secondary issue arises as a result of PUMAs generally being much larger than the relevant rezoning site or area, which is that the “community profile” (based on PUMAs) reported in a project’s RER may not be reflective of the immediate area of the development. Using the case of Jamaica again, the RER reports demographic data on two distinct PUMAs. However, the rezoning area covers only approximately one-quarter of PUMA 4112 and a negligible amount of PUMA 4106 (see Map 5 and 6). More importantly, the data suffer from a statistical bias in spatial data known as the “modifiable areal unit problem.” The rezoning area predominantly covers the Jamaica and South Jamaica NTAs in PUMA 4112, which have a “higher” or “highest” displacement risk. However, the other NTAs in PUMA 4112 have a “lower” displacement risk. Because of the mix of displacement risk levels within PUMA 4112, the community demographics reported are biased toward a lower displacement risk.

Consideration #5: Analysis and interpretation—Are the conclusions of the RER clearly supported by data? Are limitations, including unknowns, spelled out?

Given the “informative” rather than “predictive” nature of New Yorks RERs, the data themselves are often the conclusion. This is specifically the case in the description of the project and neighborhood conditions, although especially in the project description section there are some things (such as job creation numbers) that are less reliable than others (such as unit count). In the narrative sections, conclusions are more qualitative. Here, results are mixed, and whether or not the data support the conclusions becomes more subjective. Each of the case study RERs does make some attempt at a good faith logical case for how their project addresses the various relevant goals of Where We Live NYC, although the quality of these arguments varies and none of them are infallible.

The RERs, on the whole, do not generally caveat their information, spell out limitations, or include unknowns, as is often done in an EIS/EAS. Out of the cases we examined, the Jamaica RER was the most comprehensive when it came to this, sometimes footnoting caveats and limitations, especially in the project-specific information. There is also a helpful graphic explaining margin of error, how it is illustrated in the data charts, and how to properly interpret it included in each of the community profiles that comes with the standard data download from the EDDE.

Findings

Racial equity reports are professionally done, but their quality varies

In our sample, the city-prepared RER for the Jamaica, Queens community met a higher standard than the RERs of privately sponsored project applications in the Bronx.17

All four RERs we examined certainly fulfilled the letter of the law, and since all made heavy use of the EDDE and followed the prescribed format for RERs, there was considerable similarity between them. However, the RER the Department of City Planning (DCP) produced for the Jamaica rezoning is of a higher standard than the three RERs for the private applications in the Bronx. The Jamaica RER provides a more comprehensive and rigorous narrative by referring to a broader set of community statistics and paying closer attention to issues around neighborhood change and displacement risk.

At this still early stage in the implementation of New York’s landmark law requiring RERs, it is difficult to determine what drives quality. Several factors might explain why the Jamaica RER is of a higher standard, for example, than the others we analyzed. That the RER was published in March 2025—almost two years after the city launched the planning effort for the Jamaica Neighborhood Plan—may have contributed. In that time, DCP had the opportunity to clarify the project’s scope and goals as well as interface with myriad stakeholders whose commentary could have shaped the department’s frame of reference for the RER. Moreover, the scale of the 300-block rezoning effort (compared to the much smaller-scale private projects affecting a few city blocks) means that there are more complex issues to address. The level of scrutiny attached to a city-led project of this size puts an onus on DCP to prepare all project documentation to a high standard. DCP’s status as one of the originators of the EDDE tool also means the agency has in-house expertise on how best to use it. Overall operating capacity and experience is also a factor: DCP is a large and well-resourced agency with deep experience leading large-scale land use proposals.

RERs are not often referenced explicitly in media and public testimony

While RERs per se, like other formal land use reports, are rarely referenced explicitly in the public conversation, the issues in RERs are often prime subjects in public debate. While the introduction of the RER legislation was meant to better inform the public debate over the possible racial effects of land use actions, it was that same public debate that itself informed the creation of RERs in 2021. The public debate, and the tools used to inform it, should not be thought of as a simple cause-and-effect either one way or another—instead going hand-in-hand with one reinforcing the other. Indeed, the value of the RER legislation is not just in providing data to inform debate on a single land use proposal—it’s also in how it has advanced the overall conversation on the intersection between land use, displacement, and racial equity.

Still, three years later, it does appear that the debate remains ahead of the tool. Community stakeholders regularly raise issues such as affordability, equity, opportunity, race, and displacement—all of which are focal points of the RER. However, it was rare for community stakeholders to specifically reference the RER or EDDE in their testimony or submissions to the public review process. In our case studies, during public testimony, references just to these five issues outstripped references to the RER or EDDE themselves by a factor 89 to 1.

The few people who did explicitly reference the RER or EDDE were community advocates well versed in interacting with city government. It could be that most members of the public have simply not heard of the EDDE or RERs, or have come across them without understanding how to make use of them. Others may not know of or find value in public reports on land use actions in general. The point applies beyond RERs: Very few people or publications referenced the other city reports meant to provide public information on these major land use actions, such as the environmental impact/assessment statements or the Historic District Designation Report. It is also possible that although there might not be a specific reference to the RER or EDDE in a public comment, the data the RER or EDDE provided is still being referenced.

A central contribution of the RER legislation is requiring a formal, substantive statement around the impact of land use actions on racial equity

Discussion of public policy’s effect on racial equity is far from a given. One of the main impetuses behind the implementation of New York’s RERs was to make sure that this is not the case when it comes to land use actions. This is especially pronounced when it comes to land use actions that have often not triggered these types of discussions, such as Historic District designations. The fact that New York requires an RER does not mean that these discussions are any easier or any more likely to come to a resolution than in cities that do not require similar reports. But it does require the beginning of the conversation and that the topic of race and racial equity be addressed in a formal way. This is a step that should not be discounted—without recognition, no progress can be made.

Does this discussion ultimately impact the proposal? In three of the four projects we analyzed, there were modifications to the affordability levels of the proposed housing, although none changed significantly. While affordability is a major focus of RERs, the lack of direct references to the RER and EDDE by CPC and City Council make it difficult to conclude that they were a defining factor, especially since the prevalence of discussions and modifications around affordability levels in both neighborhood and developer-sponsored rezonings predate the passage of the RER legislation.

The RER requirement to specifically address a proposed land use action’s effect on the six measures of Where We Live NYC, the city’s fair housing plan, is especially valuable. The requirement to illustrate impact on racial equity in a quantitative way strengthens the framework of the required discussion. Again, this does not mean that consensus will be reached or that what is outlined in the RER is undebatable. Its value is simply in further formalizing and quantifying the discussion.

Recommendations

How could New York’s RERs contribute more to the public debate and be used to inform land use decisions more effectively? There are several possibilities, some of which would likely need to be legislatively codified, while others may simply be “best practices” that could be followed and outlined. Our suggestions are as follows:

Provide better education on the availability and usage of RERs

The RER and EDDE tool should be made more visible to the public at every stage of the public review process, with a simple and clear explanation of what they are. Some possible ideas for doing so could be: including a brief description of RERs on hearing notices and written comment submission forms; resources on the DCP website outlining RERs as a source of input for community members to craft their testimonies; and city government partnerships with community-based organizations to provide training sessions. The RER legislation should also be clarified to ensure that RERs for Historic District Designations are submitted and published in advance of the vote on the designation.

The Pratt Center for Community Development has outlined several recommendations to better promote the availability and usage of RERs as well as the functionality of the EDDE. These include incorporating training on the EDDE and RERs into annual land use trainings for Community Boards; requiring RERs to be presented in-depth to bodies involved in the ULURP process; and improving the EDDE’s functionality to allow users to generate more customized data.

RERs should offer more narrative and meaning, not just supply required data

While the purpose of the RER legislation is to provide data so that people can come to more informed conclusions on a land use action, simply providing more data does not actually make it easier for the public to find information that can inform their understanding of a proposal. Indeed, this is a criticism of environmental impact statements, the long-standing report meant to provide public data so that stakeholders can make more informed decisions. Not only does raw data need to be provided, context for that data needs to be provided as well. This is especially true in a city as demographically complex as New York. Future focus should be on improving the analysis of this data as well as the overall narrative of RERs. This could be done in three main ways:

- Integrate various data points in order to enable more comprehensive analysis. In the absence of clear conclusions about a project’s potential effect on racial equity, readers are left to draw their own conclusions from the data the RER provides. The problem is that making connections between data in disparate sections of RERs is not necessarily intuitive. Requiring greater integration of project-specific and community-level data, such as placing affordability levels from the project-specific section side by side with the median incomes from the community profile, would make it easier for the public to gauge the impacts of a project on their community, as outlined earlier in the discussion section connecting race and affordability in the Sheridan Boulevard project. Potential forms this could take include a dedicated charts section or updated guidance on writing the narrative section.

- Add more context to the proposal’s likely effects. This could include a requirement to provide a “no action” analysis to RERs. There could also be more references to how a land use proposal would contribute to the city’s quantitative policy targets for either the neighborhood or city overall, including New York’s housing production targets, which are due to be published for the first time in 2026.18

- Add a historical narrative to RERs. This is especially important given the inclusion of Historic District designation as something that has the potential to trigger RERs. While RERs are focused on a neighborhood’s current and future racial equity, there is, of course, a historical component to it as well. That historical component should be expounded on so that it too can inform the public discussion, especially as it relates to other past government actions that impacted racial equity. Whether or not the physical preservation of things such as the former Boerum Hill Mohawk institutions—which have only historical, and not current, relevance—are useful in leading to racial equity is debatable. But this debate should be held in the public sphere and be expanded to more land use actions than just Historic District designations.

Where possible, RERs should also provide better or more granular data

The data RERs provide are generally thorough, reliable, and consistent across reports. However, the geographic units used to estimate and describe sociodemographic statistics are not always representative of the areas affected by the land use actions under review. If different, more granular information is available, it should be used. This could also allow the study area of an RER to better match the study area of an EIS/EAS. The city could also explore other ways to itself produce better underlying data or better access to existing underlying data. This has already started to be done with HPD’s new interface to the triennial Housing and Vacancy Survey it conducts.

Base displacement risk on observed data over time and implement periodic quality control review of RERs

As mentioned earlier, the displacement index developed for the EDDE is untested when it comes to its actual ability to predict displacement. Neighborhoods are given a “displacement risk” rating, and the predictive effect of this rating should be evaluated over time. If areas that were quantified as higher risk do not, on aggregate, experience more displacement than those quantified as lower risk, the index should be iterated with the goal of developing a more rigorous methodology with proven correlation to observed displacement. Especially in terms of studying racialized displacement, this should not be difficult. Spatially, race has 100% data in every decennial census and is well enumerated in other data sources.

Until this is done, the EDDE should also contain a disclaimer that it does not provide any objectively tested measure of displacement risk and should not be relied upon to actually predict future neighborhood displacement.

In addition to improving the EDDE methodology, a periodic quality control review of the EDDE interface—as well as both the RER regulations and a sampling of submitted RERs—should be done, and recommendations made to ensure that RERs not only meet the letter of the law, but are also highly informative and quality reports that reflect methodological rigor.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors of this report would like to thank Tracy Hadden Loh and Xavier de Souza Briggs for their assistance in developing, guiding, and refining this work; Sarah Treuhaft and Andre Perry for review; Michael Gaynor and Mary Elizabeth Campbell for editing; and Christine Garner for assistance with geographic information system mapping.

-

Footnotes

- Land use actions that go through full environmental review and are required to produce an EIS do generally quantify potential direct and indirect displacement for both residents and businesses. For specific methodology, see New York City’s Environmental Quality Review Technical Manual Chapter 5: Socioeconomic Conditions.

- Regional Plan Association, which employs the authors of this report, submitted testimony in favor of this rezoning to the City Planning Commission, which can be found here.

- It should be noted that the displacement risk designations of the affected areas have changed since the RER was conducted, with the Jamaica NTA now labeled with the “highest” displacement risk designation.

- Media mentions for this project were analyzed for the time period up to when the borough president’s office released their recommendation for the plan, and do not include mentions after June 30, 2025.

- The designation of the NTA encompassing the 2560 Boston Road application has recently changed to “high.”

- These are Goal 2 (“Build more housing in all neighborhoods across New York City and the region”); Goal 5 (“Expand and improve housing options and accommodations for people with disabilities”); and Goal 6 (“Improve conditions, services, and infrastructure in historically disinvested neighborhoods”). For the full index of which RERs addressed which goals of Where We Live NYC, see Table 1.

- Boston Road transcripts from CPC, City Council; Roxanne Delgado.

- It should be noted that one possible explanation for this discrepancy is that email testimony for the Boston Road development is available through the NYC City Council’s Legistar portal, whereas similar testimony is not available for the Sheridan Boulevard project.

- This practice may be curtailed by the City Charter Commission ballot proposals due to be voted on in November 2025.

- The seven census blocks that contain the extension are 67% white (2020 census), and the three census tracts that contain the extension have a median household income of $137,000, which is 72% higher than New York City as a whole (2019-2023 ACS).

- These are the Downtown Brooklyn-DUMBO-Boerum Hill NTA and the Cobble Hill-Carroll Gardens-Red Hook NTA.

- We were not able to transcribe the public hearing and run the script to search for terms; instead, we manually took notes on all commentators.

- We could not find any record of anyone self-identifying as a member of the Mohawk nation testifying or otherwise making any public statements on this action.

- In Regional Plan Association’s 2017 report on displacement, we found a correlation with observed residential displacement and both the number of very low- and low-income renters without significant rent protections and walkable areas with good access to jobs and transit.

- There is, however, the possibility of replicating the methodology of the EDDE for earlier data, and then testing it against past observed displacement. This is what Regional Plan Association did for Pushed Out, testing its proposed index against how well that same index would have predicted displacement from 2000 to 2015. For specific methodology, see the “Methodology” section of the report.

- Because of relatively small sample sizes, 5-year ACS estimates contain significant margins of error, especially in the case of the non-Hispanic Asian American population.

- See Appendix for the full analysis of the qualitative comparisons of the four RERs examined.

- This is required by the passage of New York City’s Introduction 1031A of 2023.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).