Content from the Brookings Institution India Center is now archived. After seven years of an impactful partnership, as of September 11, 2020, Brookings India is now the Centre for Social and Economic Progress, an independent public policy institution based in India.

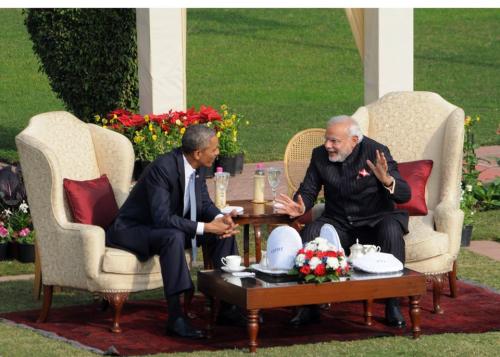

The first surprise came when President Barack Obama telephoned Narendra Modi on May 19, 2014 before he was sworn is as India’s 15th prime minister. Fevered speculation in New Delhi and Washington about whether and when the United States would come to terms with India’s new prime minister stopped abruptly. Not only did they talk, but Modi promptly accepted Obama’s invitation to visit the White House. The good relationship they established blossomed further with Modi’s invitation to Obama to attend the Republic Day festivities, an important first.

By the time the Indian election results were announced last May, Washington observers generally welcomed a Modi government, believing it would revive the Indian economy, whose success over 25 years had fueled a transformation of U.S.-India relations. They also hoped a business-oriented government would resolve some of the commercial issues that had contributed to a slump in India-U.S. ties.

Hence the next surprise: Modi’s foreign policy made a bigger splash than his economic stewardship. His high-octane travel to the world’s most powerful countries and especially his creative and energetic economic outreach to India’s smaller South Asian neighbors showed boldness and imagination that few expected from a leader with little background in foreign affairs (despite his overseas trips when he was chief minister of Gujarat).

Modi did indeed focus on the Indian economy. The change in leadership in New Delhi, with some help from the business cycle, helped produce increased growth and the expanded investment that followed. The two budgets presented during his first year had some useful initiatives but few economic game-changers.

But the third and biggest surprise for those bullish on India is that Washington and New Delhi have different notions of what “boosting the Indian economy” means in practical terms. Modi’s signature economic initiatives are projects: “Smart cities” embody the dream of India’s economy surging to an electronically powered boom. “Make in India” captures the vision of a resurgent Indian manufacturing sector, propelled more by capacity building and incentives than by fresh import restrictions. Infrastructure is very concrete – and creates things made of concrete, capable of being photographed.

The United States has bought into some of these projects. In particular, U.S. businesses are working on three of the “smart cities.” But Washington tends to focus more on policies: fiscal and monetary policy, tax transparency, investment rules it would like to embed in a treaty, the functioning of the World Trade Organization (WTO), and many more. In the United States, these policies create the rules that permit private business to invest and create jobs, and enable international commerce to grow.

Two recent problems between the United States and India illustrate the different perspectives. The first is India’s decision in July 2014 to block WTO approval of a measure the previous government had accepted, which combined agreement on steps to remove administrative bottlenecks from trade (the Trade Facilitation Agreement, or TFA) with a compromise solution to a disagreement over the maintenance of agricultural stockpiles. The Modi government said “no,” seeking to use the leverage of TFA to improve the agriculture deal.

The Obama administration was stunned at this reversal of India’s position on an agreement where, as they saw it, India had achieved most of its objectives – an agreement whose failure would (again in Washington’s view) threaten the viability of the international trade system. The Modi government was equally stunned that its action caused such anger in Washington. India did not understand the importance the U.S. government attaches to keeping the WTO functioning as a forum for negotiating multilateral agreements and resolving disputes.

Four months after the Indian “no” came a mutual “yes” from the two leaders – on terms little changed from the original agreement. This left the U.S. relieved, but also wondering why India took what looked, in the U.S. view, such great risks on an issue where the final result was little changed from the one it objected to.

The second example is one that directly affects U.S. businesses in India: the unpredictability of the Indian tax system, and especially the use of retroactive taxation. The best illustration of unpredictability was the sudden, or so it seemed from Washington, decision of the Indian tax authorities to begin levying the alternative minimum tax against portfolio investors. For years, that tax had not been applied to overseas-based financial investors; suddenly, without any change in the law, companies not based in India were being hit with multi-million dollar tax assessments. As for retroactive taxation, the U.S. constitution’s prohibition on ex post facto laws added to the shock when such practices crop up in India, as in the Vodafone case. Both seemed like obvious candidates for a reform-minded prime minister to change India’s regulatory and tax system.

One could blame these misunderstandings on unfamiliarity with foreign countries’ practices, and let it go with a shrug – except for one thing: this kind of misunderstanding has heavy consequences in the real world. India is far more integrated into the global economy than it was 25 years ago, when its economic transformation began. Trade now accounts for over half the Indian economy, compared with 15 percent in 1990. India has benefited from international investment, and wants more. Private commercial dealings have been an engine of the U.S.-India relationship, to the great benefit of both sides. And it is not just U.S. businesses that will be turned off by India’s regulatory unpredictability or by the perception that India is prepared to block the working of the global trade system.

A year after Modi took office, he and Obama deserve credit for an exciting re-launch of U.S.-India relations, energized by their countries’ shared interests, especially in Asia. They can take satisfaction in Modi’s focus on the economic dimension of foreign policy. In the next year, they need to tackle the areas where their economic perceptions are badly aligned. They need to focus on project implementation, on making the international system run more smoothly, and on regulatory predictability.

Download the Complete Briefing Book

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edA Washington Perspective: Three Modi Surprises

IndiaGov@365

May 25, 2015