This op-ed was originally published by Project Syndicate.

The nomination earlier this month of David Malpass, a senior U.S. Treasury Department official, for the post of World Bank president came as something of a relief. Malpass is, after all, the choice of U.S. President Donald Trump, who is known for backing extreme and unqualified job candidates. But that does not mean that Malpass is the ideal choice for the job.

In fact, while it could have been worse, Malpass’ nomination was a distinct disappointment. For one thing, his skepticism toward multilateral institutions runs deep. For another, he is a Trump loyalist who has often stressed the paramount importance of economic growth—especially U.S. growth. More fundamentally, Malpass is conservative, and the World Bank is not.

To be sure, the World Bank was once the standard-bearer of economic orthodoxy, reflected in the post-Cold War policy cocktail of privatization and deregulation known as the Washington Consensus. The institution codified a set of archconservative rules on trade, capital flows, and fiscal and monetary policies, with which it then compelled developing economies around the world to comply.

But, over the years, the Washington Consensus has come under fire, with some of the most cogent attacks coming from a former World Bank chief economist, the Nobel laureate Joseph E. Stiglitz. Among other things, Stiglitz pointed out that the Washington Consensus was not a consensus at all. Instead, it was “a set of policies formulated between 15th and 19th streets” in Washington, D.C., by the U.S. Treasury, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank.

By now, the World Bank, the IMF, and economists have moved away from the Washington Consensus. It is now widely recognized that devising effective economic policies demands sensitivity to the local culture and mindset, and that beyond reducing poverty, efforts must be made to curb inequality. After all, by stifling the voices of the poor—and giving the wealthy undue political influence—high inequality undermines democracy.

This is particularly important for the World Bank. Unlike the IMF, which is responsible for headline-grabbing responses to financial or economic crises, the Bank focuses on long-term solutions to longstanding problems, such as chronic poverty, malnourishment, and the retreat of water tables. That explains why four former World Bank chief economists were among the 13 economists from around the world who issued the 2016 Stockholm Statement, which summed up many of the views reflected in the shift away from the Washington Consensus.

Under Malpass, however, this progress could be undone, with the World Bank once again guided by the mantra of economic growth above all else. There is no reason to think that Malpass would uphold the World Bank’s commitment to fighting climate change, or that he would encourage consideration of local realities, inclusiveness, or equitable distributive outcomes in creating policies. It is far from clear that he would treat the world’s poor and poor countries with the appropriate respect or empathy.

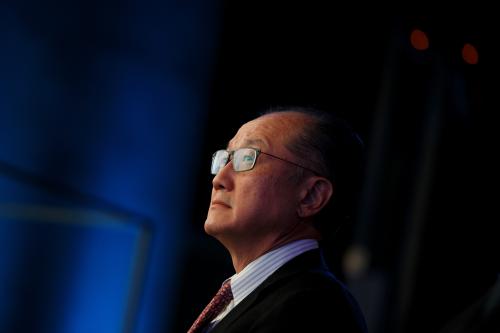

What the World Bank needs is someone loyal not to the U.S. president, but to certain ideals and ideas. And, while the World Bank has always had an American president, from Eugene Meyer to Jim Yong Kim, there is no official reason why this must be the case.

At the World Bank, the United States has the largest share of the vote—15.98 percent—followed by Japan (6.89 percent), China (4.45 percent), Germany (4.03 percent), and the United Kingdom and France (3.78 percent each). Given this, the U.S. need persuade only another nine or 10 countries to support its nominee.

This would be easy enough. But, historically, Western European countries have always supported the U.S. candidate, while the U.S. has always backed a European to head the IMF. These countries owe it to the world to rethink this arrangement, in order to ensure that the head of such an important global institution is chosen on the basis of merit alone.

To U.S. President Barack Obama’s credit, he appointed Kim, who beyond being a less-than-typical American (his father hailed from North Korea), had a track record of global engagement and a passion for development in some of the poorest regions of the world. Unfortunately, Kim left his post prematurely.

In this context, Europe, China, and India should be putting forward candidates as well, without regard for nationality. From Nigeria’s Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala to India’s Raghuram Rajan, there is no shortage of options.

If Malpass does end up getting the job, we can only hope that he will surprise us—and Trump—by standing up for global values and interests instead of American exceptionalism, and by prioritizing equity, poverty reduction, and sustainability over short-term growth. After all, Robert McNamara came from the killing fields of Vietnam to become one of the most progressive heads of the World Bank.

But that does not mean that Malpass should simply be handed the World Bank presidency. It is too important a position to be filled by default.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edEnding America’s World Bank monopoly

February 19, 2019