A fissure among Senate Republicans threatens federal criminal justice reform, one of the few statutory overhauls that could pass Congress in President Obama’s final year. The Sentencing Reform & Corrections Act (S. 2123), which passed the Senate Judiciary Committee last fall by the comfortable margin of 15-5, has earned support from a bi-partisan group of Senators, the White House, and political advocacy organizations ranging from Koch Industries to the American Civil Liberties Union. Senator Chuck Grassley (R-IA), the Chairman of the Judiciary Committee, has described the bill as a “truly landmark piece of legislation,” that addresses “legitimate over-incarceration concerns while targeting violent criminals and masterminds in the drug trade.”

Recently however, Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) has led a group of Republican senators in opposition of the bill. Speaking on the Senate floor earlier this week, Senator Cotton raised concerns that the Sentencing Reform and Correction Act will “reduce sentences not for those [prisoners] convicted of simple possession, but for major drug traffickers, ones who deal in hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of heroin or thousands of pounds of marijuana.” Parrying the Act’s proponents, Cotton argued that “drug-trafficking is not non-violent,” but rather part of an “industry that’s built on an entire edifice of violence, stretching from the narcoterrorists of South America to the drug-deal enforcers on our city streets.”

Over the course of its nearly 285 pages, the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act touches on many elements of the criminal justice system, from reforming sentencing guidelines for drug and violent offenders, to providing federal prisons with recidivism reduction programming, to issuing limitations on the use of juvenile solitary confinement. A Republican rift, however, appears to have crystallized around sentencing reform for federal drug offenders. The debate hinges on an implicit categorical distinction: what kinds of drug offender poses a substantial threat to public safety?

The federal prison population & U.S. population of incarcerated individuals

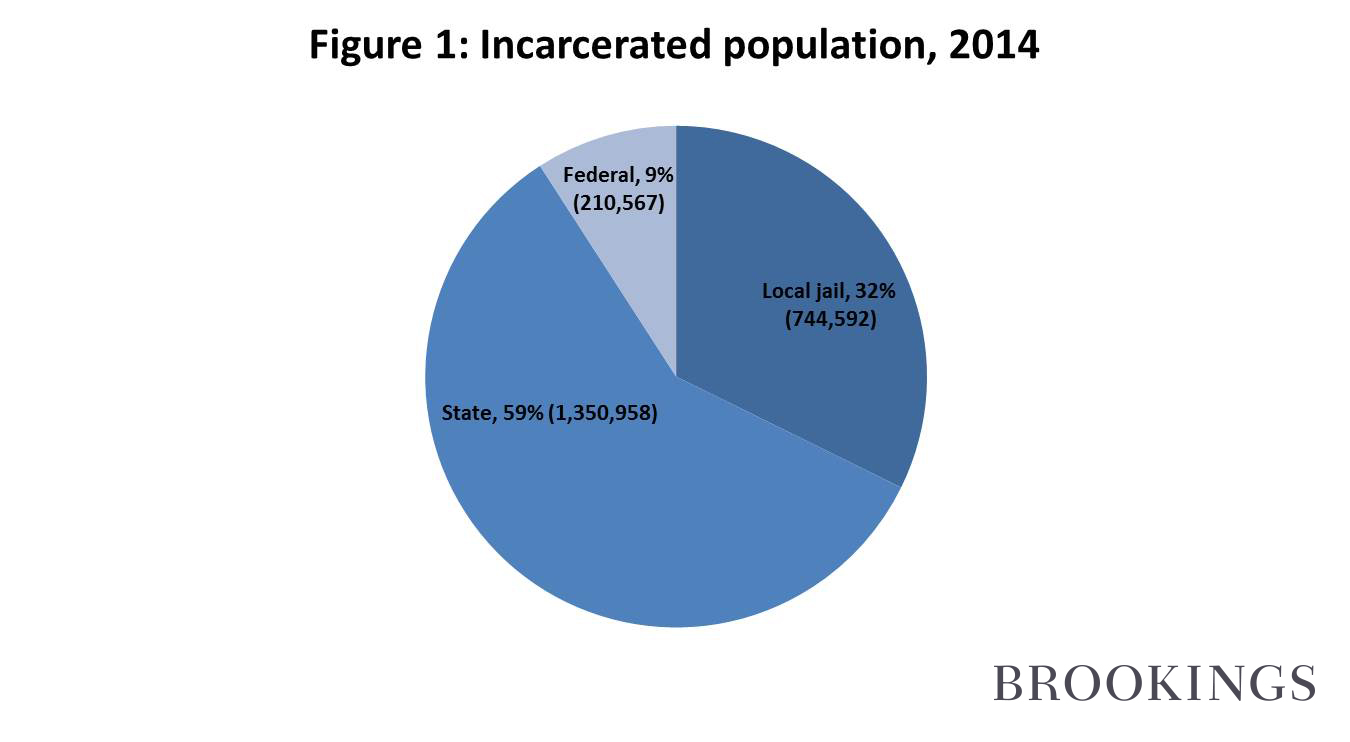

First, let us contextualize the scope and scale of the legislation at hand. The Sentencing Reform & Corrections Act is federal legislation, so it pertains only to prisoners held at the federal level. Of the more than 2.3 million individuals incarcerated in the United States, only 9% (210,567) were held at the federal level. By contrast 59% of the U.S. incarcerated population (1,350,958 individuals) is held at the state level, while the remaining 32% of the population (744,592 individuals) is held at the local level [Figure 1]. Compared to the population of individuals incarcerated in the United States in, federal level reform pertains to a relatively small number of people.

Drug crime & the federal prison population

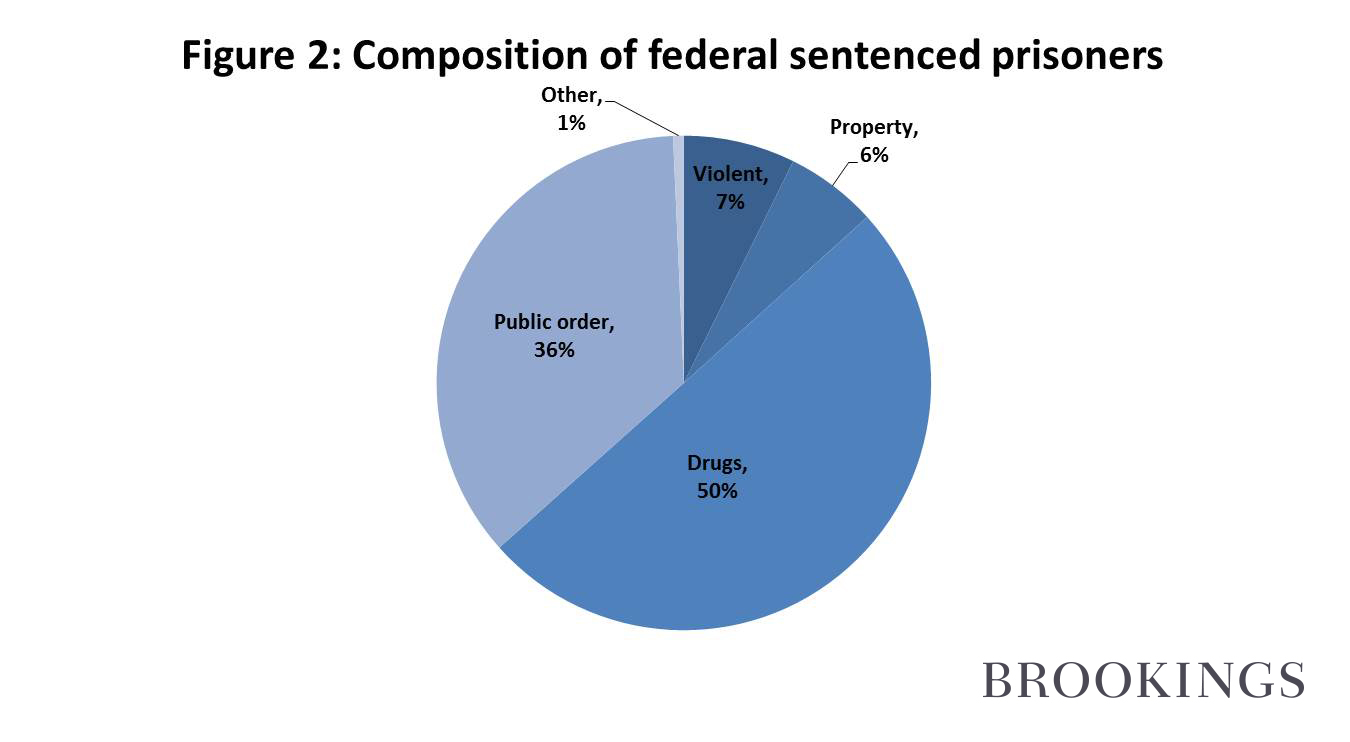

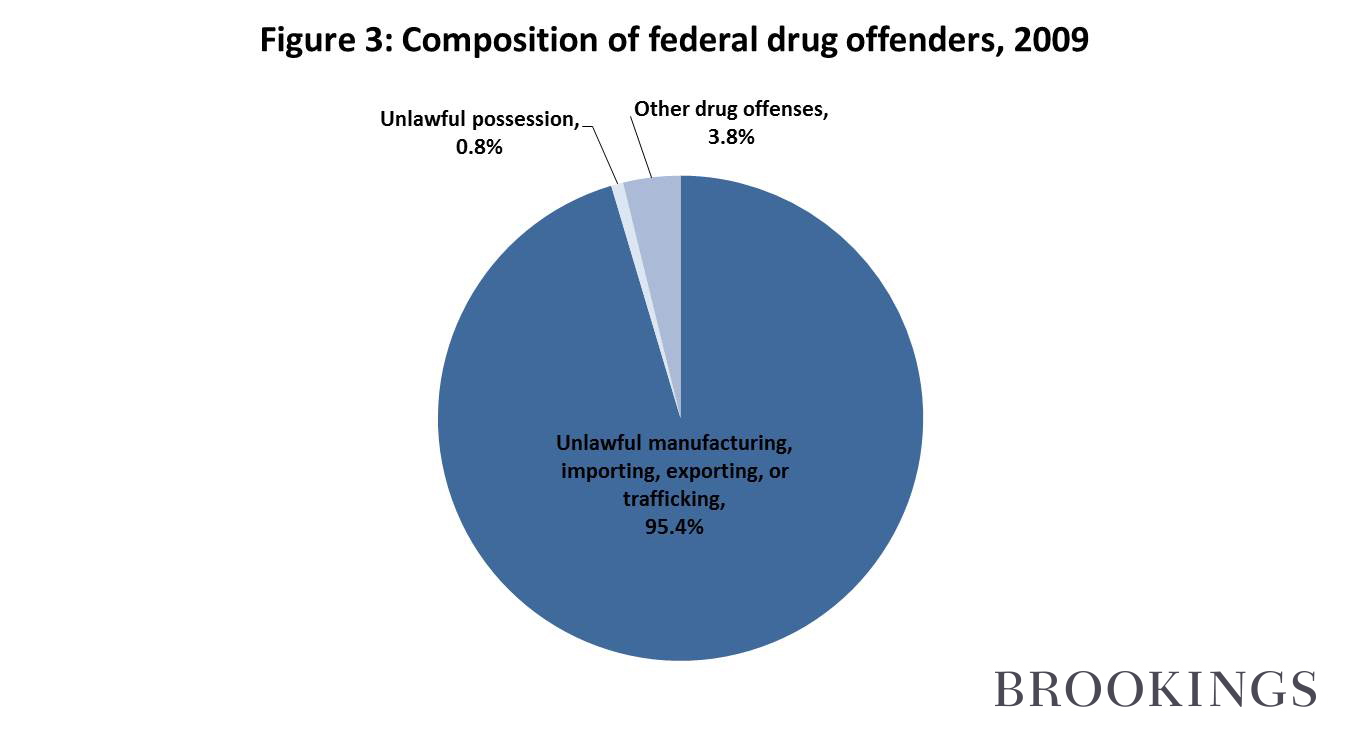

Of those 210,567 individuals incarcerated at the federal level, 50% are drug offenders [Figure 2]. The overwhelming majority (95.1%) of these offenders can be classified as drug traffickers because they were sentenced under guideline §2D1.1, “Unlawful Manufacturing, Importing, Exporting, or Trafficking (Including Possession with Intent to Commit These Offenses); Attempt or Conspiracy.” By comparison, a mere 0.8% of individuals are incarcerated for unlawful possession [Figure 3].

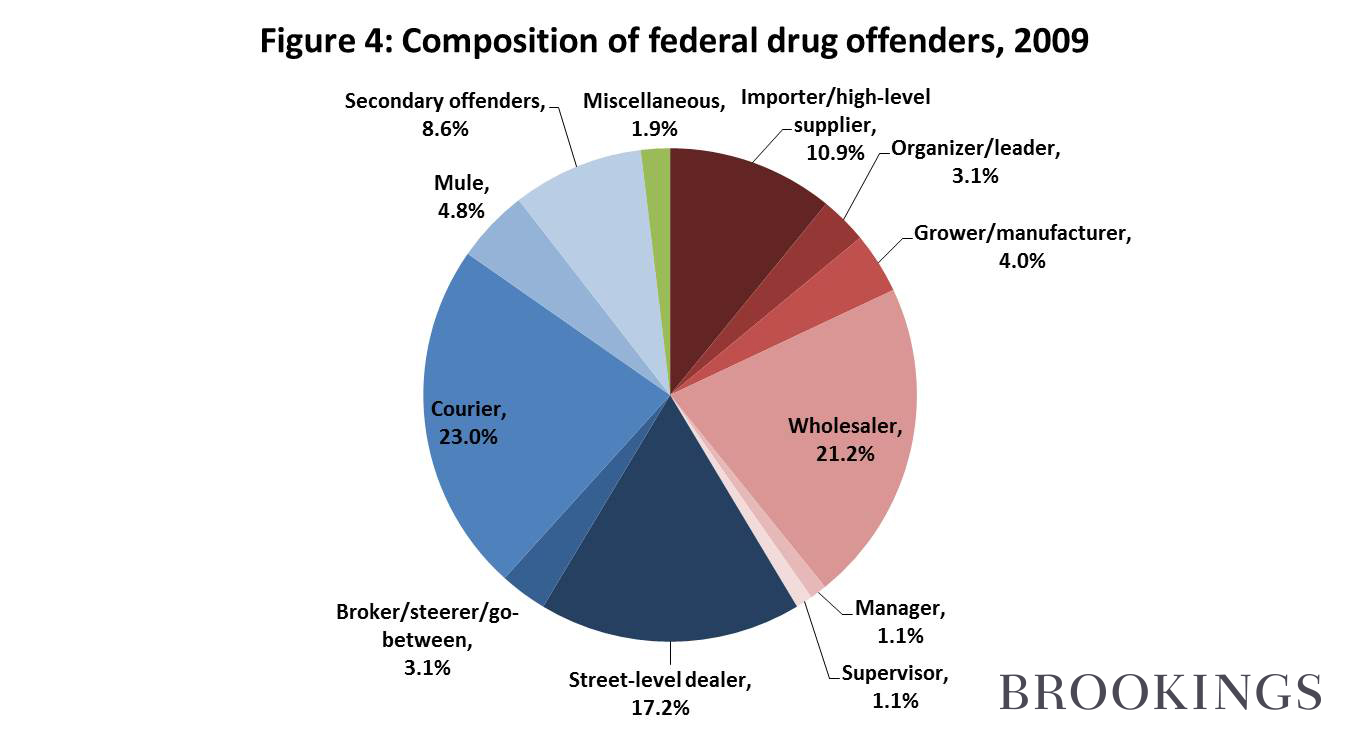

A closer examination of the data, however, tells a different story. In a recent report to Congress, the U.S. Sentencing Commission ranks the population of federal drug offenders in order of culpability by most serious offense. The categories are defined below:

- High-Level Supplier/Importer: Imports or supplies large quantities of drugs (one kilogram or more); is near the top of the distribution chain; has ownership interest in the drugs; usually supplies drugs to other drug distributors and generally does not deal in retail amounts.

- Organizer/Leader: Organizes or leads a drug distribution organization; has the largest share of the profits; possesses the most decision-making authority.

- Grower/Manufacturer: Cultivates or manufactures a controlled substance and is the principal owner of the drugs.

- Wholesaler: Sells more than retail/user-level quantities (more than one ounce) in a single transaction, purchases two or more ounces in a single transaction, or possesses two ounces or more on a single occasion, or sells any amount to another dealer for resale.

- Manager/Supervisor: Takes instruction from higher-level individual and manages a significant portion of drug business or supervises at least one other coparticipant but has limited authority.

- Street-Level Dealer: Distributes retail quantities (less than one ounce) directly to users.

- Broker/Steerer: Arranges for drug sales by directing potential buyers to potential sellers.

- Courier: Transports or carries drugs using a vehicle or other equipment.

- Mule: Transports or carries drugs internally or on his or her person.

- Secondary offenders: include offenders who were renters, loaders, lookouts, enablers, and users.

- Miscellaneous: include offenders who were pilots, captains, bodyguards, chemists, cooks, financiers, and money launderers.

Represented graphically [Figure 4], a distinction emerges: fewer than half of offenders (41.4%) are involved with the organization and/ or management of drug trade: high-level supplier/ importer, organizer/ leader, grower/ manufacturer, wholesaler, manager/ supervisor. The majority (56.7%) are low-level offenders–street level dealers, brokers/ steerers, couriers, and mules—who play who play a relatively low-level role in drug distribution.

The Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act addresses this distinction directly. Sections 102 and 103 reduce sentencing for relatively low-level offenders, but do not apply to offenders who have served as importers, exporters, high-level distributors or suppliers, wholesalers, or manufacturers. The bill also maintains a provision holding that an offender must not have used violence or a firearm or been a member of a continuing criminal enterprise, and the offense must not have resulted in death or serious bodily injury. The provision also excludes offenders with prior serious drug or serious violent convictions or offenders who distributed drugs to or with a person under the age of 18.

Conclusion

The social and economic impact of incarceration on individuals, families and communities, are substantial and well documented. As debate on criminal justice reform continues, lawmakers must ask themselves whether low-level drug offenders pose such a danger to public safety as to merit additional time behind bars.

Luke Hill and Sophie Khan contributed to this research.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Criminal justice reform: the facts about federal drug offenders

February 13, 2016