In the weeks since Justice Antonin Scalia died, much of the commentary around the vacancy has focused on Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell. In many ways, McConnell brought that outsized role upon himself. He quickly responded to Scalia’s death with a public pronouncement that the seat would not be filled until after the election. It caused an uproar over whether his plan was constitutional or beneath the institution.

But beyond all of that, McConnell was slapped with an allegation that is rarely launched at him: that he made a political mistake. But Mitch McConnell doesn’t make political mistakes.

So, to understand why he has carved his current path on the Supreme Court nomination, a sober discussion of Mitch McConnell’s incentives must be had. Aside from subjective judgments about what his choice should be, at the end of the day Mitch McConnell is a politician and a party leader. Other than his personal re-election (which is four years away), one goal rises above all others: maintaining the Republicans’ Senate majority and thus his position as leader.

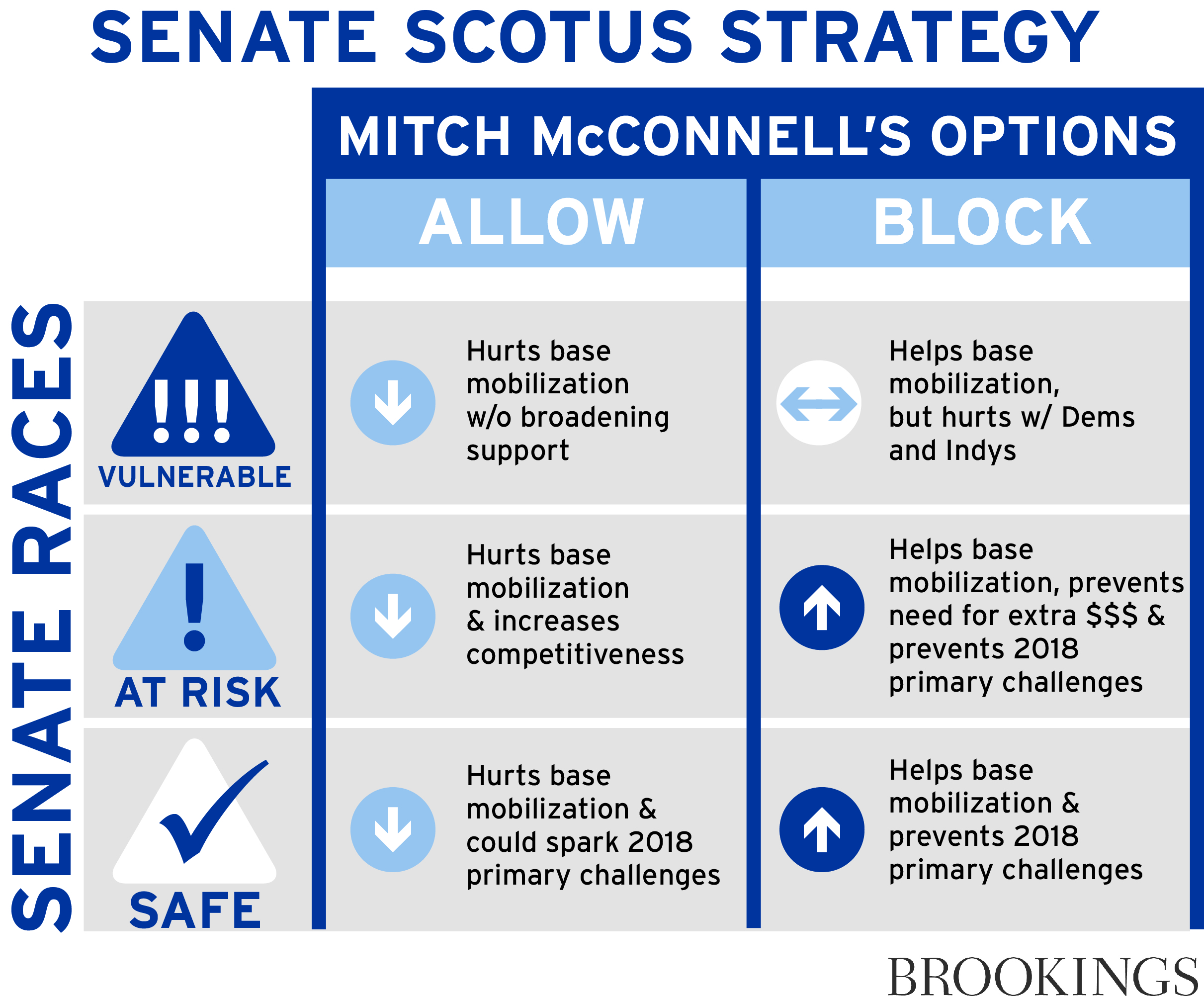

Thus, the choices over how to handle the Supreme Court vacancy proceed along two fronts for McConnell. The first involves the options he has. The second involves the consequences of each action for the Senate GOP.

McConnell’s choices

At first glance, it appeared that McConnell had three choices for how to respond to the current Supreme Court vacancy. He could block the nomination entirely, allow the nomination to proceed as ‘normal,’ or disingenuously “take a look” at the president’s nominee before actively working to defeat that person. It is from this set of choices that the incorrect perception of McConnell’s mistake emerged. Many of McConnell’s critics argued that the third option was his most strategically effective and that his passing on it was a bad choice.

The reality is that the SCOTUS song-and-dance option was never one McConnell entertained because it was a terrible choice. Holding meetings with and hearings on a nominee shifts the rhetoric around the issue away from principles and towards the specific qualifications of the individual involved, and Republicans have indicated they think the former is better for them than the latter. Considering a hypothetical nominee would be followed either by a public decision not to schedule a vote, or the eventual failure of the nominee (one who may be eminently qualified) at the hands of a Senate filibuster. McConnell would still be labeled an obstructionist by his opponents on the left, and the media would be unlikely to let McConnell off the hook for only paying lip service to the nomination.

At the same time, Republican leaders consistently fear the reaction of the party’s right flank and the activists on whom they rely for support. Any whisper or hint of a Republican leader working with the president is grounds for vocal opposition that can drive down enthusiasm among the base and have ripple effects throughout Republican politics. This dynamic helped bring down then-Speaker John Boehner and generated a Tea Party-backed challenger for McConnell himself in 2014.

That leaves McConnell with two options, each with benefits and costs. The first option is to proceed to consider a presidential nominee, allow a vote to happen, and let the chips fall where they may—including, possibly, seating a new justice. In this case, McConnell incurs the costs from the right flank described above, but avoids obstruction charges. What’s more, real consideration of a nominee—whether or not it produces an actual confirmation—might help the now-notorious group of vulnerable Republicans in seats up for re-election this fall outrun similar criticism—which is already coming in the form of ad buys from Democratic groups.

McConnell’s other alternative is outright obstruction. This approach satisfies the right wing, activist portions of the party, solidifying his position as a true conservative willing to fight the president no matter the price. It breathes fresh life and fresh fight into the conservative base and serves as a potentially unifying issue after a divisive Republican presidential primary season. On the other hand, the costs of this move include public criticism, particularly salient in an election year, of the leader for perpetuating a broken system in order to advance ideological purity on the Supreme Court.

McConnell, thus, faces a landscape with two diametrically opposed but viable options, each with pros and cons. Achieving his goal—maintaining the Senate majority—could hinge on his decision. So, understanding how those choices will affect Senate races is the key to deciphering the logic behind McConnell’s ultimate decision.

Scalia’s seat and vulnerable Republican senators

Much of the commentary surrounding the vacancy considers how it would affect “Vulnerable Senators” (typically Republican senators in Democratic or swing states). Certainly, this group matters—but so do two others: “Safe Senators” (those with effectively no risk of losing their seats) and “At-Risk Senators” (senators likely to win re-election, but who could face a more competitive environment under the right conditions).

McConnell’s decision to block or allow a nomination, are unlikely to prod voters to switch their vote in either direction. Indeed, recent polling from HuffPost/YouGov suggests that the Supreme Court fight is likely to be significantly outpaced by other issues at the ballot box this fall for most voters. If there are consequences, then, they are far more likely to come on the mobilization side of the equation. Mobilization encompasses a wide range of important factors in a race beyond voters’ direct choices, including voter turnout, likelihood of volunteering, fundraising, PAC support, and independent expenditure activity. McConnell’s decision can have positive or negative effects on mobilization for Republican senate candidates, alternatively increasing or decreasing his chances of keeping the Senate.

Through that lens, McConnell’s choice over whether to allow or block a nomination and its impact on mobilization within Senate races will be guided by three considerations:

- managing reasonable expectations about some losses among vulnerable GOP senators

- keeping the base happy to maintain turnout, funding and activism

- making sure that At-Risk Senators remain safe and do not require unnecessary additional funding and resources to win

McConnell’s SCOTUS strategies revealed

Option #1: Allowing the nomination to proceed

If McConnell allows the nomination to proceed—regardless of whether President Obama’s choice is confirmed—the outcome would mean an irate GOP base. Conservatives would feel betrayed if McConnell gave Obama’s nominee even a chance, and frankly, that anger makes sense. Replacing a deeply conservative justice (Scalia) with a liberal (Obama’s prospective nominee), would dramatically transform the already divided Court. Issues like abortion, the power of unions, the death penalty, states’ rights, immigration, affirmative action and a whole host of other hot button issues would likely be adjudicated with a notably more liberal skew. Another Obama appointee, especially one replacing Scalia, might also mean a revisiting and possible overhauling of Citizens United in a way that weakens the power of businesses and wealthy donors—an issue near and dear to McConnell’s own heart.

The result? Republican candidates and causes would face mobilization challenges party-wide. From the small corps of wealthy donors powering SuperPACs and other independent expenditures down to the army of grassroots volunteers who help get out the vote in states, the conservative cause would be weakened. If these people close their wallets, repurpose their time and energy, and ultimately fail to take up the mantle for their fellow conservatives—especially with the potential for a polarizing candidate at the top of the Republican ticket—the impact could be felt in every Senate race.

A Safe Senator, likely to win by 60 or 70 percent, can absorb mobilization challenges and still be re-elected. And, under this scenario, filing deadlines for congressional primaries will have passed, barring intra-party challengers in 2016. However, safe Republicans up for re-election in 2018—there are eight in total—could be concerned about being primaried. As Richard Lugar’s experience in Indiana in 2010 suggests, these concerns aren’t unfounded. Lugar entered the race as a “likely” winner, only to find himself eventually losing a primary to Richard Mourdock in part because of his support for the confirmation of both Elena Kagan and Sonia Sotomayor.

For At-Risk Senators, the decision to allow a nomination to proceed could pose a challenge. They would need to vote against a nominee to satisfy their base, thus limiting their appeal to Democrats and left-leaning independents. But allowing the nomination to proceed could lower base voters’ enthusiasm, meaning At-Risk Senators will have to work harder to mobilize the conservatives in their states. A lack of enthusiasm among the base likely won’t defeat one of these senators but could make an otherwise non-competitive race much more competitive. There’s certainly precedent for this as well, such as when Senator Pat Roberts’s (R-KS) 2014 race became substantially closer than expected because of mobilization challenges. A less energized base would mean the senator and the party would have to spend additional, unexpected funds in the state—funds put to better use in the states, congressional districts or in the presidential race. Traditional independent organizations like the Chamber of Commerce, Club for Growth, National Right to Life, NRA, and other groups may be less willing to commit funds to the race overall, putting additional burdens on the senators and the party.

Vulnerable Senators, finally, are in the most difficult position if McConnell allowed a nomination to proceed. Those coming from swing or Democratic states would have to face a serious choice over whether to support a Supreme Court nominee or not. Polling suggests many Americans support Obama’s filling of the seat. Vulnerable Senators then face a real choice between convincing independents (and even Democrats) to support them and staving off an angry Republican base. Supporting a nominee would produce the same mobilization challenges mentioned above, and base voters would become incensed if a Republican senator voted to confirm. It’s not clear, moreover, that any potential gains with independent voters would make up for lower enthusiasm among the base, as independent voters are notably less likely than partisans (of either party) to say that filling Scalia’s seat is “very important” to them. Ultimately, the decision to proceed with the nomination likely has little positive benefit for Vulnerable Senators, and for McConnell, it does little to reduce the chance of losing a few of those seats.

Option #2: Blocking the nomination entirely

McConnell’s decision to block the president’s Supreme Court nomination will not simply head off depressed mobilization among Republicans; it could energize the base, especially after a divisive presidential primary. Knowing that the Senate leadership is willing to play hardball in a conservative defense of Scalia’s seat could be a rallying call for conservatives across the country to get involved, appreciate the stakes of the election, and work hard to make sure that Democrats (as senators and/or a president) do not replace Scalia.

The option to block would be good news for Safe Senators, but likely have little impact on their races in 2016, simply increasing their margin of victory because of a mobilized base. However, blocking a nominee could also help prevent primary challenges among Safe Senators in 2018 by reducing the number of issues around which conservative activists could mobilize.

For At-Risk Senators, McConnell’s decision to block is potentially quite meaningful. Republican activists will be motivated and enthusiastic about the Senate taking the fight to the president, and that enthusiasm should spill over to Senate races. That enthusiasm, particularly in red states, will ensure GOP victories without worries about raising and spending additional funds. Yes, those senators will be accused of being obstructionists, but that message will likely ring true among Democrats (who were unlikely to support the Republican candidate) and independents (whose choices, as we saw above, are more likely to be influenced by other issues). Keeping these seats—think McCain (AZ), Murkowski (AK), Burr (NC), and the open seat in Indiana—from being truly competitive is essential for McConnell to maintain his majority and ensure a more effective distribution of campaign resources.

Vulnerable Senators, then, will face the greatest challenges from McConnell’s decision to block the nomination. The obstructionist label may be difficult for senators in blue and swing states to shed. Even though some are openly disagreeing with McConnell’s decision—an effort to distance themselves from the obstructionism—it is a difficult sales pitch at the end of the day. While McConnell’s choice may not change voters’ minds, it can become part of a broader narrative about a broken Washington that may ultimately become a serious issue in the campaign.

At the same time, McConnell likely expects that some of these senators will lose, even in the presence of an aggressive Supreme Court strategy. After all, he is on record as saying his goal for November is to “maintain but not grow” his majority. By blocking the nomination, he can make it easier to mobilize the base, which can assist even Vulnerable Senators, and perhaps, drive greater funding and support from SuperPACs and other independent groups that could assist in the defense of some of the vulnerable seats—an effort that has already begun with ads in vulnerable states.

Regardless of what McConnell chooses, Vulnerable Senators are going to face a tough time. If one operates along the assumption that the choice of strategy will not change many votes, but significantly affect mobilization, then the choice to block may be an effective means of limiting rather than eliminating losses.

McConnell’s SCOTUS choice is ultimately best for the GOP

Mitch McConnell didn’t make a mistake. The charges that he blundered his handling of Scalia’s death and the subsequent strategy to block any presidential nomination—are foolish. In fact, McConnell’s strategy, and the speed with which he worked through the possibilities to come to the “right” conclusion, was not a political misstep; instead, it is the mark of a political master. Mitch McConnell currently has his dream job—Senate majority leader—and will do whatever he can to maintain that position. In mathematical terms, that means losing no more than three Senate seats in the 2016 election.

Given the number of Republican senators up for re-election, the number of competitive seats, and presidential election year turnout, keeping the Senate majority was already a tall order for McConnell. So, his strategy around the Supreme Court vacancy is all that more important. It likely became obvious to McConnell that few people will switch from supporting a Democrat to a Republican or vice versa based on whether the Senate majority leader allows a vote on a judicial nomination.

Instead, McConnell recognized that Supreme Court nominations and decisions have significant effects on mobilization, and mobilization among voters, activists, and donors alike can play a significant role in elections. How the conservative grassroots, moneyed interests, and mega-donors respond to his strategy will have significant effects on Senate races, House races, and the presidential race this year, and it can even have ripple effects on races in the 2018 cycle. With an opportunity to maintain or even enhance conservative enthusiasm—particularly in a year in which the Republican Party appears to be on a confusing soul-searching mission—McConnell jumped at it.

His decision to institute an absolute prohibition of President Obama’s nomination of a Supreme Court justice will keep safe seats safe and prevent primaries in 2018; it will ensure that At-Risk Senators remain safe and without the need to spend additional resources. It will also provide McConnell a chance to stem some of the almost certain losses among Vulnerable Senators.

Allowing the president’s nomination to proceed might have looked nice for the cameras and may have produced a few stories about “McConnell the Statesman,” but at the end of the day it would have been seen as a devastating blow to the conservative cause and one that risked a multi-decade long upheaval in conservative jurisprudence. Individual voters may not see the Supreme Court vacancy as a life-or-death issue, but conservative interests do. The stakes over this nomination could not be higher. And frankly, if Mitch McConnell made a mistake in choosing the block the nomination, it’s the kind of mistake that conservative activists will applaud any day of the week.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Don’t judge McConnell on Scalia’s SCOTUS replacement

March 3, 2016