The author directly draws portions of this blog from sections of the Human Development Report 2025, of which he served as the director and lead author.

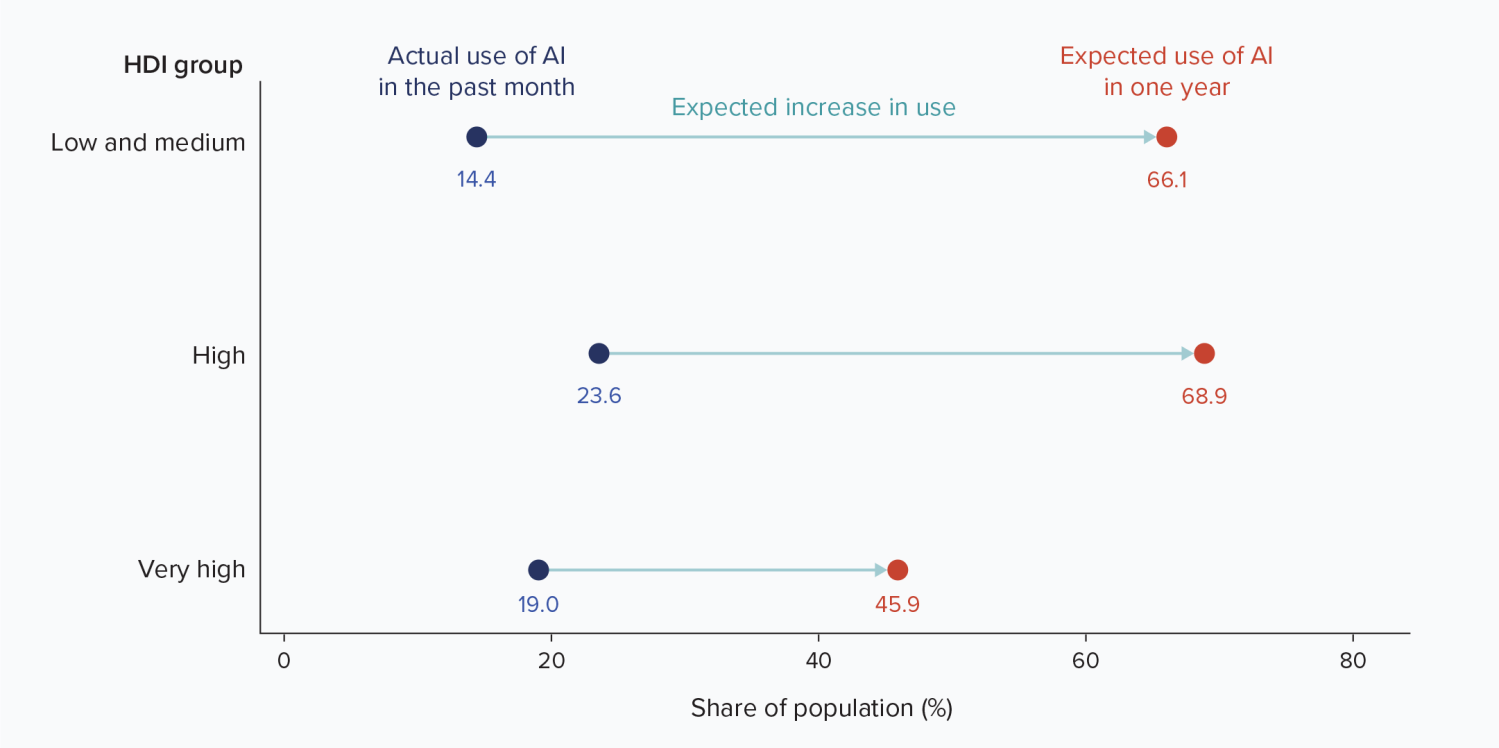

An original global survey conducted in preparation for the 2025 Human Development Report, which explored the potential of artificial intelligence (AI) to advance human development, found that around 20% of respondents around the world were using AI, at all Human Development Index (HDI) levels. But a more surprising finding was that about two-thirds of respondents in low, medium, and high HDI countries expect to use AI in education, health, and work—the three HDI dimensions—within one year, a much higher share than in very high HDI countries.

Source: Human Development Report Office based on data from the United Nations Development Programme Survey on AI and Human Development.

The 2025 Human Development Report argues that meeting this expectation is a matter of choice, countering techno-deterministic approaches that assume that AI will determine its future impact on humanity. A broader set of incentives and institutions will shape how AI’s use throughout the economy and across society can either improve or be detrimental to what matters to people. The urgent question for decisionmakers is not to predict what AI will do, but what kind of choices will leverage AI capabilities to enhance human development.

Meeting this expectation is also urgent, because the pathways that created jobs at scale and reduced poverty over the past two to three decades in lower income countries (based on expanding manufacturing industries and exporting to international markets) are narrowing. In part due to trade tensions that make prospects of exporting manufactured goods to higher income countries murkier, but also because of the automation bias of the ongoing digital transformations that is limiting job creation in manufacturing. In many lower income countries, the workforce is moving from agriculture to services, without a transition through manufacturing.

Thus, could AI offer new options to increase productivity in services? Would the price elasticity of demand of more productive services be sufficiently high to generate more jobs? Perhaps, if opportunities to leverage AI to complement or augment rather than replace work are explored. AI could also assist in the broader set of transformations historically associated with development (from rural to urban, from home production to market, from informal to formal, from self-employment to wage work) but also with the need to accelerate the transition to low-carbon economies. Seizing these opportunities requires more than understanding what AI can do as a technology. It calls for figuring out, given the structure of the economy, where AI investment could generate positive spillovers across sectors. Or how to deploy AI to scale up interventions proven to be effective to enhance learning and health outcomes. Or how to use AI to enhance public deliberation processes to advance collective action. All these themes are explored in detail in the 2025 Human Development Report.

Labor supply is abundant in lower income countries, but access to advanced expertise is constrained. AI can make advanced expertise more accessible, representing a new way for humans to take advantage of the knowledge others have accumulated over generations. It provides access to more than just information, extending to know-how, opening up new windows for people anywhere to solve problems and pursue ventures. AI can also potentially accelerate scientific inquiry and technological innovation by inspiring people to generate new ideas. These are some of the ways in which AI can be leveraged to meet expectations in lower income countries in ways that advance human development.

Along with recognizing the potential of AI, there is a need to avoid deploying what Daron Acemoğlu called “so-so” AI for things people already do very well. That would bring few if any productivity benefits, resulting in job losses and other downsides of AI, including exploitative labor practices in preparing data to be used to train AI models (like labeling images) and environmentally stressing energy and material requirements.

One important principle to leverage AI to advance human development is to go beyond focusing exclusively on the potential of AI for automation. By all means, deploy AI to automate tasks that are repetitive and a drudgery for humans, or where it can perform consistently better than people. But that is very different from seeing AI as something that can replace humans wholesale. Instead, AI’s potential is best leveraged to augment human strengths, such as intelligence and agency.

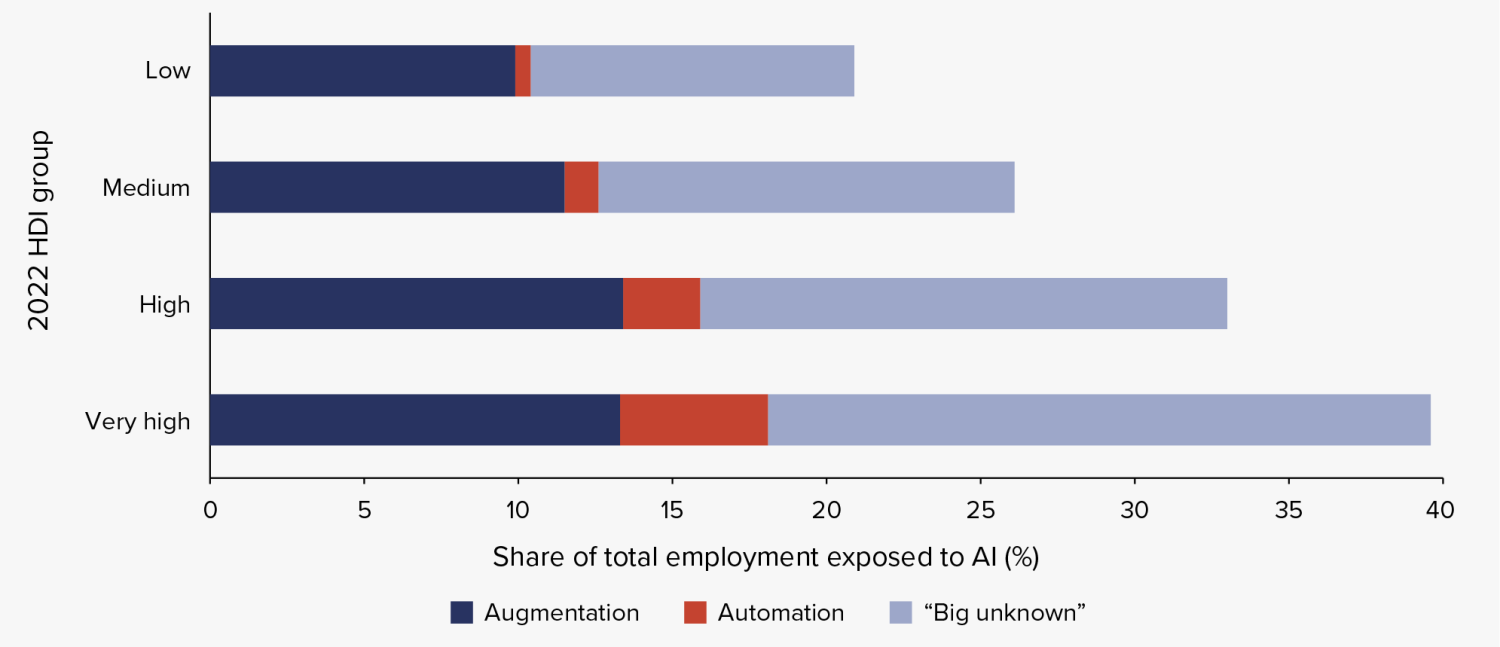

Automation and augmentation are twin features of the relationship between humans and AI that will determine AI’s impact on human development. In the world of work, the net effect on employment will depend on how the two forces balance out in the short term, on what new tasks are created on longer time scales, and on how demand for more efficiently produced goods and services will evolve—all uncertain but the result of deliberate policy, firm, and individual choices. Current estimates suggest that the largest share of jobs exposed to AI falls into “a big unknown,” with potential for both augmentation and automation across all levels of the HDI (see figure 2). Whether these roles will ultimately be augmented or automated is contingent on future AI progress and the choices made in response to those changes—presenting a major opportunity to shape the future of work in ways that could benefit workers and spur innovation and productivity.

Source: Human Development Report Office using data from the International Labour Organization Harmonized Microdata Repository and the method described in Gmyrek, P., Berg, J., and Bescond, D. 2023. “Generative AI and Jobs: A Global Analysis of Potential Effects on Job Quantity and Quality.” ILO Working Paper 96.

Beyond the “big unknown,” the share of current employment exposed to augmentation is of the same order of magnitude across all HDI groups (around 10%), but the share exposed to automation is an order of magnitude lower in low HDI countries. For every job exposed to automation in low HDI countries, there are 20 exposed to augmentation. In very high HDI countries, for each job exposed to automation, only 3 are exposed to augmentation. Seizing this opportunity for augmentation in low, medium, and high HDI countries is constrained by large gaps in infrastructure and basic capabilities. Bridging these gaps is one part of the task ahead to harness AI for development; the other is to enable people, firms, and governments in lower HDI countries to adjust and reorganize their activities to make the most out of AI.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Are we ready to meet the expectations of AI for development?

July 22, 2025