Background![]()

To assist practices and institutions throughout the country in implementing clinical redesign supported by – and aligned with – payment reform, we present a case study of the New Mexico Cancer Center (NMCC) based on numerous stakeholder interviews, literature reviews, and a comprehensive site visit. This study explores the complex barriers oncologists face in improving the quality and outcomes of cancer care and reducing overall costs in a sustainable way. This case will explore the following questions: how did the NMCC redesign care to improve quality, enhance patient experience and results, and reduce costs? How can an organization demonstrate they are improving quality to enable new payment contracts that enable sustainability? Are alternative payment models sustainable for an independent, community oncology practice?

Personal Context![]()

Vicky Bolton, a 58 year old fulltime medical legal coordinator from Albuquerque, has stage 4 adenocarcinoma lung cancer and started chemotherapy in 2003. Although her condition is stable, she is at high risk for venous thrombosis (blood clots), life-threatening infections, and other complications, which put her at high risk for repeated hospitalizations. Each of her providers and services – oncology, radiation therapy, labs, x-rays, and internal medicine – are centralized in a single location at NMCC, which has expanded, comprehensive after-hours care. In the past six months, she has taken advantage of this program on three occasions as an outpatient at NMCC and avoided emergency room and inpatient care. However, the lack of sustainable payment model has placed NMCC׳s after-hours program in jeopardy.

Problem![]()

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the U.S.1and 41% of Americans will be diagnosed with cancer at some point during their lives. Cancer care is also expensive. In 2010 it accounted for $125 billion in health care spending and is expected to cost at least $158 billion by 2020.2

The high costs of cancer care are driven by issues that plague the entire health system: uncoordinated care delivery, duplication of services, and fragmentation. A common impact of these cost drivers in oncology is the use of emergency room (ER) visits for symptom relief from the adverse side effects of treatment, which often leads to hospitalization. For example, one study showed that the most common reasons for cancer patient ER admissions were pain, respiratory distress, nausea, and vomiting – more than half of the ER visits occurred on weekends or in the evening, and over 60% resulted in hospital admission.3

The current fee-for-service payment system further exacerbates problems. Firstly, many of the clinical reforms to provide higher-value care to patients at a lower cost are reimbursed poorly if at all under fee-for-service. Secondly, to the extent that the clinical reforms reduce costly complications that are reimbursed, the financial savings accrue only to the payer, not the individual practice responsible for implementing many of the reforms.

Catalyst for Change![]()

Dr. Barbara McAneny founded the New Mexico Cancer Center (NMCC) in 1987 and in her years working as a medical oncologist, she has been particularly frustrated by the adverse impact that fragmented care has had on her patients. Often patients are directed to up to three different locations to receive care from their oncologist, lab tests, and chemotherapy treatments. NMCC created an independent, free-standing, integrated community cancer center designed around patient needs.

Solution![]()

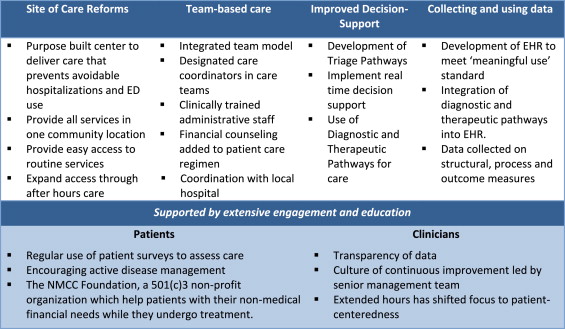

In this study, we use a care redesign framework (Fig. 1) to consider the specific elements undertaken by NMCC as they improve quality patient-centered care at a reduced cost.

Fig. 1: Care redesign framework

Care redesign strategies![]()

Over the past 15 years, NMCC has redesigned where care is delivered; who care is delivered by; how care decisions are made; and the data used to ensure effectiveness (see Fig. 2). To make these intended transformations ‘come alive’, extensive engagement has been undertaken with both patients and clinicians.

Fig. 2: Care redesign elements undertaken by NMCC.

Purpose built center to deliver care

NMCC bought land to build their center in 2001 and the patient perspective had an impact in all areas of buidling design and décor. The center itself is a single-story building with a parking lot right outside so that patients do not need to walk a long way to and from their treatments. The internal layout of the building has also been specifically designed to feel more like home, less like an austere, health care institution. The doctors offices are arranged in 3 ‘pods’ with a central desk with medical assistants to support patients and clinicans, rather than one large and overwhelming office.

Provide all services in one community location

Geographic clustering of care can lead to better patient satisfaction and a reduction in unnecessary duplication of service through improved compliance with medication administration, lab testing, and follow-up. By having everything from diagnostic imaging to lab services and chemotherapy all available in one place, NMCC has created a centrally located hub for services, instead of forcing patients across multiple providers and sites of care. By providing this all in a community setting ensures that the rates paid for services are lower than they would be in a hospital inpatient or outpatient department. For example, the cost of receiving chemotherapy, per beneficiary, in a hospital was 25–47% higher than in a physician office from 2009 to 2011.4

Designated care coordinators in care teams

Each physician is paired with a patient care coordinator (PCC) and they share a case-load. The PCC takes all routine non-clinical work from the doctor so that they can work at the top of their license. They also work with patients and book all appointments, schedule required treatments, and arrange travel when needed. This helps reduce delays in treatment and allows the patient to focus solely on their treatment and recovery.

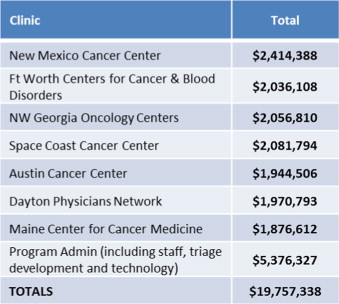

Funding strategy

Most of these redesign initiatives did not have direct financial support and funding came from reinvestment of NMCC profits in the early 2000s. Following failed attempts to secure payer funding for enhanced services, additional financial support came in 2012 from a $19.8 million grant awarded by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) to NMCC and six other oncology practices for a program called COME HOME (see Fig. 3 and Fig. 4). The program is tasked with demonstrating improved outcomes, enhanced patient care, and lowered costs, and has an explicit aim to reduce ER visits by 50% and hospitalization by 20% to justify the program costs.

Fig. 3.

Breakdown of grant allocation by cost category.

Source: information provided by NMCC and COME Home Innovative Oncology Business Solutions, Inc. staffs through emails following interviews.

Fig. 4.

Breakdown of grant allocation by clinic.

Source: information provided by NMCC and COME Home Innovative Oncology Business Solutions, Inc. staffs through emails following interviews.

The major areas of redesign through the COME Home program were the extended hours of practice and improved triage decision-support.

Expand access through after hours care

Prior to the project, NMCC closed at 5 pm on weekdays and offered no weekend hours. The center is now open until 8pm on weekdays and 1–4 pm on weekends. In addition to the physicians and nurses operating at these times, the in-house lab is also open to ensure that physicians have access to the tests and test results required to treat patients effectively. To help manage this as effectively as possible, NMCCs hired an urgent care physician to treat patients experiencing side-effects. Prior to the implementation of the filgastrim (Neupogen) shot clinic on weekends, patients had to visit an emergency department or inpatient facility to receive shots, pay high drug- and visit-copayments, and often wait several hours in an environment with high risk of infection from other ill patients. At the end of quarter seven of operation, NMCC has averaged 82 extended hours׳ visits per month accounting for approximately 14% of all patient visits.

Improved decision support

NMCC has worked to improve their decision-support for both physicians and nursing staff. The physician support has been focused on diagnostic and therapeutic pathways (intend to guide physicians toward the most effective treatments, and in the event that two treatments have the same efficacy, toward the least expensive one) and the nursing support has been in the triage pathways.

NMCC now have clinical (diagnostic and therapeutic) pathways for seven tumor types, which account for 75% of their patients. They are currently at 80% adherence to their pathways and have started to look at other measures for diagnostic and therapeutic excellence.

The triage pathways support decision making when patients call with acute symptoms or questions. Previously, only experienced oncology registers nurses (RNs) and licenses practical nurses (LPNs) provided patient assistance via telephone, limited to the hours of 8 am and 5 pm, and there were no formal written processes in place. This led to lengthy calls with patients, variation in the information patients were given, and possible preventable visits to ERs and hospitalizations.

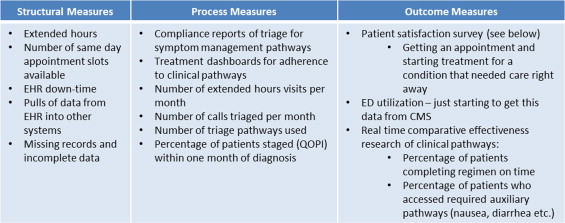

Collecting and using data

Before any data is collected, NMCC develop a schema outlining the intended use and the decisions it will underpin (clinical actions to improve care). Quality measures are not considered static and, once achieved, are amended with more rigorous targets (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Key measures collected by NMCC.

NMCC would like to use claims data from CMS and other payers to help identify opportunities for improvements in care, but they have not managed to solve some of the key data sharing issues involved, including privacy concerns and the timely access to information.

Patient surveys

NMCC uses a patient satisfaction survey developed by Community Oncology Alliance (COA), based on the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) methodology.5 The COA survey includes questions that could be turned into quality measures for actionable data. Three areas of focus include whether patients received their care right away, whether patients received all the information they wanted about their health to share in decision making, and whether patients felt they were treated them with respect.

Technology

NMCC׳s EHR is Varian׳s ARIA. It was originally purchased, as part of NMCC׳s profit reinvestment in the early 2000s, for $450,000 and the practice spends $500,000 annually for licenses and maintenance. The diagnostic, therapeutic, and triage pathways are integrated into the EHR and provides near to real-time reporting (with twice-daily data sync). Recent improvements to the system include ability to input DNR discussions (a key quality metric), co-morbidities, and family history. NMCC took into account “meaningful use” requirements when designing the specifications for their EHR – the federal legislation that ties incentive payments to using certified EHR technology and adopting required objectives and measures. In future enhancements, NMCC are aiming to develop predictive analysis to target interventions.

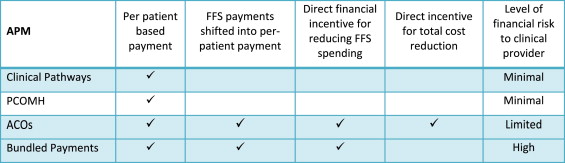

Alternative payment models (APMs) to sustain care redesign![]()

Fig. 6 describes APMs in development for oncology are in the early stages but all, to varying degrees, work towards transitioning to a more comprehensive episode- or case-based payment, and reducing or limiting FFS payments for some services, in order to enable more financial support for the types of care redesign activities that are not reimbursed under FFS.6

Fig. 6.

Comparison of alternative payment models for oncology.

Payment for clinical pathways adherence

Clinical pathways, based on National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines, are considered by many to be the first step towards a more comprehensive payment and delivery reform option in oncology. The other alternative payment models described below include adherence to pathways as part of their reform.

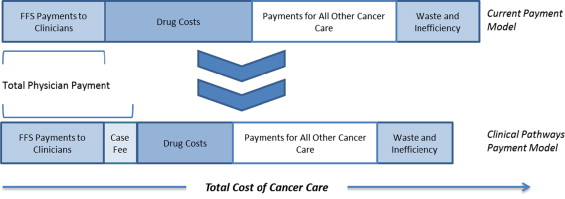

The clinical pathways model itself uses an add-on per-patient payment to encourage adherence to predefined, evidence-based chemotherapy regimens. A provider adopts clinical pathways into their workflow and, in doing so, agrees to use a preselected group of triage, diagnostic, and/or therapeutic treatments; for treatments that have been shown to be equal in clinical effectiveness (and minimizing side effects), the clinical pathways will recommend the treatment with the lowest cost (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Reduction in overall cancer costs through implementation of clinical pathways.

Preliminary findings from pilot studies of clinical pathways suggest the initiatives have had an impact on costs without worsened outcomes. One study of a cohort of lung cancer patients showed a reduction in drug costs of 37% over the course of the 12 month study. A majority of these savings were associated with adjuvant and first-line chemotherapy drugs with no cost saving found in second-line settings.7 A more conservative cost reduction estimate comes from WellPoint, which recently begun offering oncologists a $350 per-member-per-month payment for each cancer patient on a pathway, and estimates 3–4% reductions in treatments costs per year.8

Potential opportunities and barriers of clinical pathways for a community oncology practice

While clinical pathways do require commitment from physicians to develop and update, they do not require major structural changes to implement. They therefore represent a good starting place for a practice to start to reduce variation between individual physicians and potentially reduced costs. The major barrier to using clinical pathways as a payment model is whether a practice can find a payer who is willing pay a case fee for compliance to standard.

A practice may choose to view clinical pathways not as an APM in itself, but as an important quality initiative which will provide assurance to payers to underpin other alternative payment models.

Patient-centered oncology medical home

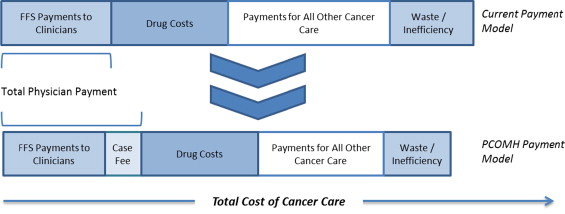

The PCOMH includes a fixed PMPM fee for clinicians that meet a specific set of capabilities and quality standards in their practices, using an adaptation of the primary care patient-centered medical home framework established by the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA). This fee can be used to support services not reimbursed by FFS of for infrastructure investments such as additional staff time for patient care, care coordination, and better decision support for care management.

The initiation of the payment model begins with a patient׳s diagnosis and the case payment in oncology is generally between $200 and $250 PMPM which is significantly higher than the $5–20 PMPM received in primary care due to the additional complexity of the care delivered to cancer patients.6 (Fig. 8)

Fig. 8.

Reduction in overall cancer costs through implementation of a PCOMH.

Preliminary findings from of care and cost savings from PCOMHs have been promising. The most well-known PCOMH is pioneered by Dr. John Sprandio and his colleagues at the Consultants in Medical Oncology and Hematology (CMOH), a small physician practice outside of Philadelphia. In 2010, CMOH was the first oncology practice to be recognized by the NCQA as a level III PCMH.9

Early results showed that ED visits at the practice fell by 68%, hospital admissions per patient treated with chemotherapy fell by 51%, and the length of stay for admitted patients fell by 21%10 and 6. CMOH estimates that the aggregated savings to CMOH payers is approximately $1 million per physician per year through reductions in the cost of care for the clinically vulnerable-patients that are older, chronically ill, and with multiple comorbidities.

Potential opportunities and barriers of PCOMHs for a community oncology practice

A practice which already redesigned care to a medical home model would be well positioned to implement this payment model. However, establishing the required PMPM or the amount the practice could save the overall system if ER visits and hospitalizations are reduced will be almost impossible without access to claims data from both commercial and federal payers. Practices that have not yet redesigned care may find that, without clear evidence that the up-front payment will lead to quality improvements that succeed in reducing overall costs of care, may find payers to be reluctant to agree to the additional payments required to implement the required changed.

Further, even if the data issues facing a particular payer can be addressed, it is necessary that a payer must have enough market share to act alone and sustain the payment model. The medical home is difficult to implement for only one payer׳s patients, for both technical and professional practice reasons. If only one payer implemented the payment reform, the PMPM for supporting the medical home would apply to only a fraction of patients, making it difficult to sustain the costs of maintaining medical home services and capabilities for their entire practice.

Oncology accountable care organizations (ACO)

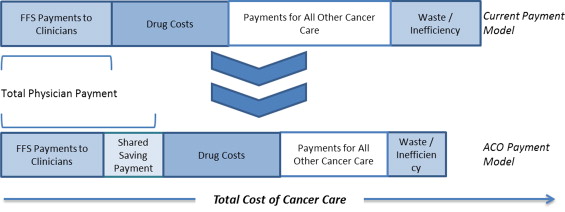

The oncology ACO framework introduces a shared saving model based on overall patient costs and quality of care in addition to FFS reimbursement. It builds on this alternative payment approach over time with an aim to moving more reimbursement from FFS towards a partially capitated payment for a broader range of oncology services. A group of providers are held accountable for the overall quality, cost, and care of their patient population and share the savings recouped form better coordinated, higher quality care (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Reduction in overall cancer costs through implementation of an ACO.

Two early oncology ACO models were developed in Florida with the local BCBS health plan, Florida Blue. The first was a joint program between Baptist Health South Florida and Advanced Medical Specialties, and the second was with Moffitt Cancer Center. There are approximately 1000 patients across both ACOs and the model stratifies risk only by type of cancer. The models target the overall cost of care, not just their oncology care, running for one year from first diagnosis.11

One key challenge to developing these models was defining measurements – particularly how to define and attribute cancer cases. The sharing of data between provider and payer was crucial and outside counsel was required to address these and other issues (e.g., data privacy protections). The solution reached was to consider full utilization except mental and behavioral health and utilization and spending benchmarks were developed by actuaries within Florida Blue.

The results of these models have included early clinical successes, with significant reductions in hospital admissions and readmissions, better generic drug prescribing rates, greater adherence to pathway and evidence-based protocols, and better coordinated care.12 The financial successes are less clear and, because of variations in costs of care, are difficult to discern with high statistical confidence.

Potential opportunities and barriers of ACOs for a community oncology practice

To become part of a successful ACO, a practice must form part of a large, cohesive, coordinated network which can share data to attribute patients and shared savings appropriately6. Locating ACO partners will be a challenge for any community oncology practice if, as in Albuquerque, there is a large integrated health system with its own hospital-based oncology practice in the local area.

Bundled payments

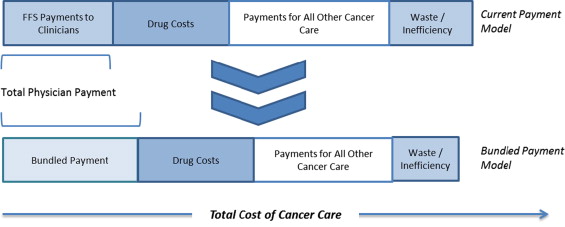

A bundled payment is a combined payment for a package of clinically related services in a case or episode of care, including multiple services from a particular provider or the services of multiple providers. The bundled payment may be a fixed price paid prospectively, or a benchmark that is used to adjust net payments to the providers retrospectively. It is designed to appropriately compensate clinicians for the comprehensive set of services required to meet patient׳s needs for the episode of care, as opposed to billing for each individual test, procedure, and service provided. Bundled payment enables clinicians to redirect resources to services that are not currently compensated, and requires clinicians to take accountability for the overall cost of the episode (Fig. 10).

Bundled proposals for oncology include a pilot focusing on multi-practice episode-based payment for chemotherapy drug administration (United Healthcare13) pilots for a broader set of bundled services for specific cancer types (Fox Chase and Horizon BCBS14, and 21st Century Oncology and Humana15), and a pilot for bundling radical prostatectomy early stage patients (Mobile Surgery International and Florida Blue). Most of these pilots involve limited or partial shifts of FFS payments into episode-based payments. While CMMI is exploring bundled payment options for acute and post-acute care through the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative, the payment options do not include or target comprehensive cancer care.16

Potential opportunities and barriers of bundled payments for a community oncology practice

To be able to develop a bundle of services, a practice must be able to assess the extent to which it could take on accountability for the costs of services provided. Payers need to be both able and willing to share this information so that complete claims data can be used to analyze costs, and practices need the actuarial capacity to analyze this data appropriately.

Additionally, early understanding of which patients and services do or do not fit into a bundle is challenging, especially for broader bundled payments, and would require near-to real-time monitoring across the network for providers included in the bundle. Implementing a broad bundle is made even more complex by the fact that treatments are constantly developing and changing – treatments that are standard now may be quite different in a year׳s time.

While some organizations have begun work on creating comprehensive bundled payments for cancer, only more limited bundled payment pilots like those described above are currently in operation. These limited payment reforms may not be sufficient to support the major care reforms envisioned by a practice to achieve better outcomes and substantial savings. However, implementing an oncology medical home with supporting payment could be a basis for developing the data and systems needed to support effective implementation of bundled payment.

Recommendations for NMCC![]()

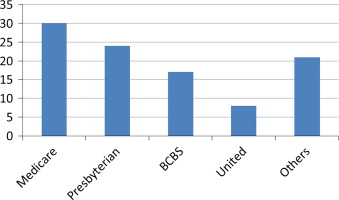

The goal for NMCC is to find a payment model to recover the amount of initial investment and support the continued efforts of the COME HOME program to provide services to all of NMCC׳s patient population, not only those of a particular payer. Because no single payer has a substantial market share (see Fig. 11), payers may be reluctant to subsidize a service which could potentially be underwritten by another payer.

Fig. 11.

Breakdown of Payers NMCC. NOTES: medicare is only accounting for payments received from the government; Presbyterian׳s figure includes Medicare Advantage, Managed Medicaid and commercial; Blue Cross Blue Shield׳s (BCBS) includes Managed Medicaid and commercial; Indian Health Service (IHS) is significant in Gallup but not in overall market.

Source: information provided through interviews with NMCC staff.

Of payment reform options, NMCC has been unable to contract as part of a comprehensive ACO due to local health care market conditions. Clinical pathways are geared primarily to guidelines and chemotherapy adherence, and are not designed to provide funding for after-hours care or triage programs that are intended to achieve offsetting savings through avoiding costly complications. Possible remaining options include the following:

Option 1: PCOMH with accountability

Using the data it gathers, NMCC intends to quantify the additional costs the COME HOME model requires, and the savings that it achieves. Using that estimate, NMCC could suggest a per-member per-month (PMPM) payment from a private insurer to cover the costs of providing higher quality care. To encourage participation, NMCC could also enter into a risk-sharing agreement, in which overall costs of inpatient care and ER visits would be compared against a target. The PMPM could be at-risk if the targets are not achieved after a certain period of time.

Option 2: PCOMH with accountability to support transition toward bundled payment

While an oncology bundled payment is NMCC׳s long-term preferred model, an interim possibility might be to use the medical home approach with risk sharing (described above) as a first step toward a bundled payment system. Computing actuarially sound expected costs for the bundled payments would require merging claims data with clinical data (for example, ICD-9 codes fail to distinguish between subtypes of breast cancer that have radically different treatments). A limited bundled payment pilot might be performed initially for high volume cancers, such as breast and lung.

Option 3: enhanced FFS through public or private insurance

NMCC could seek to modify the existing model with enhanced fee-for-service payments to cover out of hours visits and telephone-based triage services. However, this simply adds to the fee-for-service arrangements, and payers may be reluctant to support due to concerns that it would primarily generate additional billing rather than better care coordination, care transformation, and reductions in overall costs.

Option 4: direct contracting with major employers

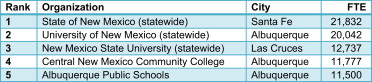

Finally, given the challenges of working with payers in its market, NMCC could consider directly contracting for oncology services (known as a carve out) with major employers (see Fig. 12 for a list of the top employers). There is a precedent, in which Intel has entered into an ACO-type arrangement with Presbyterian Hospital to provide medical services to employees through the group health insurance sponsored by the employer.

Fig. 12.

Top five employers in New Mexico, 2011.

Source: NewMexicoNetLinks, Largest Employers in New Mexico. 17

Lessons![]()

The experience of innovative pioneers like NMCC can shed some light on potential barriers to conceptualizing and implementing sustainable clinical redesign.

Relationships with payers and network

NMCC׳s experience illustrates that a prolonged commitment to demonstrating significant value from care redesign, particularly from lower utilization of inpatient and emergency department utilization, does not automatically create a financial pathway for sustainable delivery reform. Innovative providers that seek to reform care should consider a sustainability path from the start. This might include involving lead payer partners early on to help identify end-points of interest to payers and potential payment alternatives to traditional fee-for-service payment that could support these reforms.

Providing support for health care delivery reforms requires new activities by payers towards sharing data in new ways to enable care improvements to be prioritized and implemented, and aligning their payments with value, rather than volume and intensity of services. However, fragmented health care markets face challenges of the “free rider” problem (that is, payers may be unwilling to shoulder delivery transformation costs that may benefit other payers׳ clients, and wait for CMS or others to make the financial investment, pay for the program evaluation, and enact policy change), payer inertia, and long lag times between care redesign and subsequent data demonstrating results.

Large ACOs and other integrated payer-provider plans, including those large enough to form Medicare Advantage plans, are moving forward on negotiating payment and delivery reforms. This may be more difficult for innovative, smaller practices, even if they can provide higher-value clinical services. However, reliance on very large providers may have anti-competitive consequences, such as discouraging delivery innovation that leads to “demand destruction” of high-cost hospital-based services.

For this reason, private and public payers should be particularly interested in developing models that enable smaller, specialized providers like oncology practices to undertake key delivery reforms. Such specialty-specific payment models should be a high priority for CMS and regional or national collaborations on payment reform involving multiple private payers.

Payment model selection

While substantial attention has been paid to primary care focused APMs, specialty-focused APMs are needed for practices like NMCC. Their development should be a high priority for public and private payers.

Clinical transformation grants, such as those offered by CMMI, should include clear pathways for transitioning to APMs if initial quality improvement and cost savings targets are met. Otherwise, delivery system innovations are at high risk of failure despite evidence of improved value. Another approach to help assure sustainability is for grants to require evidence of early payer engagement with delivery transformation efforts, and early implementation of key steps like the use of standard measures that could be a basis for APMs. Organizations such as ASCO have offered policy solutions for payment reform which could apply to both public and private payers as well incorporating elements of bundled/episodic payments.18 These or other models now being implemented could provide a good foundation for “best practices” for smaller practices and payers to use to implement delivery and payment reforms at a much lower cost.

Data collection and quality improvement considerations

Timely sharing of actionable information from claims and other administrative data remains a major challenge, with complex and varied procedures for obtaining claims from payers, and challenges especially for smaller practices in interpreting the claims data. Some states, such as Maryland, Massachusetts, Vermont, and Colorado (among others) are proceeding with creating all-payer claims databases.19 Maryland, for example, offers rapid provider feedback on some key information for patient management from claims through their CRISP database.20 Payers could also provide such data to innovative practices directly, to build trust and provide a needed foundation for payment and delivery reform.

In addition to producing performance measures from claims data, more progress is needed to provide timely and actionable data to enable practices to improve performance. As NMCC׳s early efforts illustrate, practices can produce more clinically sophisticated performance measures using the same clinical support systems that enable improved patient care.

Conclusion![]()

Unfortunately those at the leading edge of change in the last decade are not necessarily in the position to benefit most from payment reform – they׳ve already done a lot and there is relatively little low-hanging fruit – payers do not want to have pay for changes already made. In fact, diminishing returns to quality improvement activities may actually be less costly for providers at a low baseline level or performance that for one at a high level (NMCC) to improve quality.21 These means that providers who have either not engaged in significant delivery reform or those whose prices are already far above market averages stand to benefit the most from shared-saving arrangements, which tend to penalize those who already work efficiently. It also means that providers with high quality and low baseline costs must work that much harder if incentives are based on quality improvement as opposed to absolute quality.

Acknowledgment![]()

We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Richard Merkin and The Merkin Family Foundation for their support of this publication, and for supporting the Engelberg Center for Health Care Reform׳s policy leadership of innovations in care delivery and payment reform.

References

1. American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2014. Retrieved from: 〈http://http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/webcontent/acspc-042151.pdf〉; 2013

2. A. Jemal, R.C. Tiwari, T. Murray, et al.

Cancer statistics, 2004

(Retrieved from) CA: Cancer J Clin, 54 (1) (2004), pp. 8–29 〈http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14974761〉

3. D.K. Mayer, D Traver, A Wyss, A Leak, A. Waller

Why do patients with cancer visit emergency dpeartments? Results of a 2008 population study in North Carolina J Clin Oncol, 29 (19) (2011), pp. 2683–2688 http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.34.2816

4. The Moran Company. Cost Differences in Cancer Care Across Settings. Retrieved from 〈http://www.communityoncology.org/UserFiles/Moran_Cost_Site_Differences_Study_P2.pdf〉; 2013

5. Oncology Medical Home. Patient Satisfaction. From: 〈http://www.medicalhomeoncology.org/coa/patient-satisfaction.htm〉; 2013 June 25. Retrieved 20.07.14.

6. McClellan M, Patel K, O׳Shea J, Nadel, J., Thoumi, A., & Tobin, J. Specialty Payment Model Opportunities Assessment and Design: Environmental Scan for Oncology (Task 2), Final Version. Retrieved from The Brookings Institution and MITRE website: 〈http://www2.mitre.org/public/payment_models/Brookings_Oncology_TEP_Environ_Scan.pdf〉; 2013

7. Fitch K, Iwasaki K., Pyenson B. Comparing Episode of Cancer Care Costs in Different Settings: An Actuarial Analysis of Patients Receiving Chemotherapy. Retrieved from Milliman website: 〈http://www.communityoncology.org/UserFiles/Milliman_SiteCostofCancerStudy_2013.pdf〉; 2013.

8. A.W. Mathews Insurers push to rein in spending on cancer care

Wall Street J (2014) A1. Retrieved from: 〈http://online.wsj.com/articles/insurer-to-reward-cancer-doctors-for-adhering-to-regimens-1401220033〉 [28.05.14]

9. Conway L. The Advisory Board Company – Good Call: Oncology Practice׳s Phone Triage Curbs ED visits. Retrieved July 21, 2014, from 〈http://www.advisory.com/research/oncology-roundtable/expert-insights/2012/good-call-oncology-practices-phone-triage-curbs-ed-visits〉; 2012.

10. J.D. Sprandio Oncology patient-centered medical home

J Oncol Pract, 8 (3) (2012), pp. 47s–49s http://dx.doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2012.000590

11. Haasis B, Parzik R. Florida Blues. Interview by Darshak Sanghavi [Personal interview] Paying for Cancer Care; 2014, June 3.

12. Edlin M. Oncology ACOs offer innovation for high-cost populations. Managed Healthcare Executive. Retrieved from: 〈http://managedhealthcareexecutive.modernmedicine.com/managed-healthcare-executive/news/oncology-acos-offer-innovation-high-cost-populations?contextCategoryId=21〉; 2014, January 1.

13. Newcomer, L. Interview by J. Marcille [Personal Interview]. a conversation with lee newcomer. mha: payments with purpose. Managed Care. Retrieved from: 〈http://www.managedcaremag.com/content/conversation-lee-n-newcomer-md-mha-payments-purpose〉; 2011, December.

14. Peskin S., Sobczak M. Innovative cancer care initiative #3: Transitioning to risk-episodes and bundles. Powerpoint Presentation and Panel Discussion at 2013 Cancer Center Business Summit, Transforming Oncology Through Innovation. 〈http://www.cancerbusinesssummit.com/presentations/Thursday/245PMICCI3TransitioningtoRiskFINAL.pptx〉; 2013.

15. B. BandellBlue Cross signs first bundled payment deal with Miami firm

(Retrieved from) South Florida Bus J (2011) 〈http://www.bizjournals.com/southflorida/print-edition/2011/04/08/blue-cross-signs-first-bundled.html?page=al〉

16. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Department of Health and Human Services.. Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) Initiative: General Information. from 〈http://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments/〉; n.d. Retrieved 21.07.14.

17. Sacco S. Largest Employers in New Mexico (with 150 or more FTEs). From 〈http://http://nmnetlinks.com/cms/kunde/rts/nmnetlinkscom/docs/1044065435-01-19-2011-18-16-39/xls_upload.htm〉; 2011, January 11. Retrieved 21.07.14.

18. American Society of Clinical Oncology. Consolidated Payments for Oncology Care: Payment Reform to Support Patient-centered Care for Cancer. Retrieved from: 〈http://www.asco.org/sites/www.asco.org/files/consolidatedpaymentsforoncologycare_public_comment_06.20.14.pdf〉; 2014.

19. Green L, Lischko A, Bernstein T. Realizing the Potential of All-payer Claims Databases: Creating the Reporting Plan. Retrieved from Robert Wood Johnson Foundation website: 〈http://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2014/rwjf409989〉; 2014.

20. Chesapeake Regional Information System for Our Patients. CRISP: Prepare for the Future of Healthcare. From 〈http://crisphealth.org/〉; n.d. Retrieved 21.08.14.

21. George M, Sanghavi, D.. Advancing Care for Vulnerable Newborns: The role of Regional Collaboratives [Web log post]. Retrieved from 〈https://www.brookings.edu/blogs/up-front/posts/2014/06/03-premature-nicu-infant-mortality-sanghavi〉; 2014, June 3.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Case Study: Transforming Cancer Care at a Community Oncology Practice

July 5, 2014