This blog is a summary of our new paper “Education system alignment for 21st century skills: Focus on assessment” and is the first blog in a series on the topic.

Education in the 21st century is not the same as education in the 20th century. We hear about the changing educational landscape time and again, but the real question is how is it different? In both centuries, education has been the main mechanism for individuals to gain core knowledge and concepts. However, now society demands that education systems equip students with the ability to go beyond learning core knowledge and concepts to using and applying them within the socio-cultural context of their societies. In other words, the 21st century has seen a major shift in learning goals—formal education sectors in countries all over the world want their young people to be able to think critically and creatively, solve complex problems, make evidence-based decisions, and work collaboratively. The major issue facing countries, then, is how to implement fully a 21st century skills agenda that focuses on teaching, learning, and assessment that is aligned with changing educational goals.

What is needed to incorporate a 21st century skills agenda into education systems?

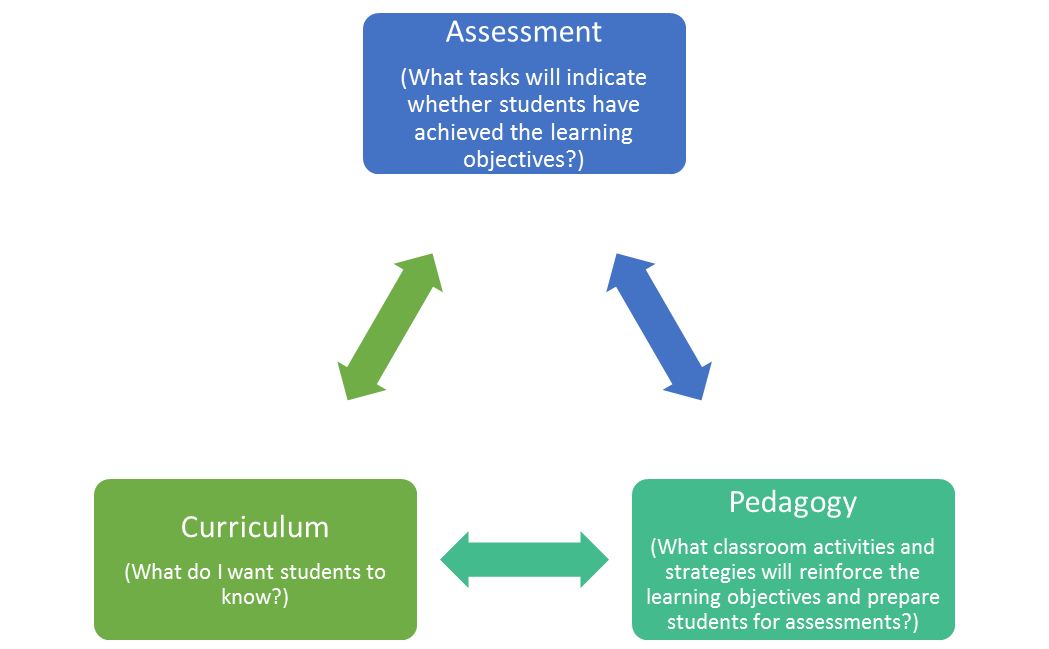

In short, what is needed is alignment, where the components of the system—curriculum, assessment, and pedagogy—are closely coupled to support student learning. Figure 1 shows what this looks like—that what you want the students to know (curricular learning objectives) is reflected by the kinds of tasks that indicate whether students have attained the learning objectives (assessment), which in turn, reflect the classroom activities and strategies (pedagogy) that reinforce the learning objectives and prepare students for assessments.

When the components are misaligned, learning can be compromised. For example, consider the following scenario: The learning objective is for students to learn to think critically and compare and analyze statements made by various authors, but the pedagogical strategies focus entirely on requests for summaries of the authors’ statements, and the assessment only captures information about which author made which statements. As a result, the task does not provide the opportunity for students to engage in the learning goal, and the assessment therefore cannot measure critical thinking or comparing and analyzing.

As evidenced by this example, when the components in the system are misaligned, changes in one component (e.g., curriculum reform) may yield few improvements in student learning if the other parts of the system, such as assessment and pedagogy, are not similarly adjusted. What you’re left with are outcomes that fall substantially short of what was intended.

Cartoon adapted from Henrik Kniberg

Cartoon adapted from Henrik Kniberg

Why is alignment so hard, and what can be done?

It boils down to the fact that alignment across curriculum, pedagogy, and assessment assumes that there is an understanding of the specific learning goals, but when it comes to 21st century skills, that deep level of understanding is not there yet. What does thinking critically mean? What does the developmental trajectory of critical thinking look like? What should grade level expectations be for critical thinking? Not having these answers, among many others, poses challenges to aligning the components of the education system and incorporating a 21st century skills agenda. In our paper published today, we highlight three key recommendations:

- First, we need to start from the basics and understand the nature of 21st century skills. What are the components, subcomponents, processes, and subprocesses involved in skills such as critical thinking, collaboration, and problem solving?

- Second, once there is understanding of the developmental nature of these skills, the focus needs to be on differentiating between levels of skills. One possible approach is to use learning progressions—pathways that describe how students typically achieve mastery of a particular learning domain or skills.

- Third, in order to capture and report on what students are able to do, assessments of 21st century skills should be authentic—that is, reflect what students will be asked to do in real-life situations beyond school.

Where to start?

Our paper provides examples of country reform efforts in the Philippines, Australia, and Kenya to address the shift in learning goals and to align their education systems. The primary route to shift learning goals has been through curriculum reform. However, the Optimizing Assessment for All initiative focuses on assessment as one strategy to align the components of the education system to the changing goals. Because the focus on a 21st century skills agenda is relatively new, it is unclear which approach is most effective.

A recent conversation with Mr. Ung Chinna, director of the Education Quality Assurance Department at the Ministry of Education, Youth, and Sport in Cambodia, provides some optimism: “We have never [in the past] thought about 21st century skills like collaboration or critical thinking. There are a lot of problems when we incorporate those kinds of skills … but we have to start somewhere. … New things are a challenge for us, for everybody, but I think everybody agrees with me that 21st century skills are very useful.” His message is clear—if learning goals are to be met, we do have to start somewhere. The challenges associated with incorporating 21st century skills into teaching, learning, and assessment are plenty, but these challenges also provide opportunities for us to learn.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Education systems need alignment for teaching and learning 21st century skills

January 30, 2019