Editor’s note: This post is part of a Health360 special series that provides a look back at the impact of the Affordable Care Act since it was signed in March 2010. To view additional posts, click here.

For many of its fiercest critics the Affordable Care Act represents an unwarranted government takeover of the nation’s health care system. In fact the 2010 law assures that employer-provided private insurance will continue to play the central role in providing health coverage for working age Americans and their dependents. In many ways the law is designed to preserve employer-sponsored insurance by making it more comprehensive, less expensive, and more equitable than the system that existed when the law took effect. An inevitable result of the law is that it raises the cost of providing health insurance for some employers. One complaint of the law’s critics is that the added costs imposed on these employers will cause them to cut their payrolls or change employee schedules in order to minimize the law’s effect on their bottom line.

On the fifth anniversary of the law’s passage, what have we learned about the ACA’s impacts on employment?

The legal wrangles surrounding Obamacare mainly involve three aspects of the law: (1) the tax penalty imposed on Americans who are offered an affordable health plan but do not purchase one; (2) the requirement that states broaden eligibility requirements for the federal-state Medicaid program; and (3) the legality of insurance subsidies provided to Americans who obtain insurance through federally organized state-level exchanges. Indeed, the Medicaid eligibility expansions and the subsidies for coverage obtained through state-level insurance exchanges are key elements of the ACA that were intended to expand health coverage.

All the evidence on insurance coverage suggests these provisions have been successful in boosting the insured population and reducing the ranks of the uninsured. Some of the increase in coverage, however, is due to a change in mandated coverage under employer-sponsored plans. Since 2010 health plans that offer dependent benefits have been required to make coverage available until a child turns 26. The Department of Health and Human Services estimates that this provision enabled an additional 2.3 million adults age 25 and younger to enroll in an insurance plan.

The ACA established minimum standards on the health insurance provided under employer-sponsored plans. Some requirements increased the cost of providing health coverage for larger employers (those with 50 or more full-time equivalent workers). Employers that did not previously offer a plan are now required to offer one or to pay a sizeable financial penalty. Employers that offer parsimonious plans or plans that require heavy premium contributions from employees also face financial penalties.

These mandates and penalties have aroused opposition because of the fear that higher employer costs will curb hiring or induce some employers to create part-time rather than full-time jobs. While the fear is understandable, it is not clear whether the higher cost associated with improved insurance would be borne exclusively or even substantially by employers. Except in the case of minimum-wage workers there is considerable evidence that most employer costs associated with health insurance are passed along to workers in the form of lower money wages. Because workers place high value on the insurance benefits they receive, there is good reason to expect the additional cost of health benefits will be borne mainly by workers rather than employers.

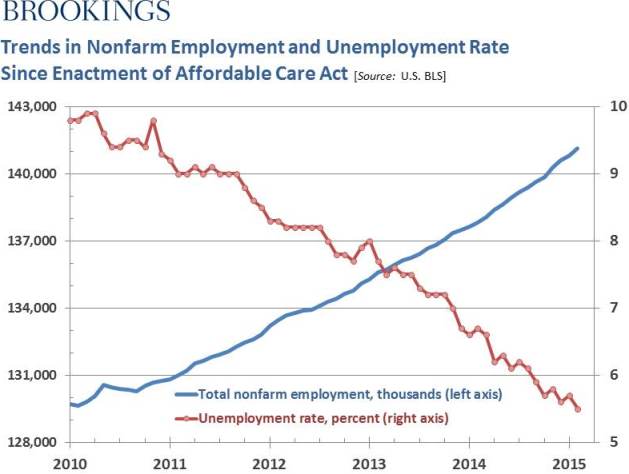

It is hard to evaluate the impact of the ACA on overall employment or on employee work schedules because the health law was passed in the middle of the worst downturn since the Great Depression. In the month the ACA was signed into law the unemployment rate was 9.9% and payroll employment was a bit less than 130 million. By February of this year the unemployment rate had fallen to 5.5% and employers had boosted their payrolls by 11.3 million (Figure 1). The pace of job growth has actually increased in the past few months as the Administration began to enforce the employer penalty provisions of the law. Of course, the drop in unemployment and rise in payroll jobs might have been even faster if the ACA had not passed. Nonetheless, it is not easy to make a convincing case that job gains have lagged since the President signed the health insurance law.

Figure 1: Trends in nonfarm employment and unemployment rate since enactment of the ACA

The effect of the law on employee work schedules is also unclear. Before the law went into effect some employees facing large medical bills may have worked on a full-time schedule in order to remain eligible for their employer’s health plan. Because the ACA made affordable insurance available to nonaged adults who do not hold full-time jobs, it may have encouraged some workers to accept part-time jobs and give up employer provided insurance. We might thus anticipate some increase in part-time work driven by employee preferences rather than by the changed incentives facing employers. As it happens, all of the job gains that have occurred since March 2010 have been in full-time employment. The number of workers who hold jobs that are usually part-time has actually declined modestly.

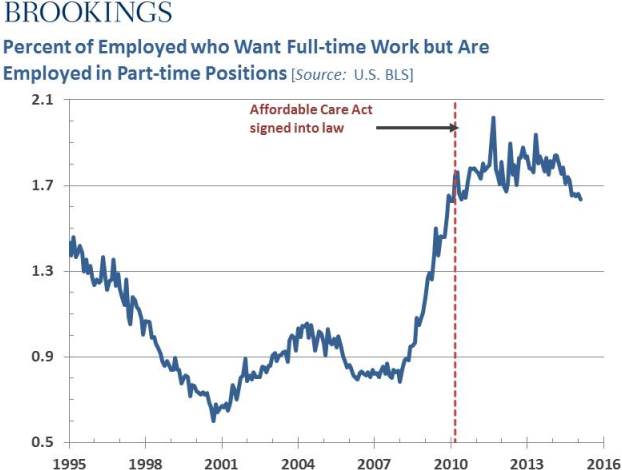

The question is, has the ACA increased part-time work among people who would prefer to hold full-time jobs? The severity of the Great Recession makes it hard to answer this question with much confidence. The percentage of job holders who have part-time jobs but who would prefer full-time work has dropped in recent months, even as the employer penalties have gone into effect (Figure 2). However, the percentage remains stubbornly higher than it was the last time the unemployment rate was 5.5%. If the entire gap is traceable to the impact of the ACA, the law has increased the number of workers who involuntarily hold part-time jobs by more than 1 million. My guess is that the number of workers who involuntarily hold part-time jobs has remained high because of the weakness of the economic recovery rather than the effect of the ACA. It is not easy to devise a statistical test that allows us to confirm this suspicion, however.

Figure 2: Percent of employed who want full-time work but are employed in part-time positions

Even if it were true that the ACA has induced employers to create more part-time jobs and fewer full-time jobs, it is not obvious whether this shift reduced workers’ well-being. To be sure, an increased number of workers hold part-time jobs who would prefer to work on a full-time schedule. Average hours per worker are therefore a bit lower. But if total work hours remain unchanged it also follows that more workers must hold jobs, reducing the number of involuntarily unemployed workers. It seems odd that critics of the ACA emphasize the potentially adverse impacts of the law on workers forced to accept part-time jobs but fail to notice that their logic suggests more workers in total must be employed.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Employment impacts of the Affordable Care Act

March 20, 2015