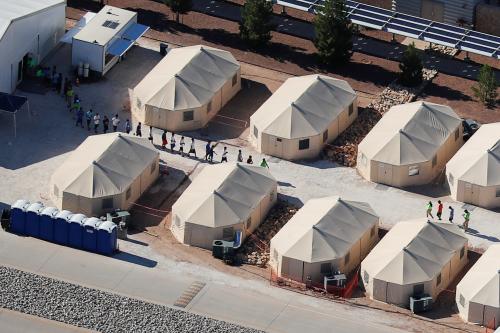

While President Trump has triggered political and moral havoc on this side of the Atlantic by separating migrant children from their families at the U.S.-Mexico border, Europe is also in the midst of consequential battles over migration. At stake is the European Union’s system of open borders between Schengen Area countries, the political survival of the continent’s long-tenured de facto leader, and the power balance between the pro-EU center and nationalist demagogues across the bloc, in addition to the wellbeing of thousands of people on the move.

Led by its confrontational far-right interior minister Matteo Salvini, Italy’s new populist government is refusing ships carrying rescued migrants access to its ports. Meanwhile, Angela Merkel’s 13-year chancellorship in Germany is threatened by a dispute with her Christian Democrats’ Bavarian sister party, which holds the interior ministry, over the handling of refugee arrivals. Discontent with Merkel on the German right could still lead to a divorce between the Union parties after seven decades, bringing down the government, ending Merkel’s career, and further splintering the German political system. Austria’s ambitious young chancellor, Sebastian Kurz, who will take over the European Council’s rotating presidency next week, is calling for a Rome-Berlin-Vienna “axis of the willing against illegal migration” and threatening to reimpose border controls with Italy on the busy Brenner Pass. Meeting with French President Emmanuel Macron last Tuesday, Merkel finally gave clearer answers to the EU initiatives Macron proposed in his Sorbonne speech last September. While the “Meseberg Declaration” includes ambitious proposals on reforms to the governance of the eurozone and EU institutions, migration policy was the topic of the hour.

All of this will come to a head on Thursday and Friday, when European leaders convene in Brussels to discuss migration and asylum policy. Political tensions are running so high that European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker convened an informal “mini-summit” of 16 of the bloc’s 28 countries over the weekend to prepare the groundwork. That meeting, at which Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte presented a 10-point plan, arguing that Schengen was at risk, concluded without a formal joint statement.

With the interests of arrival and destination countries so divergent, and the quarrels between their leaders so bitter, it is hard to imagine that the coming gathering will result in significant progress. For years, Europe’s leaders have unsuccessfully attempted to reform the Dublin rules, which assign responsibility for asylum seekers to the country they first enter. There is little reason to believe they will be able to do so now.

Yet progress is not out of the question. That’s because, despite Salvini’s appalling rhetoric (“We need a mass cleansing, street by street, piazza by piazza, neighborhood by neighborhood,” he said in an interview last year that received renewed attention after he announced a “census” of the country’s Roma community), Italy needs a common European solution more than any other government present at the summit—with the possible exception of Germany.

Salvini may have a kindred spirit in Hungary’s vitriolic, anti-migrant Prime Minister Viktor Orbán, whose parliament just passed a series of laws that allow the government to imprison individuals and nongovernmental organizations for assisting undocumented migrants, but geography matters. And Hungary and its Visegrád Group partners—the Czech Republic, Poland, and Slovakia—are largely responsible for the failure to reach agreement on a collective response within the bloc, rejecting EU proposals to implement resettlement quotas that would ease the burden on frontline countries including Italy. The four central and eastern European countries skipped the mini-summit, pushing back on what Orbán called a “pan-European frenzy.” Ultimately, if Italy wants a refugee burden-sharing scheme, and the perpetuation of Europe’s system of open borders, Merkel, not Orbán, is its ally.

On the table for this week’s summit is a proposal to send migrants rescued at sea to asylum processing centers outside of Europe for adjudication of their claims. At play are numerous legal and ethical issues. Any such plan would need to respect the principle of non-refoulement, the legal requirement not to send people back to places deemed to be unsafe, which the European Court of Human Rights concluded applies to processing that occurs outside of Europe’s borders. It would also need to ensure procedural rights, including the right to an interview and an appeal.

Then there are the practical issues, namely, where these “disembarkation platforms” would be placed, and what incentives the EU would need to provide to countries that agree to host them. Albania, which sits along the “Balkan route” for overland migration and is outside of the European Union though an official candidate for accession, has been raised as a potential host, as has Tunisia, but there is little evidence thus far that either country is willing. Even more fraught is the question of who would be authorized to take asylum decisions, and the criteria on which they would be based. Establishing a joint body would require member states to agree on applicable law and on a plan for accepting those whose claims are successful. That might lead right back to the current conundrum: a set of bitter battles over quotas.

All the while, people are at risk. More than 34,000 migrants and refugees have died attempting to find a new home in Europe since the early 1990s. According to survivor accounts, more than 200 people drowned off the coast of Libya in several unrelated incidents just last week. As the stalemate between European countries deepens, almost 350 refugees and migrants remain stranded on two boats in the Mediterranean. The geopolitics of this week’s meeting are salient, but its human consequences are every bit as significant.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Europe tussles over migration politics

June 26, 2018