On February 26, Iranians will begin the process of electing their tenth parliament. While much discussion has focused on implications for Iran’s foreign policy, the electoral process itself remains a mystery to many. Here are the basics of the Iranian parliamentary election process.

What is the Majlis, and what powers and responsibilities does it have?

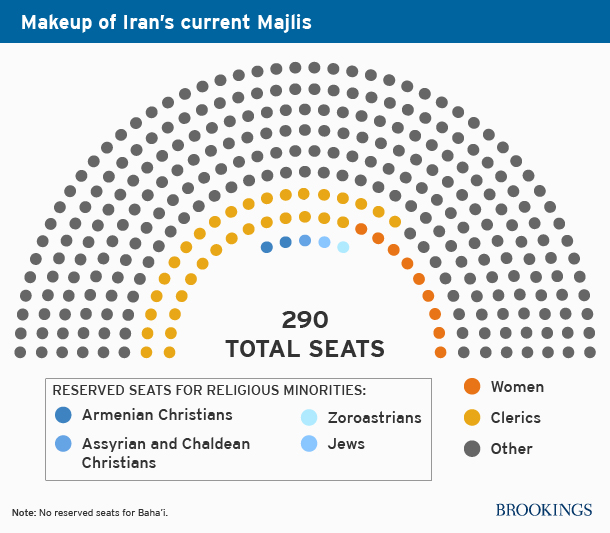

Iran’s Majlis—officially the Islamic Consultative Assembly (Majlis-e shoura-ye eslami), and in Western terms a popularly elected parliament—was established in the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution. While the Majlis is institutionally separate from the Guardians’ Council, an appointed body of 12 Islamic jurists, the Council plays a large role in the parliament’s elections and its legislative role. The 290 members of the Majlis represent Iran’s 207 electoral districts. Thirty seats are devoted to representatives from Tehran, the largest district. The second largest has only six seats.

The main responsibilities of the Majlis are legislation and oversight.

After the Majlis debates and passes a law, the Guardians’ Council must confirm that the law conforms to the Constitution and Islam. The veto power of the Guardians’ Council over legislation has meant that substantive political and economic reform—even if supported by the Majlis—has often been obstructed. (In fact, because approximately half of the bills passed by the parliament were later rejected by the Guardians’ Council, Iran in 1989 established a third legislative body, the Expediency Council, which is empowered to mediate between them and overrule both.) If approved by the Guardians’ Council, the piece of legislation must be signed by the president to become law. Among other things, the Majlis reviews and approves the annual budget, may approve and impeach heads of ministries, issues formal questions to the government, and approves international treaties.

Any public complaints against government organizations are handled by the Majlis. The body’s oversight authority is curbed, however, by the fact that the Supreme Leader’s consent is required if the Majlis wishes to look into an institution associated with his leadership.

Individuals and outside institutions are not supposed to influence Majlis decisionmaking. In 2000, however, Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei ordered that a bill concerning press law reform not be debated. The Supreme National Security Council has also been known to pressure parliament to pass certain resolutions. And members of parliament have complained episodically that the government does not implement or adhere to even those laws that are passed.

How is the Majlis elected?

Qualifying and campaigning

Members are elected every four years by direct popular vote. Although they are subject to considerable restrictions, parliamentary elections have been held regularly since 1980. To qualify to run for a seat, candidates endure numerous rounds of vetting. The Interior Ministry oversees initial vetting, but the Guardians’ Council ultimately calls the shots on who is qualified to run. According to Article 28 of the Elections Act of Islamic Consultative Assembly, candidates must satisfy the following criteria at the time of registration:

- Belief in and practical obligation to Islam and the holy system of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- Citizenship in the Islamic Republic of Iran.

- Expressed loyalty to the Constitution and progressive principle of the Absolute Guardianship of the Jurisprudent.

- A document proving possession of at least an Associate’s degree or equivalent.

- Not having a bad reputation in the electoral district.

- Physical health such that they at least enjoy the blessings of vision, hearing, and speaking.

- At least 30 years of age and at most 75.

(Religious minority candidates are not required to satisfy the first criterion.) Even if a candidate meets each requirement, the Guardians’ Council has been known to find excuses to disqualify parliamentary hopefuls. Incumbents may be disqualified.

The manipulation of the Iranian electoral system has garnered significant international criticism.

The manipulation of the Iranian electoral system has garnered significant international criticism. Freedom House stated that although “there were no claims of systematic fraud” in the 2012 elections, “several sitting lawmakers accused the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps of rigging activities.” According to Human Rights Watch (HRW), the Guardians’ Council has used information from undisclosed sources to disqualify candidates in recent years. HRW’s Sarah Leah Whitson stated that there are “serious structural problems that undermine free and fair elections” and that “certain officials arbitrarily act beyond their legal powers to leave virtually no alternative candidates for people to vote for.”

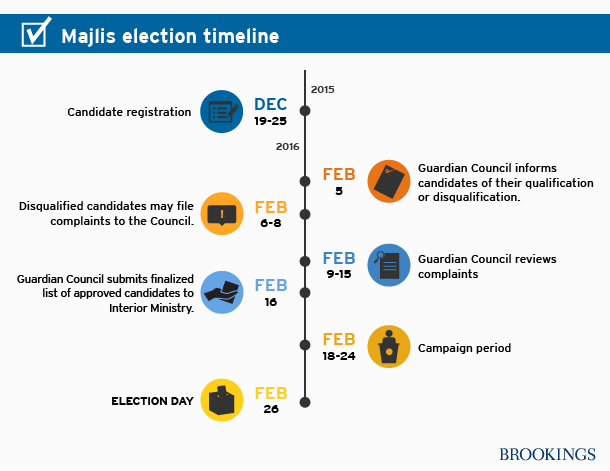

Approved candidates can officially campaign for just seven days. Campaigning will begin on February 18.

Election day(s)

On February 26, Iran’s tenth Majlis will be elected…maybe. A candidate is declared the winner if he or she garners the majority of votes in a district and 25 percent or more of the votes cast there. If no candidate reaches these standards, a second round of voting takes place in which the two top candidates in that district compete. The Guardians’ Council then has to approve the election results.

Who gets a seat?

Although the composition and authority of the Majlis is restricted by the Guardians’ Council, members of parliament harbor diverse and often opposing political views, real debate is frequent, and criticism of the government is permitted. The Majlis sessions themselves and the minutes are made public.

A degree of representation is guaranteed to religious minorities: two seats to Armenian Christians, one to Assyrian and Chaldean Christians, one to Jews and one to Zoroastrians. Iran’s largest religious minority, Baha’i, is not officially recognized and is not granted a seat (and their political and social rights are severely circumscribed by the regime).

Currently, there are nine women in the 290-member body (3 percent). Although the final list of approved candidates has not yet been announced, in late January only one major female reformist had been approved by the Guardians’ Council. Many believe that the disqualification of women candidates is linked to the fact that many women who registered as candidates have feminist and human rights activist backgrounds.

In 2006, the parliament passed a law requiring all candidates to hold a master’s degree. This scrutiny on educational attainments parallels a steady decline in the number of MPs who are clerics, from a high of 131 in the first parliament to 33 in the current body.

The strength of the Majlis has been hindered by the absence of political parties and the low incumbency return rate—about 30 percent in the last nine elections. As the University of Toronto-affiliated website Majlis Monitor explains, the political groupings that mobilize to contest Iranian elections are more accurately described as “political currents” rather than political parties in the Western sense. Whereas parties usually have set organizational structures and platforms that remain more-or-less consistent, “political currents,” according to Majlis Monitor, “usually emerge as alliances of convenience to pursue common political-ideological agendas, economic interests, and constituencies.”

[T]he political groupings that mobilize to contest Iranian elections are more accurately described as “political currents” rather than political parties in the Western sense.

What now?

On January 17, the Guardians’ Council announced its initial approved list of candidates, suggesting that only about 40 percent of the registered candidates were approved. According to Human Rights Watch and Iranian reformist politicians, many disqualified candidates were barred from running due to their political beliefs. The disqualified candidates are given a chance to file complaints, and the final list is due to be announced the week before elections are held. The latest reports indicate that an additional 1,500 candidates were approved to run after the Guardians’ Council reversed their initial disqualifications, bringing the total number of candidates to approximately 6,200. If true, that would make the 2016 parliamentary elections the largest field in Iran’s post-revolutionary history, although it remains to be seen how politically diverse this pool may be.

Click here for more information on Iran’s Assembly of Experts election, taking place the same day.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Demystifying Iran’s parliamentary election process

February 9, 2016