Sometime in the coming weeks Amazon will announce a short list of U.S. cities in which it will consider placing its new $5 billion, 50,000-person second headquarters. It is likely that these finalist cities will be large, prosperous, and located in the eastern part of the country.

Even in cities of a significant size and wealth, the arrival of what Amazon calls HQ2 will be transformative, even explosive. One only needs to look at the impact of HQ1 on Seattle to see why. Commentators in Seattle have taken to calling Amazon’s expansion the “prosperity bomb,” reflecting both the massive impact of the company’s growth and the heat of the ensuing fights about how that growth should be managed and distributed across the city.

With the prospect of a second “prosperity bomb” being dropped in a major American city, it’s not surprising that Amazon debates are raging. In fact, the Amazon HQ2 competition has focused the attention of a uniquely broad and diverse cadre of leaders across media, politics, business, and advocacy. Nationally, it has become a signpost for public policy issues ranging from antitrust to tax incentives to the need for policies that better support struggling communities. Locally, in each bidding city the response to HQ2 has simultaneously united a broad array of institutions around a shared economic development prize, and at the same time exposed fissures between elite-driven organizations and grassroots advocates about how bids should be executed, if at all.

Clearly, Amazon HQ2 has touched a nerve. So as we approach the one-year anniversary of the competition’s announcement, it’s worth stepping back and asking: how did we get here, and what should come next? To understand that, though, we first have to understand the unique rise of the world’s second largest company.

“Get Big Fast”

In 1994, Jeff Bezos founded Amazon in Seattle, after moving west from New York City. By one account, Bezos wanted to start the firm in the Pacific Northwest to tap into the region’s deep pool of engineers and its geographic proximity to a large book wholesaler in Oregon. Amazon’s original business was online book distribution. But as Brad Stone documents in his definitive Amazon account, The Everything Store, “Bezos wasn’t content to be a bookseller.”

A quarter century later, Amazon’s scope of activities has evolved to a staggering breadth of business lines, inspired by Amazon’s early motto of “Get Big Fast.” As Lina Khan of the Open Markets Institute writes, “in addition to being a retailer, [Amazon] is a marketing platform, a delivery and logistics network, a payment service, a credit lender, an auction house, a major book publisher, a producer of television and films, a fashion designer, a hardware manufacturer, and a leading provider of cloud server space and computing power.” With its purchase of Whole Foods in 2017, Amazon is now a grocer as well.

This breadth of commercial activities arises from Amazon’s distinct obsession with scale, and its calculation that tremendous bottom-line benefits will accrue to a new breed of tech-enabled mega-firms that serve as online platforms. Platforms differ from traditional large companies in that they not only provide goods and services to consumers, but also provide the architecture on which other businesses conduct their business. In this way, the more users—whether a customer or a business—that engage with Amazon, the greater the benefit to those users. Economists call these network effects, and Amazon has exploited them to acquire massive reams of data to optimize its operations and power its growth.

In this way, Amazon is both a partner and competitor to much of the marketplace. This powerful position has raised significant concerns about whether Amazon’s ascendance has been enabled by anticompetitive practices.

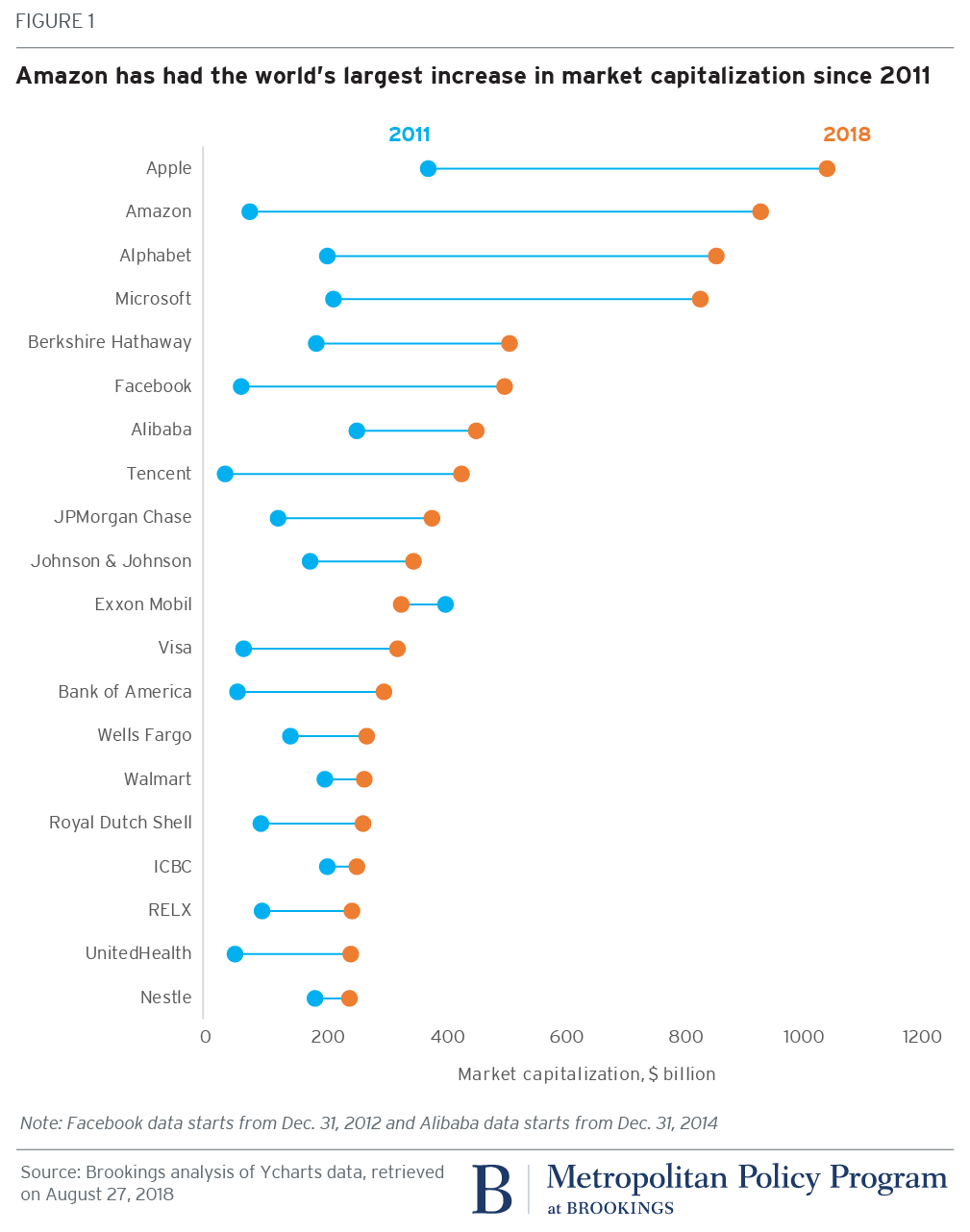

Whether an example of monopoly power or a cunning mastery of the technological complexity and global scale of the modern economy (or both), Amazon’s growth has been astounding. In 2015, the firm was not among the world’s ten largest in terms of market capitalization. By June 2018, Amazon’s market capitalization reached $825 billion, propelling it past Alphabet to become the second largest company in the world behind Apple. Its employment rolls have expanded from 33,700 in 2010 to 575,000 in 2018.

Amazon drops the “bomb” on Seattle

About 45,000 of these employees are based in Seattle, by far the largest and most handsomely compensated concentration of workers in Amazon’s global footprint. With such a large presence, Amazon’s physical imprint on the city is impossible to miss, especially in and around its headquarters in South Lake Union. Amazon now occupies 33 buildings in Seattle, a total soon to grow to 40. By comparison, the federal government operates 55 buildings in the District of Columbia.

Amazon estimates it has generated $38 billion in economic activity in Seattle between 2010 and 2016. Partly as a result, the city of Seattle and the broader region are booming. My Brookings colleagues found that on a set of indicators measuring changes in regional prosperity, the Seattle region ranked third in the nation between 2006 and 2016. Even as national unemployment is nearing all-time lows, Seattle’s is even lower.

Amazon now occupies 33 buildings in Seattle, a total soon to grow to 40. By comparison, the federal government operates 55 buildings in the District of Columbia.

Being highly skilled in Seattle—as in many cities—brings a tremendous quality of life. All of this growth has brought new restaurants, entertainment, and enjoyable outdoor spaces. But even if you aren’t a programmer at Amazon, you may benefit as well. That is because tech jobs create spillovers in the broader economy, since highly paid tech workers create more demand for dry cleaners, doctors, and dining out. Indeed, economists have found that the presence of high-tech jobs has modest positive wage benefits for workers in locally-serving industries. In Seattle, it seems those gains are real. While not directly attributable to Amazon, previous Brookings research found that families with incomes at the 20th percentile of the earnings distribution grew their incomes by 14 percent between 2014 and 2016, placing Seattle in the top-third of large cities over that period.

So if both creative class and working class incomes are increasing, why is there considerable angst among lower and working-class families in Seattle? That dynamic arises from the fact that income growth has not been robust enough to compensate for the city’s declining affordability. During this same 2014 to 2016 period, rents increased by 19 percent, according to Zillow. Indeed, economists have also shown that the spillover wage gains from high-tech growth only tend to accrue to locally-serving workers that live in cities that built lots of new housing simultaneous to the expanding tech industry. When housing supply was constrained, as has occurred in Seattle, the cost of living increases experienced by the working class outstripped any wage gains.

While Seattle developers are building housing, demand has well exceeded supply. The ensuing tensions associated with Amazon and the city’s declining affordability have been palpable. As Victor Luckerson reported, “the HQ2 search was an acknowledgement that Amazon was getting too big for Seattle. It also hinted that Seattle might be getting too unpleasant for Amazon.” This perceived hostility, Luckerson said, led “five City Council members to sign a letter to Bezos apologizing if the company felt “unwelcome” in the Puget Sound, an olive branch meant to keep HQ2 in Washington.”

But activists and the far-left flank of the city council remain much more skeptical about the value of Amazon to Seattle. Most defiantly, City Council member Kshama Sawant, following the City Council’s failure to enact a new tax on large employers over the objections of Amazon and the Seattle business community, exclaimed that “Jeff Bezos is our enemy.”

City shopping, Amazon-style

In Seattle, the Amazon prosperity bomb has generated, well, prosperity. But the tensions in Seattle reflect Amazon’s growing pains as well.

Against this backdrop, one year ago Amazon announced a request for proposals (RFP) to host a second corporate headquarters. While the civic tensions in Seattle likely played a role, this decision is likely much more about the company’s outrageously ambitious hiring plans and the fact that few, if any, cities can handle that level of scale-up. Amazon simply outgrew its backyard.

In a uniquely public competition, the company asked cities to highlight several local assets: the education and skills of their workforce, the quality of their transit and built environment, the strength of their schools and universities, and the livability of their communities. Amazon also requested each jurisdiction to describe what level of tax incentives they would provide so that the company could understand how tax breaks would help defray the initial cost of its proposed $5 billion investment.

The criticism of the competition has been swift and harsh. Economists derided both the inefficiency and unfairness of using local and state taxpayer money to subsidize a business decision that Amazon, by its own acknowledgement, needed to make. Good Jobs First, the leading advocate against corporate subsidies, condemned the competition as a “monument to high-tech arrogance and tax-break favoritism.” CityLab’s Sarah Holder penned an article titled, “Council Members, Kochs, and Socialists Unite Against Amazon.” Indeed, the HQ2 competition has created a unique coalition of the offended.

Amid this skepticism, economic development organizations and elected officials jumped at the chance to land Amazon. In response to the request, Amazon received 238 proposals from North American cities aiming to become the site for HQ2, including many offering generous incentive packages.

That shouldn’t be a surprise. Since capital has been mobile, U.S. cities and states have competed for it through tax incentives. Today, local and state governments spend between $45 and $80 billion on incentives, depending on the estimate. The HQ2 competition has taken these sums to new levels, with local and state governments in Maryland and New Jersey each offering incentive packages exceeding $7 billion.

The fact that states and localities use tax policy to shape private sector behavior is quite reasonable. But at a certain point large incentive packages such as these are zero-sum and even self-defeating, as weakened government coffers cannot support the high-quality public goods that firms like Amazon demand in the first place.

Today, local and state governments spend between $45 and $80 billion on incentives, depending on the estimate. The HQ2 competition has taken these sums to new levels.

Many speculated that Amazon would end up choosing an already wealthy, innovation-rich and high-functioning region in North America’s eastern half. In January, Amazon narrowed the list from 238 proposals to 20, all housed in relatively large and well-educated metropolitan areas. There were few, if any, surprises, adding to the skepticism that Amazon knows where it wants to place this investment and is simply extracting maximum value from the winner through a public auction.

So if Amazon knows where it wants to go—and could extract maximum incentive value by quietly pitting a few cities against each other—why undertake this public competition at all? There are several elements to the unique HQ2 process that reflect Amazon’s broader corporate ethos and strategy.

One potential reason is Amazon’s obsession with data to inform major corporate decisions. In a 2015 shareholder letter, Bezos labeled these Type 1 decisions. Type 1 decisions, Bezos wrote, “are consequential and irreversible or nearly irreversible—one-way doors—and these decisions must be made methodically, carefully, slowly, with great deliberation and consultation. If you walk through and don’t like what you see on the other side, you can’t get back to where you were before.”

Amazon HQ2 is a Type 1 decision, and thus likely required a deliberate approach. The 238 proposals resulted in a massive trove of relevant data and intelligence that now constitutes the most comprehensive database of local market and civic intelligence in the world. While Amazon’s well-staffed site selection team probably could have crunched the numbers and conducted site visits to arrive at its HQ2 shortlist without the public solicitation, even it would have trouble tracking down every recent or planned civic initiative which may influence the company’s choice for HQ2.

Moreover, this database will inform future investments in North America. Even as Amazon has committed to plopping $5 billion in one place for HQ2, it is also building logistics facilities, R&D hubs, data centers, and back offices in communities across the continent. In April alone, the company announced it would add 3,000 jobs in Vancouver and 2,000 jobs in Boston. Just as it uses big data on shopping behavior to algorithmically match people to products, Amazon now has the data and intelligence to optimally match investments to places.

Just as it uses big data on shopping behavior to algorithmically match people to products, Amazon now has the data and intelligence to optimally match investments to places.

This leads to the second way in which the competition reflected Amazonian strategy: the absurdly quick turnaround to respond to the RFP served as a decisive civic “stress test” for local communities. Amazon is renowned for pushing its employees to the absolute brink of their abilities to arrive at the best decision possible. A New York Times profile described Amazon as a corporate culture “willing to embrace risk and strengthen ideas by stress test.”

By all accounts, the tight, six-week deadline served a similar purpose. By pushing cities to the brink, Amazon could test which places could activate their institutional networks to respond with speed and comprehensiveness, drawing in the expertise and resources of economic development groups, workforce boards, mayor’s and governor’s offices, universities, community groups, and local businesses. More cynically, the quick turnaround has limited the time and space for public reflection and vetting of the bid. Public transparency has been severely lacking in the process, and the 20 shortlisted cities have all signed non-disclosure agreements.

Public transparency has been severely lacking in the process, and the 20 shortlisted cities have all signed non-disclosure agreements.

Even simple things, like the organization that submitted the bid or the number of bids per region, provided signals as to the civic and political dynamics that Amazon may one day confront in their adopted home. For instance, Greater Toronto submitted a bid representing the entire regional economy, with sites in the City of Toronto and outside. By contrast, the District of Columbia, the Maryland suburb of Montgomery County, and Northern Virginia each submitted separate applications, revealing the competitive dynamics between these different jurisdictions.

Who benefits from Amazon’s arrival?

Outside of a few communities that have made their applications publicly transparent, the Amazon HQ2 proposal has generated more heat than light. The intensity of the debate draws not only from the lack of transparency, but from the breadth of societal questions that the HQ2 competition has brought to the public’s attention.

The most prominent and contentious question being discussed in the shortlisted cities: Will Amazon’s arrival actually benefit local residents, particularly lower income and working class residents, or simply exacerbate existing structural inequities within metropolitan America?

Will Amazon’s arrival actually benefit local residents or simply exacerbate existing structural inequities within metropolitan America?

Currently, it’s unclear exactly what HQ2 will offer in terms of labor market opportunities, but it will likely concentrate in occupations that require higher levels of education. According to Paysa, about 80 percent of Amazon employees have at least a Bachelor’s degree. For advocacy groups focused on equitable development, there is a deep skepticism that the massive infusion of wealth and prosperity accompanying HQ2 will help ameliorate existing inequities.

Two reasons animate this skepticism. First, due to its education requirements, there is a fear that Amazon will mostly hire people from outside the local labor market. In this scenario, the upside accrues to highly-skilled entrants while existing residents must now deal with the knock-on costs in the form of higher housing prices and added congestion.

Second, if public incentives are provided—and those incentives are paid for by weakening investment in public goods on which lower income people disproportionately rely—than there could be an additionally regressive impact on the community. That so many mayors, governors, and economic development organizations have refused to release the amount of incentives being offered to Amazon has heightened these fears and sowed further distrust between activists and those running the bid. As Nikil Saval has posited, there may be a deeper backlash accruing in the bidding cities “where left-wing organizations birthed out of [the 2016 campaign], alongside those long in existence, are moving to take power from the city machines, old and new.”

This skepticism is completely warranted and, in fact, necessary to hold leaders to account in this major public policy decision. But proponents in the shortlisted cities have a case to make as well. As offensive as the public subsidy aspect of the economic development system remains, even the most dynamic regional economies could benefit from 50,000 jobs. An Amazon headquarters would be especially transformational for the smaller, Heartland metro areas left in the competition which are not yet suffering from the affordability crises on the coasts. From a distributional perspective, Amazon will not be hiring 50,000 Ph.Ds., and the firm could follow Google and Apple by ditching college degree requirements to make its hiring fully based on demonstrated skills, not pedigree. The potential upside is likely too great for elected officials, who are under intense pressure to deliver for their communities, to ignore.

The question is not whether to receive major corporate investments such as these—cities don’t really have a choice in the matter—but how?

Four pillars for a “grand bargain”

In one scenario, absent any semblance of intentionality, Amazon could drop another unplanned prosperity bomb, a regressive explosion that heightens inequality, spurs gentrification, and diminishes social cohesion. In another scenario, Amazon HQ2 could serve as more of a controlled power source, one that economically energizes as many people and communities as possible.

Admittedly, there is not a clear roadmap for channeling an investment of this scale, and it is entirely possible that it is beyond the abilities of any city to do so. But if it were tried, it could result in a new type of private-public-civic partnership, one that draws on an enlightened self-interest to invest in people, businesses, and infrastructure that together drive shared prosperity.

How could such a “grand bargain” unfold as Amazon enters into a final round of negotiations with the finalist cities? Here are four core pillars for local leaders and the company to consider:

One: Catalyze a cluster of high-growth firms and locally-serving businesses around Amazon.

Like many large firms, Amazon benefits from being located within industry clusters—groups of firms that gain a competitive advantage through local proximity and independence. By being a part of dense, knowledge-rich environments, Amazon can better facilitate knowledge exchange with smaller companies, especially if the receiving city already has a significant specialization in one of Amazon’s core functions. One example of Amazon drawing on the clustering phenomenon is the firm’s investment in the Seattle-based Alexa Accelerator, a partnership with Techstars that helps startups incorporate Amazon’s popular Alexa artificial intelligence platform into their businesses. Securing Amazon’s investment in a new accelerator, or its support of an existing one, increases the chances that the winning city can seed the next Amazon.

Amazon’s massive footprint will also create opportunities for locally-serving businesses doing everything from food preparation to event planning to legal services. The winning city should advocate that Amazon consider local suppliers when making procurement and vendor decisions for its activities at HQ2.

Two: Prepare current residents for employment opportunities generated by Amazon’s arrival.

One of Amazon’s biggest challenges is finding the necessary talent to support its growth. It therefore has a strong motivation to increase the skills and competencies of the current and future workforce in its backyard. Its desire to “hire and develop the best” has led to the creation of its Career Choice program, through which 10,000 employees have worked towards a certificate or diploma that prepares them for an in-demand career (either within or outside the company). Amazon has also shown willingness to offer work-based learning opportunities such as apprenticeships to develop its next generation of workers, invest in coding programs and STEM education, and support the computer science department at the University of Washington.

While many jobs will be filled by qualified workers moving into the region, Amazon should partner with local education, workforce development, and economic development entities to prepare as many current residents as possible to work at HQ2. This should start with short-run training programs in key skills, such as what Amazon has done with its technical apprenticeship program.

While many jobs will be filled by qualified workers moving into the region, Amazon should partner with local education, workforce development, and economic development entities to prepare as many current residents as possible to work at HQ2.

Longer term, Amazon should also co-invest with public and educational institutions to educate and train its workforce of the future. This could involve partnerships with local school districts to expose children to STEM education, mentorship programs between Amazon employees and local youth, and career exposure days at the HQ2 campus. It could extend to formal offerings of work-based learning opportunities for young people, such as internships, externships, and apprenticeships. Partnerships with universities and community colleges can help expand resources, as occurred at the University Washington, and sharpen the real-world relevance of academic curricula. The District of Columbia, for instance, has offered to create an Amazon University that would provide customized training for individuals seeking employment at the company. These need not necessarily be Amazon-specific partnerships, however. Amazon will likely generate churn in the local labor market by hiring away from existing employers, creating openings in related occupations through the regional economy. Much of the architecture for these types of employer-educator partnerships already exists, but Amazon’s resource base and talent requirements offer an opportunity for immense scale in these offerings.

Three: Support housing supply to ameliorate growing pains.

Even with the most ambitious workforce development effort imaginable, many local residents will not be directly employed by Amazon. For anyone not directly benefiting from Amazon HQ2, there are well-founded concerns that their cost of living will increase as new arrivals bid up the price of housing. As such, local officials need a plan to increase the region’s housing supply by zoning for new market-rate housing development. Yet, even with expanded market-rate housing development, there will still be affordability challenges. A portion of the tax revenue generated by Amazon’s arrival needs to be explicitly set aside for a fund to preserve and expand affordable housing. Of course, the size of this investment fund depends on the ability to actually secure tax revenue from Amazon, which will be determined by the size of the incentive package provided.

Four: Prepare for the future, but don’t forget the past.

People like talking about HQ2 because it’s forward-looking and hopeful. The prospect of securing Amazon has generated lots of optimism among people and communities that have historically benefited from similar corporate investments. But in each of the remaining cities, systemic inequities along race and class decades in the making have created an uneven opportunity structure that selectively disadvantages many other groups. And among those communities, there is rightly skepticism that an Amazon investment will work for them.

The cities preparing for HQ2 would do well then to heed the advice of my colleague, Amy Liu, who argued in a CityLab piece that for the nation to achieve shared prosperity, “cities will need to simultaneously make right the wrongs of the past while radically preparing for the future.”

That means that as local leaders facilitate business development in the wake of Amazon’s arrival, they need to engage a wide set of entrepreneurs, business intermediaries and community development groups that reflect the diversity of the entire region.

As Amazon contemplates educational partnerships, it should look not only to the major research university, but also tap the student bodies of HBCUs and community colleges.

And as the city considers zoning changes and development schemes, it must consider the interests of low-income and minority communities, in addition to those of wealthier homeowners who may be able to exert more political pressure.

As Amazon contemplates educational partnerships, it should look not only to the major research university, but also tap the student bodies of HBCUs and community colleges.

Many will argue that this is morally the right thing for corporations to do, and I would agree. But Amazon has a bottom-line rationale as well. By being oblivious about existing economic and racial inequities in its own backyard, Amazon risks fomenting the same societal tensions that it is leaving behind in Seattle.

Amazon’s growth and planned headquarters expansion is not simply a memorable economic development story; it uniquely epitomizes the trends roiling our economy and society. In this era, large, technology-enabled companies can draw up on a breadth of markets and revenue streams that supercharge their growth beyond any one city. The power those companies wield is only amplified by the incentive-laden job creation systems our cities and states have established, a system in which each is competing in a non-transparent market to woo the next large prospective employer. Ironically, Amazon’s uniquely public competition has shone much-needed light on this suboptimal economic policy approach.

Yet, individual jurisdictions and elected officials—in the case of HQ2, at least—cannot, and probably should not, turn away from such a potentially transformative investment. Any public policy decision involves choices, and it will be up to the leadership of the remaining cities to maximize the benefits of Amazon’s arrival while minimizing the costs. Most commentators remain skeptical the remaining cities will be able to execute such a bargain. But if done right, one city could attract a transformative company while investing in shared regional assets that benefit Amazon but also workers, communities, and other businesses.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).