This is Part 2 of a series which will take an in depth look at election deniers in the 2022 midterms in an effort to assess their likelihood of success, their plans if elected, and their impact on election administration and democracy.

As has been reported in these pages and in other publications around the country, there are many candidates on the November ballot who think the 2020 election was fraudulent (so-called, “election deniers”). A substantial portion of them seem poised to win. So, what will their victories mean for elections in 2024 and beyond? To better understand this question, we have looked at as many campaign proposals as we could find, beginning with candidates for secretary of state, governor and attorney general because these offices hold the most power and responsibility over elections. This piece will attempt to describe the agenda(s) of those who are running as election deniers with respect to how elections are run in the United States and to assess the impact on democratic elections should they succeed.

The Covid Election

One of the central roots of the election denier movement lies in the COVID-19 pandemic. The explosion of the pandemic occurred in 2020—an election year before vaccines were available. In the first eight-months of the year (when most decisions about the fall elections were being made) over 138,000 Americans had died of COVID. In the fall of 2020, as those decisions were being implemented, cases and deaths began a precipitous rise. On the eve of Election Day 2020 alone there were 447 deaths reported, pushing the total since the first death in late February to 231,353.[1] On Election Day the seven-day average for hospitalizations was 45,690 and climbing. After a summer where the pandemic seemed to be slowing, colder weather in the fall brought a spike in the pandemic, one that would crest in the winter of 2020 and into 2021 with enormous numbers of hospitalizations and deaths.

In the face of panic and uncertainty during the first year of the pandemic, election officials and voters in every state had to decide how to handle the upcoming election.

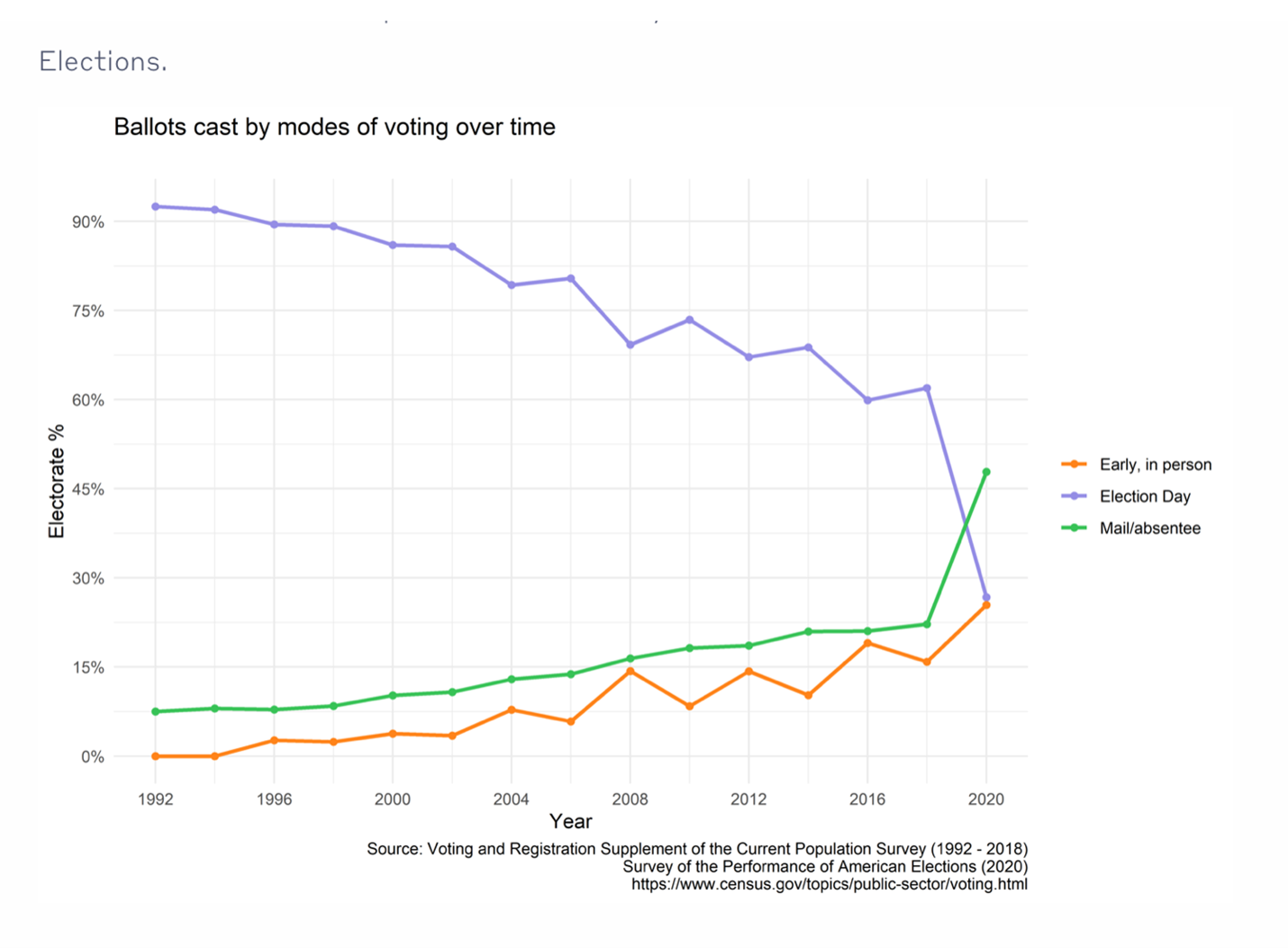

The answer they turned to initiated one of the most dramatic changes the nation has ever seen in terms of how people voted. States engaged in an unprecedented degree of innovation around absentee ballots and early voting, making maximum use of existing procedures or adopting new ones. Millions of Americans, reluctant to go into public places for fear of infection, adjusted fairly easily to casting absentee votes and/or voting early. On Election Day, more than half of all Americans voted absentee or early. This chart from MIT shows how Americans have cast their ballots from 1991 to 2020. Prior to 2020, there was a slow but discernable tendency to vote early or by absentee ballot. But COVID supercharged those trends so that by Election Day 2020 less than 30% of voters cast their ballot in person on Election Day.

The changes in voting in the 2020 election had two contradictory effects. On the one hand, voters loved the convenience and the fact that in a time when any foray into the public was dangerous to their health, they could vote from home or drop off a ballot from their car. Turnout in the 2020 election—in the midst of a pandemic—exceeded all expectations. On the other hand, the changes convinced President Trump that the availability of mail-in and absentee ballots would lead to enormous fraud and provided part of the basis on which Trump would declare the election fraudulent. This was new in American elections. Never before had these types of voting been an issue, but well before Election Day, and against the advice of some of his campaign aides, Trump started a campaign against mail-in voting in all its forms, tweeting: “Republicans should fight very hard when it comes to statewide mail-in voting. Democrats are clamoring for it …Tremendous potential for voter fraud, and for whatever reason, doesn’t work out well for Republicans.” [2]

It should be noted that despite the false claims that mail-in voting hurts Republicans and that voter fraud would damage the GOP, 213 Republicans won U.S. House seats, 20 of the 33 Senate seats up on Election Day, and eight of the 11 governors’ races.

Having politicized how people voted, it was no surprise when, on Election Day, Republicans tended to turn out to vote in-person and Democrats tended to vote early or absentee. This is what Trump and his campaign anticipated—creating what has come to be known as the “red mirage.” Since a large number of Republicans turned out in-person, and those votes are often counted first, the earliest returns in a number of states tended to show Trump in the lead. And yet, as the night and following days demonstrated, once the absentee ballots arrived and were counted, the tally changed as well. On November 7, 2020, most national news outlets called the election for Biden.

The Election Deniers’ platform

The election denier movement includes three broad election administration agendas:

- Changing how votes are cast,

- Changing how votes are counted,

- Changing control of election results.

As a threshold matter, it should be noted that many election deniers also support policies which are efforts to suppress the vote, such as creating requirements that voters be removed from the voting lists and demanding stringent voter identification. In Arizona, a House bill would require routine investigation of the citizenship status of suspected non-citizens. Others call for steps that would remove voters from the rolls.

Many of these voter suppression efforts have been described and fought about for many years. In this essay we will focus our survey on the more recent plans of election deniers when it comes to voting, counting votes and certifying winners.

Changing how votes are cast

Given the enormous decline in in-person Election Day voting during the pandemic, election deniers have turned their attention to abolishing or limiting absentee and early voting. No widespread fraud has been proven in any state that used either vote-by-mail, no-excuse absentee voting, or early voting. But a variety of off-the-wall theories about voting by mail have gained traction in the election-denial movement—suggesting that the actual motivation for these theories is to inflame supporter suspicion, to denigrate and disadvantage election opponents and their voters, and to advantage preferred candidates irrespective of actual vote outcomes.

In the days after the election, Trump, who voted absentee himself, spread unsubstantiated theories about the election. He alleged that there were more absentee ballots cast in Pennsylvania than had been requested and that a “suitcase” in Georgia had been wheeled into a Georgia counting facility stuffed with fraudulent ballots. In Arizona, Republicans would later examine ballots for bamboo fibers—based on speculation that 40,000 ballots had been flown into Maricopa County (Phoenix—an area that went for Biden) from China.

Thus, almost every election denier wants to do something about voting by mail. Currently, eight states (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Vermont, and Washington) allow the conduct of their elections to be entirely by mail.[3] Oregon was the first state to move to all mail voting in 2000. They have thus used this system for decades and the amount of fraud discovered over the years is trivial and would not have changed any election results. Furthermore, voters in these states are accustomed to, and like, their mail-in ballot systems, and they are mostly states which have few election deniers likely to win elections.

There are 13 secretary of state candidates running on the Republican ticket this fall. We reviewed the platforms of each candidate focusing on their website and on their campaign Facebook pages to try and ascertain their agenda if elected. Eleven candidates want to limit absentee and/or early voting.[4] The two exceptions are candidates in deep blue states, Vermont and Connecticut. In deep blue Vermont, the election-denier candidate merely calls for “reviewing” the state’s vote-by-mail system for fraud. In Connecticut, the election-denier candidate wants to promote curbside voting—where an election official can bring a ballot to someone’s car if they are unable or afraid to enter the polling place.

There are a variety of agendas among the candidates who would roll back vote-by-mail and early voting. A favorite target of these candidates is “no-excuse” absentee balloting. Prior to the pandemic, many states required the voter to provide an excuse in order to receive an absentee ballot. In some states, the excuse had to be proof of travel out of state. In others, an absentee ballot also had to be witnessed and notarized. Federal law requires that states make exceptions for military on deployment but, prior to 2020, outside that military exception, absentee balloting had not been a universally available process. Then came the pandemic and in 2020 nearly all states offered no-excuse absentee balloting.[5]

Today’s election deniers have focused on proposals they claim will make the absentee ballot process more secure in spite of a dearth of any proven fraud in 2020. Many want to ban “no-excuse” absentee balloting and restrict early voting, a reversal of the trend that happened in the summer of 2020. The movement would also like to ban mass mailings of absentee ballots—which are, by definition, “no-excuse” ballots.

There are calls for abolishing “drop-boxes” for absentee ballots, limiting the number of drop-box locations or requiring that the drop-boxes be under the physical control of an election official. [6] For instance, one candidate for Secretary of State applauded a recent court decision limiting the use of drop-boxes. There are also proposals to ban people from dropping off ballots from their cars, a popular form of voting in 2020 when many were reluctant to enter public places for fear of catching COVID.

Some candidates would like to get rid of early voting altogether; others would like to shorten the time before Election Day during which people can cast an early ballot.

Other proposals go to the absentee ballot itself, requiring identification such as date of birth, a special early voting number or the voter’s driver’s license number for the ballot to be valid. Still other proposals include making it more difficult to correct errors on ballot, limiting the extent to which people can help a voter obtain an absentee ballot, and restricting the number of absentee ballots someone can return for others—a voter assistance practice sometimes referred to as “ballot-harvesting.” Some candidates want to make such voter assistance a crime.

Election deniers have been very suspicious of the possibility of fraudulent ballots being printed and returned by mail or dumped into drop-boxes. Hence many have called for strengthening what they refer to as “chain of custody,” which usually refers to what happens once a cast ballot is in the custody of an election administration official, but election deniers also want to tighten supply chain and anti-counterfeit techniques.

Changing how votes are counted

In 2020, state election officials in 16 states, seeing the increase in voting by mail, and worried that the post office would be slow in delivering ballots, allowed ballots to be received and counted anywhere from one day to ten days after Election Day. As noted before, more Republican voters voted in person on Election Day, and more Democratic voters voted absentee. Thus, the in-person vote in 2020 was disproportionately Republican. Many election deniers now want to restrict the time period during which absentee votes can be counted—requiring any absentee votes to be received by, or even before, Election Day.

In addition to cutting off the vote count on Election Day, deniers would like to see all ballots counted by hand and some would like to ban the use of voting machines and move to an all-paper/no DRE ballot system, although that is already pretty much required by federal law. Suspicion of voting machines runs deep among election deniers—a suspicion voiced repeatedly in Trump’s famous speech on January 6. This has led some election deniers to insist that all voting machine manufacturers turn over their hardware and software to state election officials or that ballots contain UV light activated features or be watermarked. The “chain of custody” is an important part of election integrity but, once again, there is no evidence from 2020 that anything illegal happened with ballots or that the current system is insufficient in protecting integrity.

Finally, election deniers would like to expand the use of election audits and fraud investigations. Most states conduct some type of post-election audit to verify the accuracy of their machines and their counts. A post-election audit is different than a recount, and, normally, the state limits recounts to when a race is truly close, but some election deniers are calling for more audits or for “full forensic audits”, which are more comprehensive than the routine audits done in states and significantly more expensive. Since the 2020 election, such audits have taken place in multiple states but have found nothing amiss.

One consequence of the ongoing suspicion around elections is that state election offices have also been deluged with requests for public records and requests to investigate fraudulent activity. Often these requests are overwhelming state election officials.

Changing Control of Election Results

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, some election deniers would like to change who has control over the certification of election results. The certification of elections in the United States is highly decentralized and starts at the local level where individuals can refuse to certify results. This happened in Michigan in 2020 when Republican members of a bipartisan canvassing board refused to certify the election results, delaying the state’s certification. Eventually, they reversed their decision and sent the lawful and accurate certification to the Michigan State Canvassing Board. We have since seen similar conduct by [county] election boards in Pennsylvania and New Mexico, both ultimately overwritten by the courts.

Such opportunities lay at all levels of the system. Many specific election-denier proposals would focus on giving ultimate control of election certification to state legislators. Proposed legislation in Arizona would allow a majority vote of the Legislature to “revoke the secretary of state’s issuance or certification of a presidential elector’s certificate of the election.” In December of 2020, Republicans in the Pennsylvania State Legislature introduced a measure that would allow the legislators to certify the election. In Wisconsin, a similar attempt at giving the legislature control over the presidential electors failed in court.

Even more attention has been given to the presidential election process at the point it gets to Congress for the counting of the vote of the Electoral College. Members of Congress seem ready to approve clarifying amendments to the Electoral Count Act of 1887 which would remove some of the ambiguity in the law and potentially prevent another vice president from being subject to the pressure Mike Pence was under to reject Electoral College votes.

Conclusion

The election deniers’ agenda grew out of the 2020 election when changes designed to help people vote during a historic pandemic were also used by Donald Trump to create a movement based on allegations about election fraud. Much of the election deniers’ agenda, especially in the all-important secretary of state races, focuses on vote-by-mail and early voting but there are also a wide variety of other reforms dealing with the vote count itself and the certification process that will be on the table should election deniers win these races.

The effect of this agenda on the health of democracy will vary. Reducing the number of days of early voting by a small amount may not have a serious effect although, in some of the close elections that have characterized key states of late, even a few votes at the margin can be important. Getting rid of early voting altogether and making absentee ballot access dependent on more arduous rules and regulations will probably have a disproportionately negative effect on the elderly, those who are economically disadvantaged or less educated, and young voters. Securing the chain of custody of ballots is a good idea—but states have systems in place to protect ballots and, as in other areas, there is no evidence that more is needed and putting vote certification in the hands of state legislatures is a very bad idea.

Denying the results of a fair election is threatening to the electoral process and American Democracy. We will continue our evaluation of other aspects of the election-denier agenda in future essays.

Footnotes

[1] CDC now reports the number as 1308. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailydeaths_select_00

[2] Note that there’s evidence that in the past Republicans benefited from the use of absentee ballots. See https://www.valdostadailytimes.com/news/ga_fl_news/in-southern-states-data-shows-republicans-have-a-historically-higher-use-of-mail-in-ballots/article_1d6208b6-0a57-11eb-809b-7bdd0425c41c

[3] In most of these states a voter can also vote in person. In Oregon voters can vote early at a county office and cast a provisional ballot

[4] Candidates are in the following states: AL, WY, NV, NM, ND, MN, IN, AZ, MA, MI

[5] Here is a list of the states that still require an excuse. https://www.ncsl.org/research/elections-and-campaigns/vopp-table-2-excuses-to-vote-absentee.aspx

[6] In 2016, 1 in 6 voters used a drop box for their ballots—mostly concentrated in Colorado, Oregon and Washington. https://www.npr.org/2020/08/11/901066396/ballot-drop-boxes-become-latest-front-in-voting-legal-fights

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Democracy on the ballot—what do election deniers want?

October 20, 2022