One year after a Tunisian fruit vendor set himself on fire in an act of defiance that would ignite protests and unseat long-standing dictatorships, a harsh chill is settling over the Arab world. The peaceful demonstrations in Bahrain, Egypt, Libya, Syria and Yemen that were supposed to bring democracy have instead given way to bloodshed and chaos, with the forces of tyranny trying to turn back the clock.

It is too soon to say that the Arab Spring is gone, never to resurface. But the Arab Winter has clearly arrived.

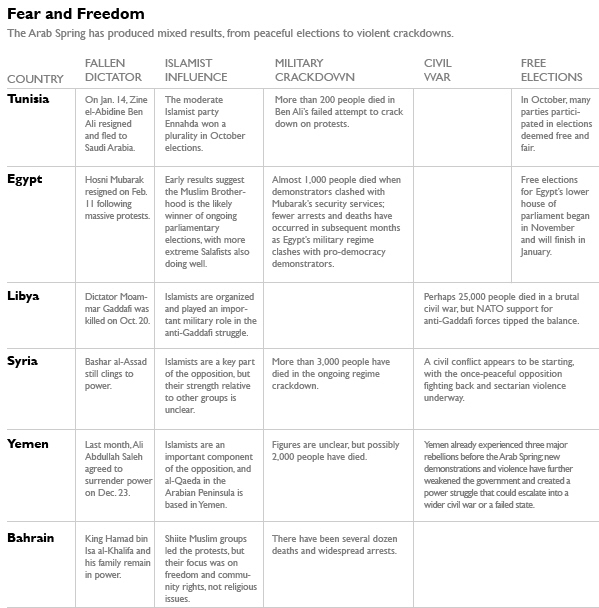

Tunisia, where it all began, recently carried out free elections. But that country — small, ethnically and religiously homogenous, and prosperous — was always a more likely candidate for a successful transition to democracy. Elsewhere in the Middle East, Saudi troops helped orchestrate a crackdown on demonstrators in Bahrain, regime forces gun down protesters in Syria, and Yemen crumbles into civil war, with al-Qaeda running rampant in the countryside. In Libya, we see warlords, Islamists, tribal leaders and would-be democrats vying for power in the post-Gaddafi world. And in Egypt, where the fall of President Hosni Mubarak in February gave us the defining images of the Arab Spring, the military is trying to keep its hands on power.

So what went wrong — and what will an Arab Winter mean for the Middle East, the United States and the rest of the world?

The reason the Middle East has long seemed like infertile soil for democracy is not because Arab peoples do not want to vote or otherwise be free — poll after poll confirms the opposite — but rather because entrenched dictators had long imprisoned or killed dissenters, bought off opponents, undermined civil society, and divided or intimidated their people. And when dictators fall, their means of preserving power do not always fall with them.

In Egypt, the military ushered Mubarak out of office, but stayed in as a supposed caretaker and is reluctant to relinquish power. Now the security forces have again shot people in Tahrir Square. In Yemen and Libya, tribes and other power centers often opposed the old order, but they saw one another as rivals, too. Throughout the region, the police and the judiciary are broken after years of dictatorship, but there is nothing to take their place.

Moreover, the demonstrations that led to the ouster of rulers such as Mubarak and Tunisia’s Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali hardly offered a clear governing alternative. Although they embodied a genuine outpouring of popular rage, the protests were largely leaderless and loosely organized, often via social media; there was no African National Congress or Corazon Aquino to take the reins. You cannot govern by flash mob.

And the opposition voices that were organized were not necessarily the most democratic. With the Arab Spring, Islamist forces rose to prominence. In Tunisia, a moderate Islamist party won victory in the October elections, gaining 89 of 217 seats in parliament, dwarfing the 29 seats of its nearest — secular — competitor. In Morocco, where the king has opened the political system somewhat, the Islamist party likewise won a plurality of the vote in the November elections.

Disciplined by years underground, Islamist groups have popular support because of the social services they provide and the repression they suffered. They were allowed to have a role in society but with limited political participation. Now that groups such as Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood are poised to do well in free parliamentary elections, they are unlikely to accept those old bargains with the military junta in Egypt or other old-regime forces elsewhere.

Brotherhood leaders have learned to mouth a commitment to pluralism and tolerance, but it is unclear that they would act on it when in power. More hard-line Islamists are openly skeptical of democracy, seeing it as a means of gaining power and not as a model for governing. Egyptian salafists, who espouse a more puritanical version of Islam, have also entered the political system and are performing unexpectedly well in the elections; their demands for Islamicizing society are extreme and may push the Brotherhood to pursue a more radical agenda when in power.

These domestic forces often deter democracy in subtle ways, but some other reactionary forces are more brazen. In March, Saudi troops drove across the causeway to neighboring Bahrain, backing a brutal crackdown against Shiite protesters. At home and abroad, the Saudis have spent tens of billions to buy off dissent. Riyadh has pushed fellow monarchs in the Arabian Peninsula and in Jordan to stop any revolutionary movements, and the Saudis are offering a haven for dictators down on their luck, such as Tunisia’s Ben Ali.

The Saudi royals not only worry about their own power diminishing, but fear that change elsewhere would be an opening for their arch-rival Iran and for al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula. As Middle East expert Bruce Riedel puts it, the Saudis have proclaimed a 21st-century version of the Soviet-era Brezhnev doctrine: “No revolution will be tolerated in a bordering kingdom.”

A faltering Arab Spring doesn’t mean we will return to a world of dictators and secret police. Not only are Mubarak, Ben Ali and Moammar Gaddafi gone, but so are the cults of personality they nurtured. Bashar al-Assad may cling to power in Syria, but he will be isolated abroad and hollow at home. Even regimes that have experienced limited unrest — Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Algeria — are entering a new era.

Where old regimes survive, they will be weak; where new ones come in, they will be weaker, because old institutions can be destroyed more quickly than new ones can be built. Both new and old leaders must play to public opinion, and this may lead to rash, incoherent foreign policies, as politicians make campaign promises that are not in their countries’ interests to fulfill.

Israel, of course, is the easiest card to play. A Pew Research Center poll taken after Mubarak’s fall found that Egyptians favored annulling the 32-year-old peace treaty with Israel by 54 percent to 36 percent, and — no surprise — many mainstream leaders have criticized it. Indeed, Israel can serve as a perfect diversion to struggling governments. In May, as unrest swept across Syria, the regime encouraged Palestinians to march across the Syrian border into the Golan Heights, leading to four deaths when an Israeli border patrol shot Palestinians as they broke through a frontier fence.

Even if violence involving Israel does not escalate, a renewed push for peace seems unlikely. “The ugly facts,” wrote former Israeli defense minister Moshe Arens, “are that the two peace treaties that Israel concluded so far — the one with Egypt and the other with Jordan — were both signed with dictators: Anwar Sadat and King Hussein.” It is hard to imagine new leaders, who need to play to anti-Israel public opinion, sitting down with their Israeli counterparts to advance peace.

Anti-Americanism is also likely to rise in the Arab Winter — and it matters much more now that governments will seek to be in tune with public sentiment. After Mubarak’s fall, for example, only one in five Egyptians had a favorable view of the United States (just slightly higher than under Mubarak), and even in Mideast nations that are allied with Washington, majorities identify the United States and Israel among the top two threats to their security.

One of the ironies of U.S. support for democratic change is that the autocrats have traditionally been more pro-American than the democrats. Now, forces of the old regimes feel that Washington abandoned them at their most vulnerable time, and Jordan and Saudi Arabia are livid that the United States abruptly dumped Mubarak and question the U.S. commitment to their security.

The United States may end up with the worst of both worlds: scorned by the forces of democracy because of its ties to dictators, but disdained by dictators — whose cooperation is vital to U.S. economic and security interests — for reaching out to democrats.

The most dangerous outcome of the Arab Winter, however, is the spread of chaos and violence. In Syria, where thousands have already died, the body count may grow exponentially as sectarian killings spread and peaceful protesters take up arms. In Yemen, the resignation of Ali Abdullah Saleh has not ended the turmoil throughout the country. And Libya, lacking strong institutions and divided by tribal and political factions, may never get its new government off the ground.

If unrest spreads, families will leave their homes, burdening neighboring states and incubating fighters for future conflicts. Perhaps 1 million Libyans sought refuge in nearby countries while civil war raged there this year. Tens of thousands of Syrians have fled, and more will leave if the violence there escalates — as it shows every sign of doing. In Turkey, Syrian refugees could become a source of recruits for a future opposition army that would fight the regime in Damascus.

These conflicts could widen if neighbors intervene, whether because they fear more instability or because they want to consolidate their influence across borders. Saudi Arabia has long meddled in Yemen, for example, and the collapse of that regime may lead the Saudis to move directly against al-Qaeda forces and other perceived threats there. Meanwhile, Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Jordan and Israel all have strong interests in Syria and may arm factions or otherwise get involved simply to offset their rivals. Neighboring Lebanon’s history of civil war and foreign intervention offers a depressing precedent for how a local conflict can drag in neighbors.

Distrusted and broke, the United States can do little to make the Arab Winter better, but it can do a lot to make it worse. The value and possibility of economic aid, for instance, are questionable. Regimes such as Mubarak’s used American aid to prop themselves up and resist democracy. While supporting new democratic parties is a better use of dollars, it is hard to imagine a budget-conscious Congress approving serious aid for new governments that will inevitably include anti-American Islamist groups with a questionable commitment to democracy. Nor would the region’s true democrats necessarily welcome U.S. support, with its stench of foreign interference.

Washington has the most influence with the region’s militaries, but supporting them presents a dilemma. Militaries were supposed to be the “orderly” part of an orderly transition to democracy in the Middle East, but as Egypt’s experience makes clear, most officers want to keep their perks and power, and U.S. support can help them do that. Outside Egypt, militaries are politicized by tribe (Yemen), sect (Syria) and loyalty to the old order (everywhere), making them part of the problem, not the solution.

The Arab Spring began without U.S. help, and the people of the region will be the ones to determine its future. Washington should recognize that change is coming and support it, especially in key power centers such as Egypt. But inevitably it will play catch-up, managing crises where it can or must to keep instability from spreading. This could involve helping refugees, using diplomacy to try to prevent neighbors from intervening and escalating a conflict, and continuing to aggressively pursue al-Qaeda affiliates so they do not threaten Arab nations or the United States.

Just a few months ago, President Obama optimistically declared that, across the Arab world, “those rights that we take for granted are being claimed with joy by those who are prying loose the grip of an iron fist.”

We can hope that Tunisia will lead the region not only in loosening that grip, but in creating real democracy through free elections. However, we must also recognize that the Arab Spring may not bring freedom to much, or even most, of the Arab world. Even as the United States prepares to work with the region’s new democracies, it also must prepare for the chaos, stagnation and misrule that will mark the Arab Winter.

It is too soon to say that the Arab Spring is gone, never to resurface. But the Arab Winter has clearly arrived.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edAfter the Hope of the Arab Spring, the Chill of an Arab Winter

December 4, 2011