For a long time, economists believed that negative interest rates – charging savers to keep money in the bank instead of paying them interest – were close to impossible. If confronted with negative rates, people and institutions would hoard currency, economists reasoned. After all, earning zero interest on $500 in currency is better than paying a fee to keep $500 in the bank. Recently, however, central banks in Denmark, Sweden, Switzerland, the euro zone and Japan cut their rates below zero, testing those long-standing beliefs.

In 2009, the Swedish central bank, the Riksbank, introduced a negative interest rate on the reserves that commercial banks deposit at the central bank. Denmark’s central bank followed in 2012. A couple of years later, the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank moved to negative rates and the Bank of Japan joined them early this year. As a result, a quarter of the world’s economy is now experiencing negative interest rates as central banks seek to spur economic growth.

No evidence of cash hoarding so far

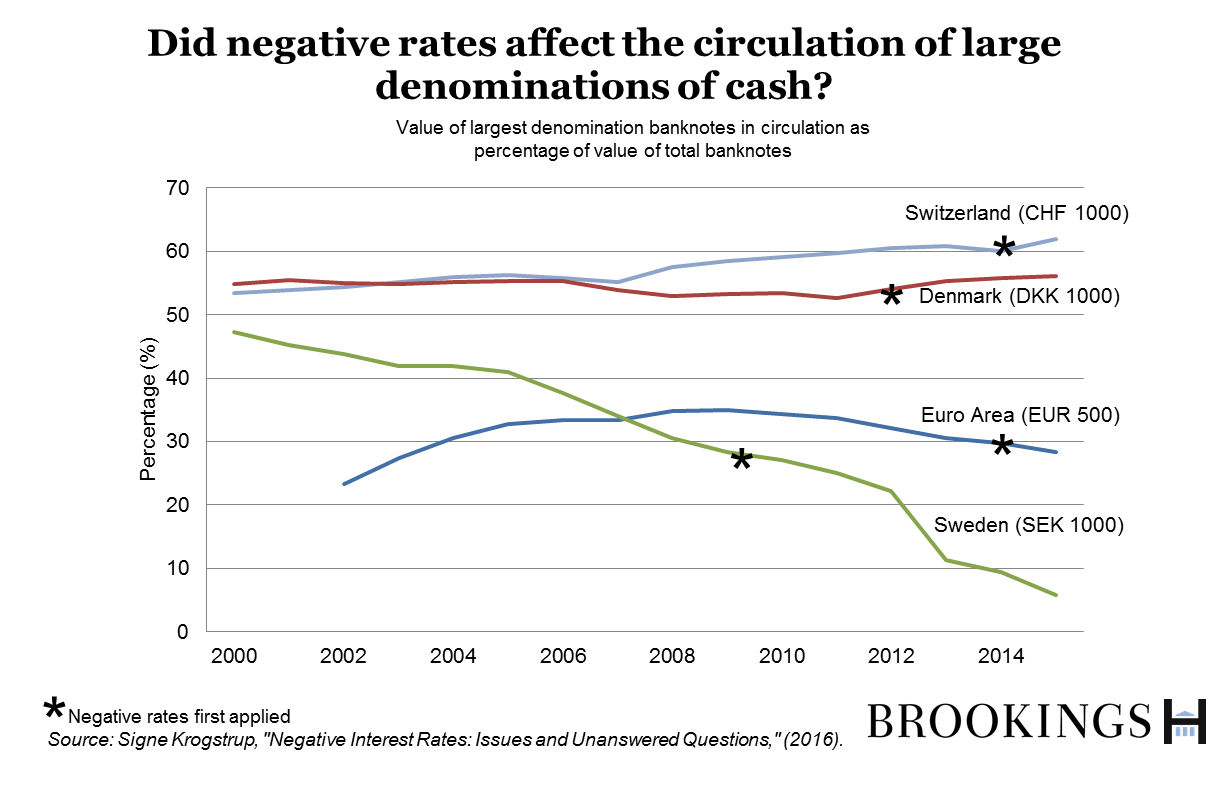

According to the available evidence, it doesn’t appear that cash hoarding is a problem right now in the economies with negative interest rates. One way to find out is to investigate whether people are holding onto large bills; if you wanted to hoard cash to avoid negative rates, it would be easier to hold onto the €500 note or the SF1000 note, not lots of €10 notes. In Sweden, however, the ratio of the value of 1,000 krona banknotes to all krona banknotes has been decreasing over the last 15 years (and has NOT turned up since rates went negative). In the euro area, the ratio of €500 banknotes to all euro banknotes began to fall a few years before negative rates were introduced in 2014, and this trend has not reversed. In Denmark, the ratio of the value of 1,000 krone banknotes to all krone banknotes has not changed significantly since 2012. There has been a noticeable increase in the share of 1,000 Swiss franc banknotes, but that trend preceded the arrival of negative interest rates. At a recent Hutchins Center at Brookings event, Jean-Pierre Danthine, former vice president of the Swiss National Bank, attributed this increase to angst about the banking system: “We have daily data so I can tell you it started right after Lehman Brothers.” As for Japan, it is too early to draw firm conclusions since the negative rates were introduced there early this year.

Another gauge of cash hoarding is the total value of paper currency holdings measured against the size of the economy over time. That metric differs significantly by country. It has declined in Sweden as people have favored electronic forms of payment over cash, but it has been stable in Denmark and risen slightly in Switzerland. The euro zone is an exception. Paper currency in circulation as a share of the economy has increased substantially, but this increase began well before negative rates.

The most obvious reason that households haven’t begun to hoard cash is that, in most countries, negative rates haven’t affected most ordinary customers—just the banks themselves. That’s in part because of the way central banks have structured negative rates and in part because of business decisions that banks have made to shield their retail customers. Another reason is that rates are only slightly negative – the most negative rate is the Swiss National Bank’s minus 0.75 percent on bank reserves. That may not be enough to justify the costs involved in storing large amounts of cash – buying safes, arranging insurance and so on.

Cash hoarding might be more common if negative rates persist

Economists agree that the longer negative rates are maintained (or the longer people believe they will be maintained), and the more negative the rates go, the more likely banks are to charge small depositors a negative rate and the more likely banks and their customers are to switch to holding cash. A tiny Swiss bank, Alternative Bank Schweiz, recently announced that it will start charging retail depositors a negative rate. And, of course, banks themselves could accumulate large amounts of currency to avoid the negative rates on their reserves at the central bank. There have been reports that Germany’s Commerzbank and Munich Re are considering storing larger amounts of cash in vaults. If more banks follow suit and customers begin to feel the impact of negative rates, the evidence may tell a different story.

For more on negative rates, see the Hutchins Center conference “Negative Interest Rates: Lessons learned…so far.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Did negative rates in Europe trigger massive cash hoarding?

June 17, 2016