In October, the Economic Development Administration (EDA) announced the designation of 31 Regional Technology and Innovation Hubs (“Tech Hubs”). Authorized through the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022, the Tech Hubs program will make coordinated, place-based investments to advance key national technologies such as artificial intelligence, clean energy, and biotechnology. Originally authorized as a $10 billion program, Tech Hubs only received a $500 million appropriation from Congress. With that funding, the EDA anticipates making up to 10 implementation grants between $50 million and $75 million each in 2024.

Tech Hubs exemplifies the federal government’s embrace of place-based economic policy. These policies outline objectives, designate funding, and design challenge competitions, but rely on cross-sector consortia of government, university, industry, and community leaders to put forward their best solutions. As we’ve learned from prior federal challenge grants, the successful implementation of place-based policies demands bottom-up creativity, capacity, and collaboration.

The architects of the Tech Hubs program are aware of this dynamic, and thus have made leadership and governance a central consideration in the competition. Yet the forms of collaborative governance required to design, finance, implement, measure, and sustain programs like Tech Hubs are still rare—partly because the United States has not historically funded major place-based programs at this scale. To guide regional implementers, this piece outlines the Tech Hubs program’s governance requirements and offers a framework for consortium governance, building on insights derived from the early implementation of a similar program: the EDA’s $1 billion Build Back Better Regional Challenge. The framework distills five key components that together capture the multidimensional nature of designing, implementing, and sustaining place-based economic strategies.

Federal grantmakers will judge Tech Hubs heavily on governance

Tech Hubs are regional innovation ecosystems that leverage multiple stakeholders and complementary efforts to catalyze local economic transformation in relatively short period of time. They are led by complex, cross-sector coalitions designed to be greater than the sum of their many parts. To coordinate and deliver against a shared regional vision, Tech Hubs need a strong governance framework that outlines leadership responsibilities, roles, division of responsibilities among members, decisionmaking processes, policies, and procedures.

The EDA has underscored the need for consortia to articulate a clear plan for their leadership, governance, and evaluation plans. As a key criterion for selecting implementation awards, the EDA will assess the strength of the consortium’s leadership team and regional innovation officer (RIO), as well as the framework and mechanisms the consortium will use to govern its activities, measure progress, build evidence, and continuously improve. Of the 80 points in the competition, “governance, leadership, and evaluation” accounts for eight. It also explicitly notes that lead entities—which will house the RIO—can apply for project-level funds that cover the costs of administration, management, and consortium-level governance.

As regions prepare for the next round of applications, they will need to articulate how their Tech Hub will coordinate its consortium and critical assets; how the consortium, its leadership, and its members will measure and evaluate success; and how the Hub will strengthen the culture and concentration of innovation in its chosen geography, among other dimensions.

The POWER framework can inform Tech Hubs governance strategies

One framework for organizing and governing place-based economic strategies is what we call the “POWER” framework. Summarizing multiple recent findings, the framework draws on insights from Brookings Metro’s examination of the early implementation of the Build Back Better Regional Challenge (BBBRC) and America Achieves’ engagements with nearly a dozen Tech Hubs applicants. The framework includes five key components, detailed below:

- Partnership structure

- Oversight and decisionmaking

- Workflow management

- Evaluation, reporting, and communications

- Resourcing and sustainability

Importantly, the EDA “expects projects to advance equity to underserved and underrepresented populations to the extent practicable,” which means that equity must be considered across all aspects of the governance framework.

- Partnership structure: Who is in the consortium and what are their roles and responsibilities?

Like the BBBRC before it, the Tech Hubs program requires applicants to pull many partners together into a consortium. In fact, the program stipulates that regional consortia must include at least one of each of the five required entity types (institutes of higher education, state or local governments, industry groups, economic development organizations, and labor organizations or workforce training organizations) and encourages two or more firms directly relevant to the consortium’s selected core technology area to participate as members. Beyond those mandates, the EDA outlines 13 additional types of institutions—from national laboratories to community development financial institutions to K-12 education systems—that could be relevant consortia members. Many of these entities tend to have long-standing trust and ties with historically excluded communities, and will be critical to communicating how consortia building is intentionally addressing the Notice of Funding Opportunity’s (NOFO) emphasis on equity and diversity.

Consortia must also designate a “lead entity” (the organization that serves as the trusted convener of the consortium to drive a cohesive regional approach and be the program administrator) and a regional innovation officer (RIO)—the “single accountable individual” driving the development and implementation of the region’s cross-sector innovation agenda. The RIO is also accountable for ensuring clear and effective governance and leadership of the consortium.

Beyond these requirements, the EDA affords considerable discretion to Tech Hubs applications. In designating consortium members, our view is that the focus should be on the quality of the partnerships and relevance of the members to the consortium’s strategy, rather than the quantity of participating members. We’ve seen wide variation in the number of consortium members by region, including many with over 30 members or up to 100. Given the potential size and efficiency tradeoffs, it is important to differentiate between committed consortium members (diverse entities integral to the success of the Hub strategy) and supporting advisors (important regional partners that are kept apprised of key developments and tapped for expertise and input). With equity a central concern, labor and community voices should be engaged and represented in the planning process and leadership structure, as both consortium members and supporting advisors.

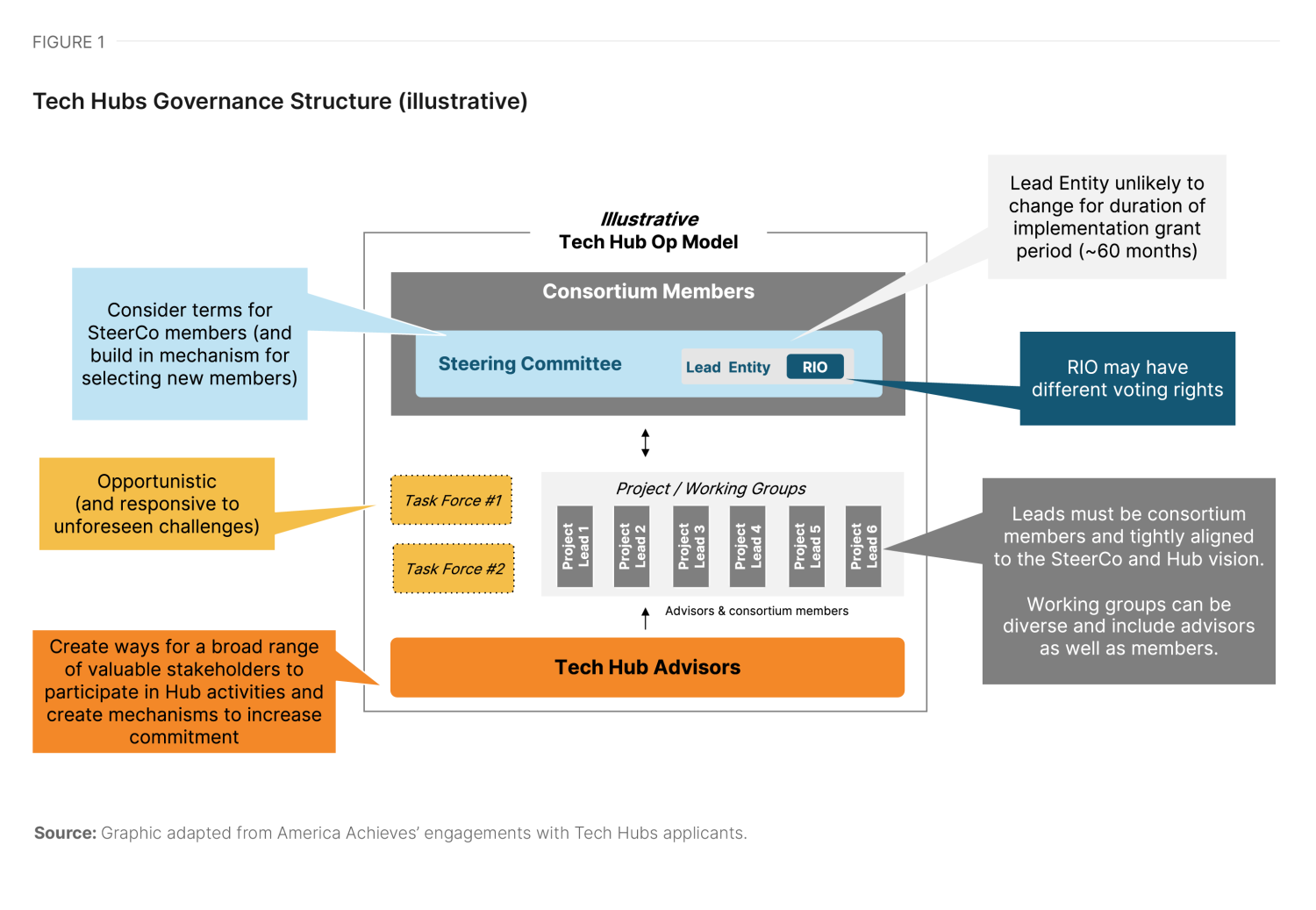

With core consortium members defined, regions then need to develop a partnership structure that supports the overall Hub strategy and promotes alignment of key stakeholders while maintaining flexibility. This could include appointing a smaller steering committee to drive efficiency, with the mandate to develop and implement the Tech Hub strategy and governance. The steering committee is often charged with setting the strategy and overseeing working groups or advisory committees aligned with the Hub’s priority initiatives, which consist of consortium members, advisors, and additional representatives. These working groups should be led by an action-oriented leader capable of driving planning and implementation and responsible for developing and implementing key initiatives within the Tech Hub strategy—informed directly by stakeholder and community engagement. Hubs may also consider “task forces” for unexpected challenges that require quick and coordinated action.

An illustrative partnership structure is depicted in Figure 1:

- Oversight and decisionmaking: How does the consortium make decisions and handle disputes?

Creating effective oversight and decisionmaking processes within the consortium is one of the most important and potentially challenging elements of governance. Consortia need to balance being action-oriented with making sure that members feel heard and empowered, and buy into the larger vision.

Tech Hub consortia will face decisions that span selecting an RIO, appointing new members and project leads, allocating budgets, adjusting scopes of work, facilitating major program changes, making site selection decisions, and changing governance procedures, among others. These decisions should be guided by a transparent decisionmaking philosophy and approach. This requires defining how much influence each consortium member and RIO should have, detailing voting protocols and mechanisms and if these differ by decision type, and articulating which decisions need to be brought to the attention of the broader group. Steering committees are an effective tool to manage these decisions and oversee the results, but it is critical that those committees are populated with a diverse set of leaders across the corporate, public, and social sectors that have respect and credibility with a diverse coalition of stakeholders.

Decisions on how to allocate resources can be especially complex given the many stakeholders, competing priorities, and potential projects that could be undertaken. The Tech Hubs program design calls for three to eight highly interconnected component projects, “such that the result is more than the sum of their parts and the projects together catalyze private sector investment and tangible outcomes for the Hub’s growth and sustainability.”

Adopting a region-first mentality among consortium members can mitigate turf wars and encourage parties to center the region’s needs over the interests of a single stakeholder. Resource allocation decisions should be rooted in the overall Hub strategy and aligned to project prioritization. To inform resource allocation discussions, consortia should develop a preliminary portfolio of projects and assess each against feasibility, impact, funding, leadership, and community buy-in measures. This assessment can reveal “must-have” projects versus those that could be deprioritized. Priority projects should have clear and capable leaders with a proven track record and the capacity to deploy funding, measure results, and adhere to federal reporting requirements. Importantly, the selected projects must be connected and coordinated to drive a multiplier impact for the region, including achieving benefits for historically excluded communities.

Because no one is “in charge” of a regional economic system, oversight and decisionmaking are nearly impossible if organizations and leaders do not have shared vision and a baseline of trust and mutual respect. Yet effective collaboration does not mean everyone always has to agree. Therefore, consortia should define a dispute resolution strategy in the event of consistent or escalating disagreements, including procuring a third-party conflict resolution specialist, assembling expert panels to provide recommendations, and holding community engagement forums to integrate the concerns and perspectives of affected stakeholders in the process. For example, to oversee its BBBRC grant, the West Virginia-based Appalachian Climate Technologies Coalition (ACT Now Coalition) developed a formal voting protocol within its leadership council consisting of community development organizations, universities, city governments, and economic development agencies.

While the EDA does not require a formal legal structure for Tech Hubs, a memorandum of understanding (MOU)—a formalized document signed by all members that outlines the agreements between parties in the collaborative effort—can codify shared consortium principles and serve as a recourse as inevitable challenges arise.

- Workflow management: How does the consortium find synergies across projects and stakeholders?

Governance frameworks must also acknowledge that Tech Hubs will eventually be tasked with delivering against a project portfolio that implicates many implementing organizations. Consortia will need to adopt strategies that cut across projects and implementing organizations if the project portfolio is to achieve results that are greater than the sum of its parts.

One lesson from the early implementation of the BBBRC is that finding synergies across individual projects is possible, but not necessarily natural. Rather, it requires new mechanisms of collaboration between project implementers and a dedicated backbone entity (most likely, the lead entity) with the ability to strategically identify opportunities for collaboration across the coalition as well as the trust and credibility to pull project implementers together. For example, Accelerate NC—a BBBRC coalition based in North Carolina—is implementing three different talent development projects to connect underserved communities to the life sciences industry: one led by an industry intermediary, one led by the community college system, and one led by universities. Each project lead is interested in leveraging the others’ efforts. But effective collaboration across the portfolio requires informal relationship building between project managers and more regular, formal meetings to discuss shared opportunities such as Accelerate NC’s new community ambassador program.

At the outset, the RIO should establish protocols to share information and manage workflow. Acknowledging meeting fatigue, this will likely involve a predictable meeting schedule and format, along with the communication of attendance expectations and meeting agendas. To drive productivity, accountability, and ongoing decisionmaking among members, these meetings can be supported by quarterly progress reports.

- Evaluation, reporting, and communications: How does the consortium track and report impact, and communicate successfully?

Tech Hubs implementation will have considerable reporting requirements, with the EDA likely to require awardees to regularly report detailed data on project engagement, outputs, and outcomes. Coalitions should think strategically about the size and composition of their support staff to meet EDA obligations, and the tools, systems, and processes to support data collection and impact measurement.

The BBBRC experience suggests that federal reporting requirements can strain the capacity of busy implementers. The Tech Hubs program, like the BBBRC, will provide funding and track outcomes at the project level. This means that the lead entity will not formally oversee outcome reporting for the project leads. That noted, there are clear efficiencies to developing coalition-wide outcome reporting templates and systems, which is why project-level funding toward “governance” is allowed and encouraged in the NOFO. Beyond the fiduciary reporting requirements, consortia should foster a culture of continuous learning and data-informed decisionmaking via clear metrics, robust evaluation processes, and ongoing risk monitoring.

Strategic internal and external communications are an important—and often overlooked—element of a Tech Hub. We touch on some internal communications considerations in the workflow management section. Beyond that, a consortium-wide collaboration, data management, and information sharing platform can further promote visibility and collaboration. One recent example is Greater St. Louis Inc.’s STL2030 Progress online tool, which tracks the region’s progress on economic initiatives such as its BBBRC grant, and situates those initiative-level outcomes within the broader performance of the regional economy.

Externally, strategic communications efforts can help raise the Hub’s profile, educate and build awareness among the community and underserved populations, and support state and private sector co-investment efforts. This can be accomplished via a mix of in-person community events that provide a forum for the broader region to provide feedback, network, and engage with the Hub’s strategy and progress. The Hub can begin by identifying key audiences, key messages, diverse spokespeople, and communications channels to deliver targeted and impactful communications.

- Resourcing and sustainability: How does the consortium secure resources and sustain the work?

It may seem strange to think about how to sustain a Tech Hubs strategy that has not yet received implementation funding. But an early lesson from the BBBRC is that sustainability planning needs to be baked in from the very beginning of the process, as the NOFO requires. The EDA will favor Tech Hubs strategies that have a clear plan for how the work will be sustained beyond the implementation grant, as will funders providing matching resources. Securing upfront funding will require long-term thinking.

The BBBRC offers early lessons here. First, some BBBRC coalitions are setting up new intermediaries that can oversee the strategy and receive funding from a variety of sources, including follow-on funding. For example, Detroit’s Global Epicenter of Mobility (GEM) coalition is being governed by the Southeastern Michigan Grants Coalition (SEMGC), a 501(c)(3) subsidiary of the Detroit Regional Partnership. The new entity provides dedicated capacity for research, technical assistance, grant compliance, and network engagement and development to bind the coalition’s strategy pillars together in a way that is designed to outlast the BBBRC. To ensure its own long-term sustainability, SEMGC will identify new sources of discretionary and formula funding opportunities to leverage and outlast existing federal funds. Similarly, Fresno DRIVE is standing up a new nonprofit entity, F3 Innovate, to serve as a sustainable governing body for all coalition activities. The Central Valley Community Foundation, which currently leads Fresno DRIVE, has worked with its other coalition partners to design a board structure for this new nonprofit entity that is representative of their collective strategic and institutional priorities.

Second, Tech Hubs applicants should position funders as key stakeholders within their partnership structure. In the BBBRC, for example, some job training programs are initially co-funded by a mix of private and public funding, but will eventually transition to a fully industry-driven, fee-for-service model to ensure sustainability. Such a strategy requires corporate champions that are brought into the governing coalition as soon as possible.

The path forward requires significant regional capacity

Tech Hubs are composed of multiple actors and projects that drive toward a collective and transformational vision. It demands adaptive leadership, a shared regional “north star,” deep industry engagement, targeted big-bet investments, and a willingness to continuously evolve.

In the planning process, it can be tempting to focus on the “tech” side of Tech Hubs while underinvesting in the “hub” side. But the process of building a world-beating technology cluster is multi-actor, multi-sector, long-term, and regional. That is why Phase 2 applicants should consider using the POWER framework to answer tough but critical governance questions at the outset, and thereby set themselves up for success in supercharging their efforts to create globally competitive and inclusive regional economies.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors acknowledge Alan Berube and Mark Muro at Brookings Metro for their feedback on this draft, and Monica Chellam at America Achieves for developing the graphic and providing feedback on the article.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A governance framework for regions competing for Tech Hubs and other new federal investments

December 20, 2023