The deaths of those working at Charlie Hebdo have resulted in a great deal of soul-searching in Europe. Here in Brussels, which had its own moments of anxiety following Charlie Hebdo, there is a focus on what causes radicalization and what can be done to prevent it. A lot of the discussion is on better policing (to detect and act upon threats), and improvements to the prison system (to address the apparent link between serving a prison sentence and emerging radicalized). Greater social acceptance is also being called for, to reduce discrimination against minorities and bring an end to “geographic, social, ethnic apartheid,” to quote the French prime minister.

All of this sounds right. But as an economist living in Brussels and observing the European economy, there is one big element missing from the discussion. In the aftermath of the financial and eurozone crises, unemployment has climbed from 7 percent in 2008 to 11 percent in 2013. These may not sound like large numbers, but they mean that there are an additional 9 million people out of work in the EU (see the EC’s latest report on Employment and Social Developments in Europe). There have been big increases in the number of unemployed people in Spain (3.4 million), Italy (1.4 million), and France (900,000). Numbers have risen even in some of the better performing economies such as the United Kingdom (700,000) and Poland (600,000). And while the increase is greater in the more populous countries, smaller countries have not been spared: in Bulgaria the number of unemployed has risen by 200,000, in both the Czech Republic and Slovakia, 140,000, and in Croatia, 130,000. No data are reported on Greece.

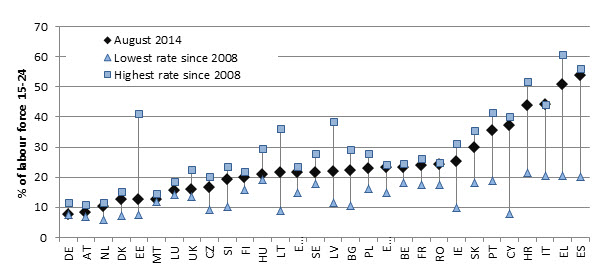

Rising unemployment has particularly affected young people. Always at a disadvantage owing to lack of work experience, young people find it harder to secure employment in a job-poor environment. As a result, youth unemployment has climbed from 15.8 percent in 2008 to 23.5 percent 2013. It now stands above 20 percent in Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Poland and Slovakia; above 30 percent in Croatia, Italy and Portugal; and above 50 percent in Greece and Spain (see Figure 1). A similar story can be told for long-term unemployment, which has doubled from 2.6 percent to 5.1 percent.

Figure 1. Youth unemployment rates in EU Member States, August 2014 and highest and lowest rates since 2008

Source: European Commission, DG Employment, 2014 Report on Employment and Social Developments in Europe, overview chapter.

Finally, there is a gender dimension to employment and unemployment that is hard to ignore. The reduction in employment since 2008 has largely affected men—over 5.8 million fewer men are in employment in 2013 compared to 2008. The equivalent number for women is 600,000. Correspondingly, male unemployment has grown. In 2013, there were 2 million more unemployed men than unemployed women (14.3 million vs. 12.1 million). Part of the reason for greater female employment is part-time work—nearly one-third of women are in part-time work (32.7 percent) compared to less than one-tenth of men (9.8 percent).

So, without drawing overly simple inferences from the very difficult labor market conditions, I find it hard to imagine a solution to Europe’s current radicalization challenges, especially among the young, that does not take unemployment into account. In addition to all the other worthwhile thoughts on the table, it is important to bring back to the center of the discussion the need to revive the European economy and reduce unemployment. Threats to the social fabric need solutions that rest on strong economic foundations.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A labor market perspective on Charlie Hebdo

February 23, 2015