There is now widespread, bipartisan agreement that mass incarceration is a huge problem in the United States. The rates and levels of imprisonment are destroying families and communities, and widening opportunity gaps—especially in terms of race.

But there is a growing dispute over how far imprisonment for drug offenses is to blame. Michelle Alexander, a legal scholar, published a powerful and influential critique of the U.S. criminal justice system in 2012, showing how the war on drugs has disproportionately and unfairly harmed African Americans.

Recent scholarship has challenged Alexander’s claim. John Pfaff, a Fordham law professor and crime statistics expert, argues that Alexander exaggerates the importance of drug crimes. Pfaff points out that the proportion of state prisoners whose primary crime was a drug offense “rises sharply from 1980 to 1990, when it peaks at 22 percent. But that’s only 22 percent: nearly four-fifths of all state prisoners in 1990 were not drug offenders.” By 2010 the number had dropped to 17 percent. “Reducing the admissions of drug offenders will not meaningfully reduce prison populations,” he concludes.

Other scholars, including Stephanos Bibas of the University of Pennsylvania, and some researchers at the Urban Institute, have made similar points in recent months: since only a minority of prisoners have been jailed for drug offenses, only modest gains against mass incarceration can be made here.

Stock versus flow

There is no disputing that incarceration for property and violent crimes is of huge importance to America’s prison population, but the standard analysis—including Alexander’s critics—fails to distinguish between the stock and flow of drug crime-related incarceration. In fact, there are two ways of looking at the prison population as it relates to drug crimes:

- How many people experience incarceration as a result of a drug-related crime over a certain time period?

- What proportion of the prison population at a particular moment in time was imprisoned for a drug-related crime?

The answers will differ because the length of sentences varies by the kind of crime committed. As of 2009, the median incarceration time at state facilities for drug offenses was 14 months, exactly half the time for violent crimes. Those convicted of murder served terms of roughly 10 times greater length.

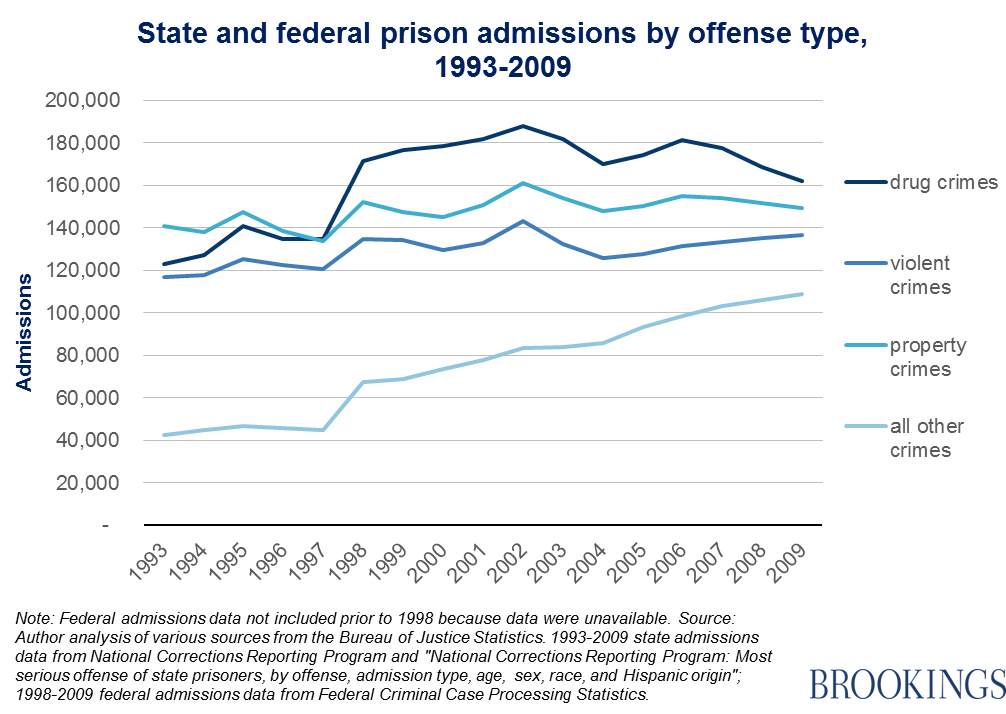

Drug crimes are the main driver of imprisonment

The picture is clear: Drug crimes have been the predominant reason for new admissions into state and federal prisons in recent decades. In every year from 1993 to 2009, more people were admitted for drug crimes than violent crimes. In the 2000s, the flow of incarceration for drug crimes exceeded admissions for property crimes each year. Nearly one-third of total prison admissions over this period were for drug crimes:

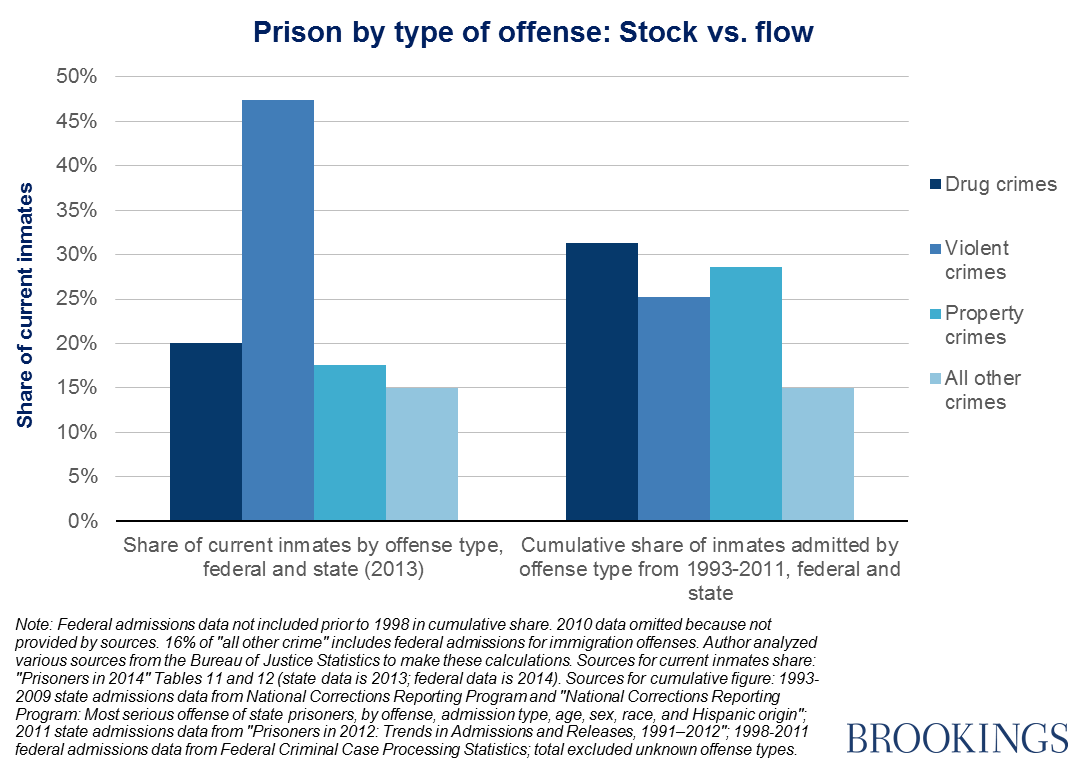

Snapshot pictures of prison populations tell a misleading story

Violent crimes account for nearly half the prison population at any given time; and drug crimes only one fifth. But drug crimes account for more of the total number of admissions in recent years—almost one third (31 percent), while violent crimes account for one quarter:

Being imprisoned and being in prison: The wider picture

So, as Michelle Alexander argued, drug prosecution is a big part of the mass incarceration story. To be clear, rolling back the war on drugs would not, as Pfaff and Urban Institute scholars maintain, totally solve the problem of mass incarceration, but it could help a great deal, by reducing exposure to prison. In other work, Pfaff provides grounds for believing that the aggressive behavior of local prosecutors in confronting all types of crime is an overlooked factor in the rise of mass incarceration.

More broadly, it is clear that the effect of the failed war on drugs has been devastating, especially for black Americans. As I’ve shown in a previous piece, blacks are 3 to 4 times more likely to be arrested for drug crimes, even though they are no more likely than whites to use or sell drugs. Worse still, blacks are roughly nine times more likely to be admitted into state prison for a drug offense.

During the period from 1993 to 2011, there were three million admissions into federal and state prisons for drug offenses. Over the same period, there were 30 million arrests for drug crimes, 24 million of which were for possession. Some of these were repeat offenders, of course. But these figures show how largely this problem looms over the lives of many Americans, and especially black Americans. A dangerous combination of approaches to policing, prosecution, sentencing, criminal justice, and incarceration is resulting in higher costs for taxpayers, less opportunity for affected individuals, and deep damage to hopes for racial equality.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Drug offenders in American prisons: The critical distinction between stock and flow

November 25, 2015