“Nothing is so boring to the layman as a litany of complaints over the more obscure provisions of House procedures. It is all “inside baseball”….We Republicans are all too aware that when we laboriously compile data to demonstrate the abuse of legislative power by the Democrats, we are met by reporters and the public with that familiar symptom best summarized in the acronym “MEGO” — my eyes glaze over.”

So bemoaned then Minority Leader Bob Michel in this Letter to the Editor of the Washington Post in 1987. Well, the ballgame’s gone outside. Just when you thought reporters had tired of refereeing reconciliation, the Byrd Rule, and filibusters, everyone’s trekked over to the House ballfield for a game with self-executing rules.

Here, I offer a brief perspective on the use of self-executing rules, given the many claims made in recent days about these rules, as House Democrats have debated how to structure the upcoming votes on the Senate-passed health care bill and the reconciliation “fix.”

1. What are self-executing rules?

These special procedures provide that the House— upon adoption of the special rule— is considered or “deemed” to have taken some other action as well. In the case of health care reform, the idea is that the special rule for considering the reconciliation bill would include a “deeming” provision. One form of this deeming provision could provide that when the House votes to approve the special rule for the reconciliation bill (or, alternatively, when the House votes to pass the reconciliation bill), the House is simultaneously considered to have voted for and passed the Senate-passed health care overhaul. In short, the vote on the temporary rule also provides for passage of the Senate-passed health care bill. Contrary to concerns raised on the left and the right, there’s nothing unconstitutional about the maneuver.

2. Why do majority parties use self-executing rules?

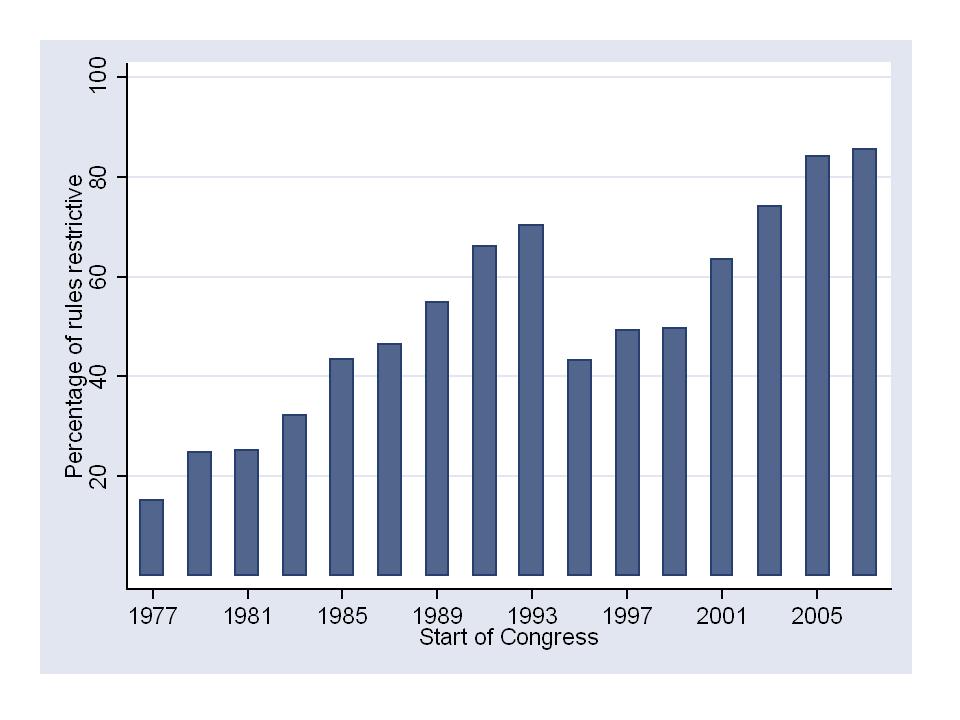

Self-executing rules are simply one form of temporary “restrictive” rules that House majorities use to structure consideration of major bills on the House floor. Restrictive rules are attractive to majority leaders as they allow them (assuming a chamber majority concurs) to structure vote choices on the chamber floor in a manner intended to protect the majority party’s favored policy outcomes from challenge. For example, restrictive rules often limit or exclude amendments on the floor if the majority party does not want to risk altering the bill or wishes to avoid asking its members to cast a tough vote. (But note, restrictive rules are not exclusively used by majority parties to attempt to move policy choices off-center; closed rules for Ways and Means tax bills can protect bipartisan compromises, for example.) As the parties have become more polarized and especially in periods of tight party margins, both Democratic and Republican majorities have turned increasingly to restrictive rules and in an increasingly creative (or, from the minority’s perspective, abusive) way. Here, I show the percentage of special rules adopted each Congress that included restrictive procedures. The trend is stark:

3. Are self-executing rules unprecedented?

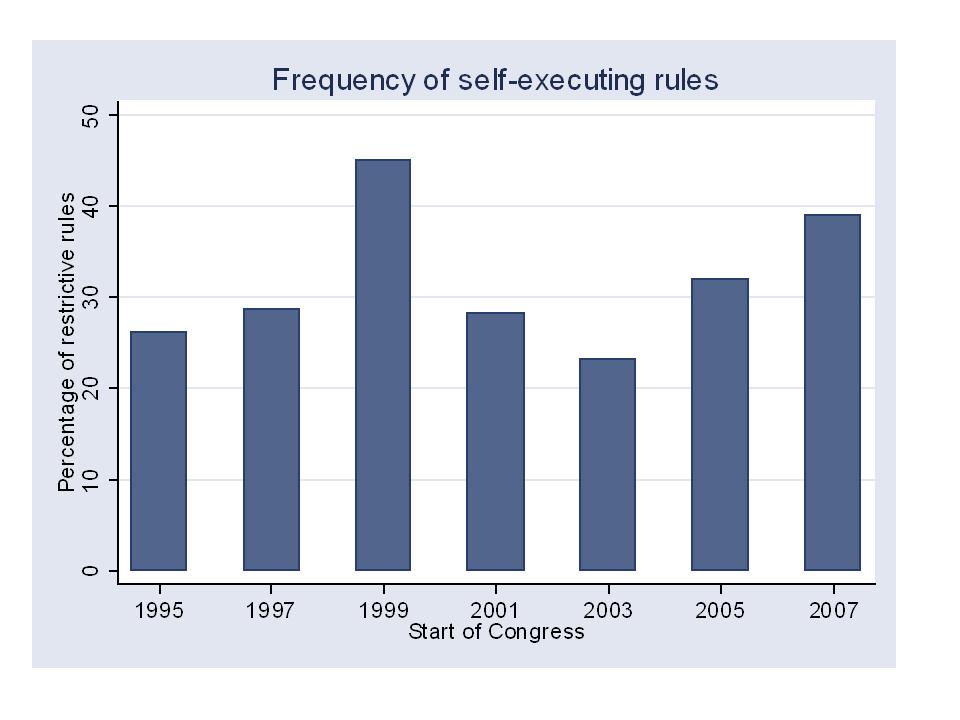

Self-executing rules certainly have precedent in the House’s repertoire of restrictive rules. My count of self-executing rules from back issues of the House Rules Committee’s Survey of Activities produces the following count (shown as the percentage of restrictive rules each Congress that included self-executing provisions):

4. Have self-executing rules been used on major bills before?

Similar to the debates over reconciliation, most observers have claimed that self-executing rules have never been used for such a major bill. Even NPR this morning intoned that self-executing rules were common, but “not on anything as big as health overhaul.” It is certainly true that self-executing rules are more often used for less controversial measures— quite often to have the House adopt Senate amendments to a House-passed bill— simply in the name of efficiency. Still, perhaps the most salient use of self-executing rules— reaching back to 1979— allows the House to avoid casting a direct vote on raising the federal debt limit. The rule for adopting the concurrent resolution on the budget typically deems as passed a measure to increase the debt ceiling. It is hard to argue that there’s any measure more central to the functioning of the nation than its ability to issue debt.

5. Why are House Democrats pursuing this strategy if it is so controversial?

As Bob Michel would remind us, most legislative games aren’t watched this closely. And, I would hazard, most close observers doubt that it will make a difference to voters whether Democrats explicitly voted for the Senate-passed bill or voted for a procedure that allowed it to be passed. But legislators sure think that it matters. They seem to think that it offers a method of avoiding blame should they be attacked come election time for their votes.

And, lest we forget, the machinations over the rule originated in House Democrats’ concern that the Senate would fail to pass the reconciliation fix, leaving Democrats on the hook for having enacted the Senate-passed bill (when they preferred a “fixed” version). A “well-crafted” self-executing rule— one that sent both the overhaul bill and the reconciliation bill to the president at once— would have allowed Democrats to bridge that increasingly wide gap of distrust between House and Senate. Alas, Congress and health care is not a game of inside baseball, and everyone is watching.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A Primer on Self-Executing Rules

March 17, 2010