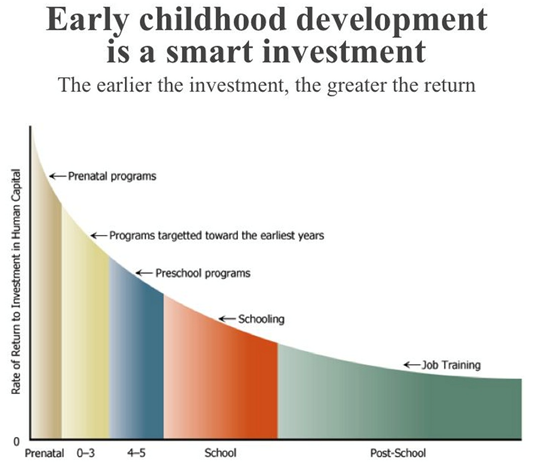

It is close to a cliché in social policy circles that “earlier is better”— but it is also largely true. While we should avoid the early years determinism of assuming that life chances are fixed by five, it is clear that it is typically more effective and more cost-effective to act early. James Heckman, the Nobel-prize winning economist from the University of Chicago, popularized the “earlier is better” movement with the curve below:

There has been a corresponding shift in recent years towards pre-K policies and parenting programs. But if Heckman’s basic premise is right, we should be paying even more attention to and investing even more dollars in pre-birth interventions.

The evidence on prenatal stress and child development

Stressful experiences for expectant mothers can have detrimental effects on their unborn children:

- “Prenatal insults,” such as harassment and discrimination, to pregnant Californian women with Arabic names after 9/11 resulted in higher rates of low birth weight babies, according to research by epidemiologist Diane Lauderdale. Babies who gestated in the weeks after 9/11 and who were given distinctive, Arabic names experienced a two-fold increase in underweight births compared to those who gestated before. Babies born to mothers with non-Arabic names experienced no such effect.

- Children in utero during a 40-day ice storm crisis in Québec had lower scores on tests of vocabulary and psychological measures at age 5.

- Using the timing of Ramadan as a natural experiment, economists Douglas Almond and Bhashkar Mazumder find persistent effects of prenatal fasting on disability outcomes as an adult.

The hypothesis: Fetal programming

Why? One strong possibility is that mothers send biological signals to their fetuses, providing information about the outside world and thereby helping prioritize different aspects of fetal development. Some scientists now believe this process actually alters which genes get “switched on” in newborns.

A particularly vivid illustration is provided by comparisons between the 1944 “Dutch Hunger Winter” and the siege of Leningrad, described by Laura Schulz in a 2010 article in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Mothers in both countries experienced food shortages while pregnant, which “programmed” the newborns for scarcity. But in adulthood, the children faced wildly different environments. The Dutch children grew up in an affluent society with easy access to food and they suffered from elevated rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease. The Soviet children, in contrast, experienced scarcity through adulthood, and their rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease were normal.

Prenatal environment can stunt development

The potential implications of this research extend beyond wars and famines, into every American home. Low-birth weight—an indicator of prenatal stress—consistently lowered academic achievement among Florida kids, even after controlling for family effects, demographics, and school quality, according to a study by economist David Figlio. Besides maternal stress, other prenatal environmental factors, like smoking and air pollution, can similarly inhibit child development. Clearly many of these factors are hard to alter. But we certainly need to try.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Born equal? Prenatal care and social mobility

February 24, 2015