Federal spending on children edged down last year. As a result of the phase-out of stimulus programs as well as budget cuts imposed by the sequester, federal spending on children’s programs is expected to drop still further this year and next. Meanwhile, outlays on federal programs for the elderly continue to rise. Most of this spending consists of transfer payments under Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security. Virtually all that spending is protected against cuts connected to the sequester.

According to recent estimates published by the Urban Institute, the average American older than 65 now receives $6.66 in federal outlays for every $1.00 received by a child under age 19. Moreover, an overwhelming share of the spending on the aged is determined by benefit formulas that boost spending per person in line with increases in the cost of living or medical prices. Because medical costs have risen without interruption in recent decades and the share of the population past age 65 is increasing steadily, child advocates fear that kids’ programs will become orphans in a storm. Government spending on children will inevitably be squeezed as more public resources are diverted to fund programs for the elderly.

This fear is not without foundation. Based on the historical record, however, it appears wildly overblown. Core programs for children – providing public schooling and health insurance – have proven to be surprisingly resilient. Despite budget pressures to fund programs for the aged and for national defense and to pay interest on the national debt, per capita government spending on public schools and child health insurance programs has continued to climb. Big public programs for the aged may appear to operate on automatic pilot and hence to be immune to budget cuts. But presidents, governors, and legislators have also displayed an enduring regard for programs that educate and protect the health of children.

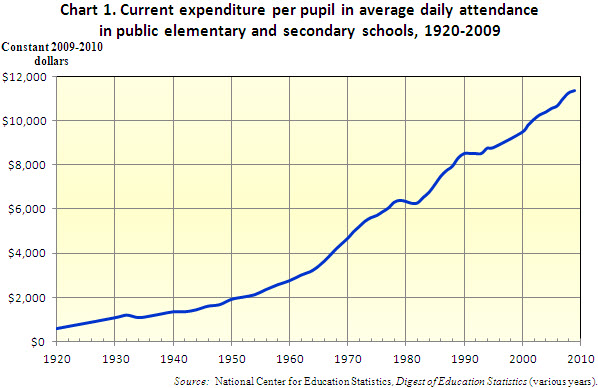

For example, per pupil spending on K-12 education has increased with virtually no interruption over the past 120 years. In the three decades between 1980 and 2009 real spending per pupil increased 2.3% a year (see Chart 1). True, per pupil spending on public schools climbed more slowly in the most recent decade than it did in the previous two. It only increased 2.1% a year between 2000 and 2009. Still, this rate of increase is considerably faster than the growth in per capita personal income during the same period. Notwithstanding the impact on government budgets of two recessions and two wars, per pupil spending on K-12 education continued to rise. The end of federal stimulus payments to state and local governments combined with state and local revenue problems have undoubtedly slowed educational spending growth since 2009. Nonetheless, it is hard to see evidence in the historical record that legislators will savagely cut outlays on public schools.

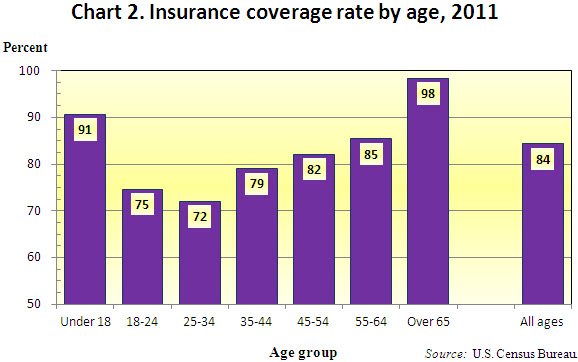

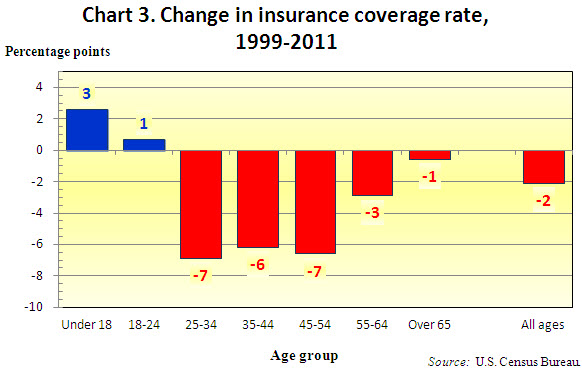

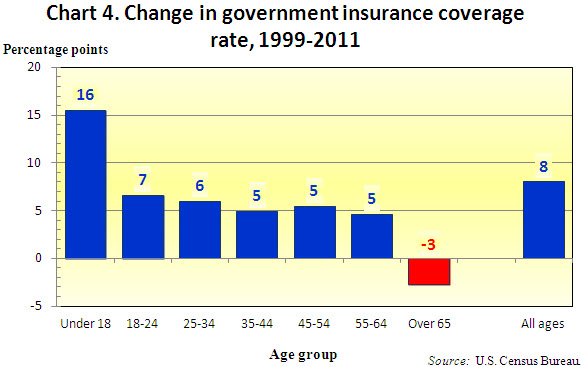

Government spending on child health insurance has also climbed steeply in recent years. The Census Bureau estimates that almost 4 in 10 children under 18 now obtain health coverage under a public insurance program. This represents a major increase in public coverage compared with the situation in the late 1990s. Rising rates of public health coverage have more than offset losses in child health insurance obtained under private insurance. In fact, since 1999 children under 18 and young adults between 18 and 24 are the only age groups in the population that have seen an increase in health coverage. All of the improvement has been due to expansions in government coverage. Meanwhile, Americans older than 25 have seen health coverage rates fall (see Charts 2 through 4).

Much of the concern over the future prospects of children’s programs arises from an understandable confusion over the source of funding for these programs. Since establishing the Social Security program in the great depression, the federal government has assumed a major role in assuring Americans’ old-age income security. Because personal savings and private pensions proved inadequate to assure safe retirement incomes in the 1930s, the national government established a contributory pension system that provided predictable, but modest, public pensions. The federal government has thus assumed the leading role in collecting contributions and disbursing benefits for old-age income security.

It has not assumed a similar role in assuring public benefits for children. The primary source of income support for children is parental earnings. State and local governments continue to play the leading role in education and public health insurance, though federal aid to states and localities is increasingly important in funding state and local commitments. Whereas the federal government spends $6.66 on each aged American for every $1.00 it spends on a child, state and local governments spend $8.88 on each child under 19 for every $1.00 they spend on a person older than 65. Since the federal government spends considerably more than states, total per capita public spending on the aged is higher that per capita spending on the young.

The crucial point, however, is that state and local governments are the primary source of funds for programs that provide education and other benefits to children. It is conceivable that budget pressures arising from increased health costs and an aging population will eventually cause public spending on youngsters to fall. The historical record provides little evidence to support this view, however. Long-term spending trends, both at the federal and local levels, suggest that core programs for children receive roughly the same budget protection as programs for the aged.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edDo Budget Commitments to the Old Shortchange the Young?

March 26, 2013