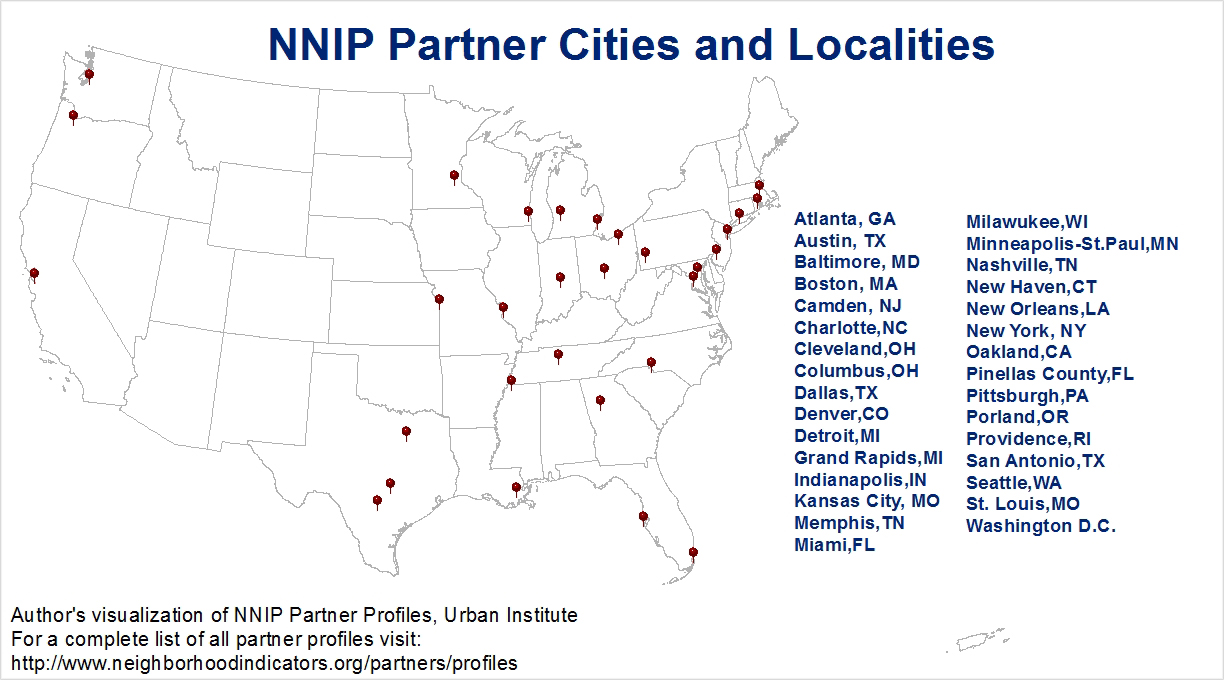

The National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP) is a peer-learning network of organizations in 30 cities, coordinated by the Urban Institute. Local partners collect and organize neighborhood-level data and help community organizations, foundations, and local government use the information for community building, policymaking and advocacy, empowering residents and community groups in low-income neighborhoods to use data to help shape policy.

Kathryn Pettit is the director of the NNIP and a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Center at the Urban Institute, where her research focuses on measuring and understanding neighborhood change.

When did the NNIP start? What motivated it?

The “NNIP model,” which organizes and shares neighborhood-level data to inform community improvement efforts, was pioneered by Claudia Coulton in Cleveland at Case Western Reserve University in the early 1990s. At the time, very little information was available about neighborhoods, and indicators at the city level had little value to support the emerging community development field. Collecting and creating indicators from local administrative data, such as property records, crime reports, and vital statistics, helped inform and guide strategies for comprehensive community change. In the early ‘90s, Cleveland along with other groups in Atlanta, Boston, Denver, Oakland, and Providence were funded by Jim Gibson at the Rockefeller Foundation through their Community Planning and Action Program to use data for community organizing. These groups met several times to discuss their work and learn from each other. They approached the Urban Institute in 1995 to conduct a study of the usefulness of the model and develop plans to expand the work to other cities. The study confirmed the value of the approach and the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership was formed in 1996, with the Urban Institute as the network’s home. The network’s principles aligned well with Urban’s mission to build an evidence base to reduce hardship amongst the most vulnerable, expand opportunities for all people, and strengthen the effectiveness of the public sector.

The NNIP website lists 31 cities in the network, with a diverse mix of nonprofit organizations, university/research centers, community foundations and local government agencies. How were these organizations selected, and what are key requirements for joining NNIP?

All cities could benefit from services of an NNIP partner and we are coaching organizations in several new cities that are interested in joining the network. Organizations that wish to join NNIP and represent a city in the network need to fulfill three basic criteria: 1) build, operate, and recurrently update neighborhood-level data on a variety of issues; 2) help community organizations, local government, and foundations use the data for better decision making, program planning, etc.; and 3) focus on building the capacity of institutions and residents in low-income communities to use data. In most NNIP cities there is only one partner organization, but there are a number of places, like in Charlotte, where several organizations have joined together to collectively fulfill the three basic criteria of an NNIP partner. In addition to commitment to the three basic functions above, the network looks for organizations that are trusted by community groups and local government, have the staff capacity to process and analyze data, and have experience helping local organizations to use data. The network has a rigorous application process that includes a review by our elected Executive Committee.

Among the key aims of the NNIP, you cite the building of free information systems with integrated and recurrently updated information on neighborhood conditions. Is there a blueprint organizations have followed for building these systems? What have been some of the key challenges partners have encountered in building these systems?

There is not a single blueprint for this type of work, but we have many lessons from the past 20 years in our cities. Partners strategically acquire new data sources based on community priorities and then maintain and update them going forward. It takes a number of years for an organization to acquire data across a variety of domains. The advent of open data has sped up the process for some publicly available data sources, such as crime and property records, and many of our partners are active in advocating for the release of more government data. However, open data does not cover confidential data sources such as school records, food stamp rolls, and vital statistics, which require data-use agreements to protect how the data is stored and used. These relationships develop over time as data providers learn to trust that the NNIP partner organization can responsibly handle the data. Some agencies may be reluctant to share data or not be aware of how useful it could be for work outside of the agency. We have developed a brief guide to data sharing that gives advice on negotiating for data access based on NNIP experiences.

What have been some of the major accomplishments of the network and local partners? How do you measure success?

The greatest success of the network is the increased level of sophistication of our partners and the spread of the model to many more cities. For our local partners, success is measured in the influence they have on their local audiences and collaborators—more informed deliberations and decisions that result in better communities for everyone. Success might be convening a cross-sector group of stakeholders around an issue like school readiness for the first time, or helping the school district develop a system to monitor chronic absenteeism, or motivating a change in city regulations around how investors maintain and register their properties.

At the network level, the Urban Institute and its local partners have fostered a successful community of practice in which partners are actively engaged to strengthen the network and support each other. We have also launched about a dozen cross-site projects, which encourage the partners to expand into new areas, such as prisoner reentry, school readiness, integrated data systems, and open data.

Over the next few years, what are some of the objectives you are hoping to accomplish with NNIP? What lessons or recommendations do you have for organizations that are hoping to venture into the realm of using data to foster community change?

As a network, NNIP will continue to support our current partners and expand the NNIP model to new cities and to build broad support for using community-level information in decision-making. We have much more work to harvest and disseminate lessons from our current cities on a variety of issues from blight reduction to chronic absenteeism, from building nonprofit capacity to addressing equity.

For organizations getting started with this work, we recommend finding champions in your community. Work with those stakeholders to demonstrate the value of applying neighborhood-level information to address a specific issue facing your community. Building up a comprehensive repository of data takes time; it is done incrementally. Look for low-hanging fruit: start with data that is most easily accessible and the most relevant for the issues facing your community. Reach out to NNIP and visit www.NeighborhoodIndicators.org to see how our partners might have tackled similar projects and issues. We are working on a guide that collects all of our advice on developing the NNIP model in new cities that will be released in 2016. People can keep up with NNIP through our public listserv and Twitter.

In conclusion, the NNIP presents a promising platform for promoting data-sharing ecosystems and the use of data-driven decision making at the neighborhood level. In our work looking at integrated service providers, including Washington Adventist Hospital and Briya-Mary’s Center, we have found that shortcomings in data collection, sharing, and usability hamper the use of integrated health and social service strategies. NNIP presents a promising platform for helping address some of these issues by helping local organizations, government, and foundations make better use of publicly available data, and by building the data-literacy of institutions and residents in poor neighborhoods. Also promising is NNIP’s initiative to establish and expand relationships between NNIP partners and Integrated Data Systems, to allow for the better use of data at the individual level.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Building neighborhood data to inform policy: A Q&A with Kathryn Pettit, director of the National Neighborhood Indicators Partnership (NNIP)

December 29, 2015