The 1990s were a decade of intensive peace process negotiations between Israel and its Arab neighbors. In Madrid and Oslo and Shepherdstown and Camp David, two American presidents tried to bring peace to the Middle East.

In the end it was mostly a failure, with one exception: the Jordan-Israel peace treaty of October 26, 1994. Twenty-five years ago, the treaty was signed in the Wadi Arava along the border between the two countries with President Bill Clinton as the witness. It has endured because it has strategic value to both countries and the United States.

Quiet beginnings

The treaty is very much a derivative of the Oslo process. When the secret talks between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) were divulged in 1993, Jordan’s King Hussein felt betrayed. For years he had been secretly meeting with the Israelis to broker peace; now he discovered that they were secretly meeting with the Palestinians and making a deal without consulting him. The PLO, fellow Arabs, had not consulted the king either. He was devastated.

I was in Aqaba when Clinton hosted the now iconic handshake at the White House between Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and PLO leader Yasser Arafat. The mood in the palace was grim. Clinton had sent me and a team of experts to assess Jordanian compliance with the United Nations sanctions on Iraq. Jordan’s tilt toward Iraq in the 1990 Kuwait crisis had poisoned American-Jordanian relations. Aid had been stopped, military support and logistics cut off, and the Jordanians’ only port at Aqaba was under quarantine to check for traffic transiting to Iraq via Jordan. The new administration wanted to see if the page could be turned on Iraq and the U.S. relationship with Jordan restored to normal. I visited the border crossing to see if the Jordanians were actually ensuring only U.N.-approved humanitarian goods were entering Iraq.

In September 1993, Rabin secretly came across the border from Eilat to Aqaba to address King Hussein’s concerns and assure the Jordanians that they would be kept informed about the future of the Oslo process. The meeting was arranged by Efraim Halevy, the deputy director of the Israeli intelligence service, the Mossad. Hussein had been dealing with the Mossad and Halevy for years as a trusted clandestine back-channel. He would be a key player in the treaty’s consummation.

Jordan would not be alone.

Gradually over the fall and winter of 1993-94, King Hussein and his brother Crown Prince Hassan bin Talal recognized that the Israeli-Palestinian talks were actually an excellent opportunity for Jordan. Hassan was to be the king’s closest advisor in the talks with Rabin and Halevy. Jordan had long held back from a peace treaty with Israel because it did not want to get in front of the Palestinians. It did not want a separate treaty with Israel, like President Anwar Sadat had done for Egypt. But now Arafat was engaging in direct talks with the Israelis to make a peace agreement: Jordan would not be alone. Even the Syrians were engaging with Israel via the Americans. Jordan was free to negotiate a peace treaty with Israel after decades of clandestine contacts begun by Hussein’s grandfather King Abdullah without fear of a backlash from the other Arabs.

Moreover, the negotiation of a peace treaty with Israel would also open the way for a rapid restoration of ties with Washington. Clinton supported the peace process enthusiastically. A Jordanian treaty would get his support and help him sell the revival of bilateral relations with Jordan to Americans still angry over the Iraq war, especially in Congress. The king still did not truly grasp how badly his ties to Saddam Hussein had tarnished his image with the Americans.

In April 1994, King Hussein sent for Halevy to come across the Jordan River for another secret meeting. The king told him that he was ready to go for a peace treaty and engage in direct talks to settle the borders and all other issues. He wanted to move quickly. He also wanted Israeli help with Washington to restore relations, including the resumption of military aid and spare parts as well as delivery of a squadron of F-16 jet fighters for the Royal Jordanian Air Force.

The king also had tight constraints on how he wanted the negotiations to proceed. The Americans would not be in the room and not mediate the talks. Jordan and Israel would keep the Americans informed, but the king did not want Washington using its leverage in a negotiation process given the Americans’ closer ties to Israel.

He also wanted Halevy as the principal Israeli negotiator. Israeli Foreign Minister Shimon Peres was to be excluded from the talks. Hussein had bitter experience with Peres and believed he was a publicity seeker who could not keep a secret. Hussein was particularly upset that Peres could not deliver Israeli support for a secret agreement the two had signed in London in 1987. He also was well aware that Rabin and Peres were rivals.

It was an extraordinary message for the Mossad officer to deliver to Rabin. The timing was also bad: Two terrible terrorist attacks had just occurred in Israel. Some were erroneously blaming Jordan for harboring the terrorists’ leaders. But Rabin had met with the king secretly for almost two decades, and he was impressed by the message. The first round of talks began.

Trusted partners

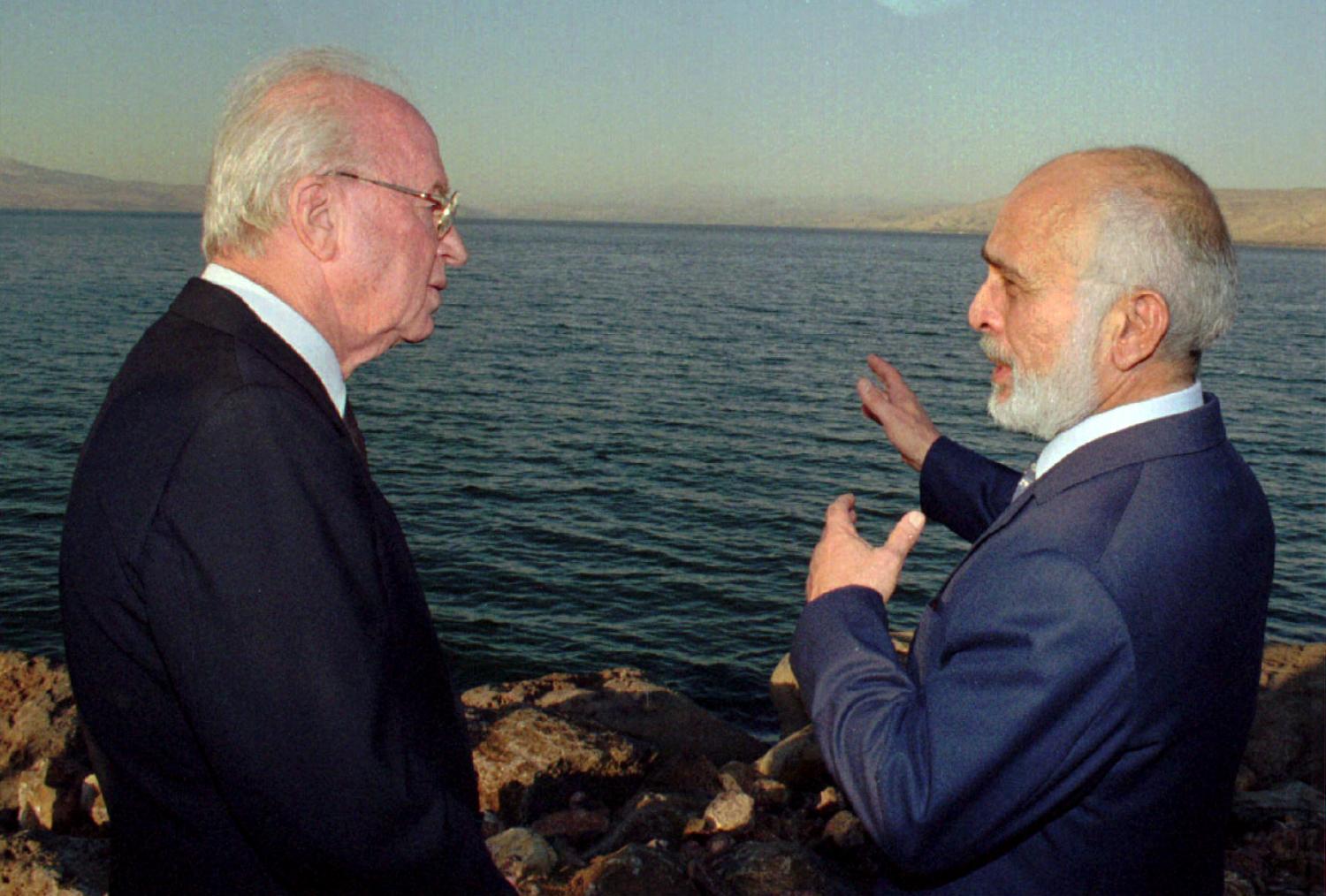

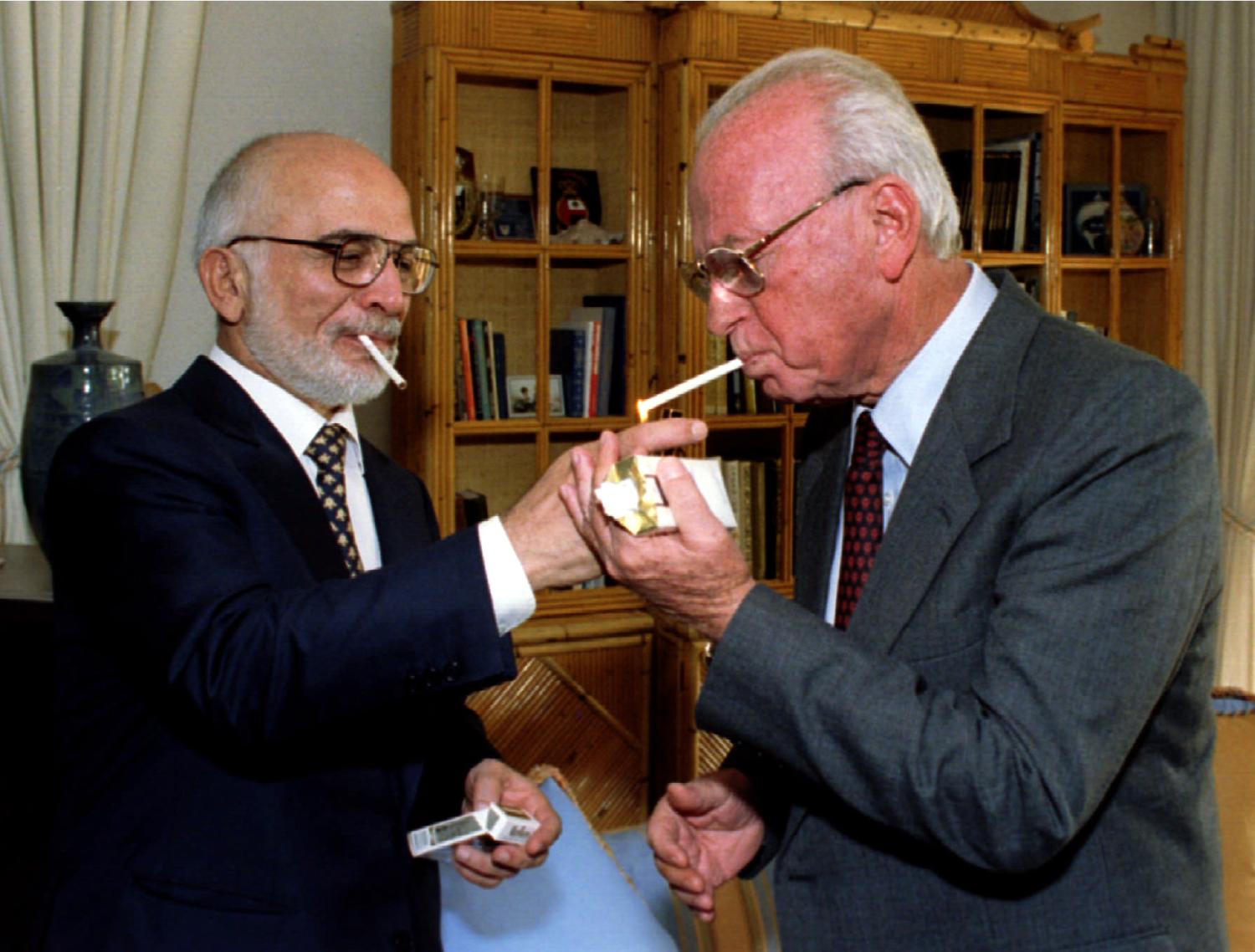

The Rabin-Hussein relationship was crucial to the success of the negotiations. Both trusted the other. Hussein saw Rabin as a military man who had the security issues under his command. He was convinced that he had a unique opportunity to get a peace treaty and Rabin was central to the opening.

The king also saw the negotiation process as almost more of a religious experience than a diplomatic solution to the passions of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

The king also saw the negotiation process as almost more of a religious experience than a diplomatic solution to the passions of the Arab-Israeli conflict. He spoke movingly of restoring peace between the children of Abraham. He wanted a warm peace, not the cold peace between Egypt and Israel.

Jerusalem was also a core issue for the Hashemite family. Despite losing physical control of East Jerusalem in 1967, the king had retained influence in the Muslim institutions that administered the holy sites in the city. The preservation of Jordan’s role in the administration of the third holiest city of Islam was a very high priority of Hussein then, and still is for his son King Abdullah today. In another secret meeting in May 1994, in the king’s home in London, Rabin assured the king that Israel would abide by the Hashemite link to the city. It would be explicitly mentioned in the treaty’s article 9. It was the crucial breakthrough.

Meanwhile, in Washington

In Washington, the Clinton administration closely monitored the progress in the Jordanian track. Initially there was some skepticism that Hussein was really prepared for a treaty; he had held back before. Also, the king preferred to talk to the Americans through the Central Intelligence Agency rather than the State Department. Halevy, too, was more comfortable with the CIA. As the national intelligence officer for the Near East and South Asia back at the CIA, I found that I was better informed on the process than my colleagues in Foggy Bottom, often knowing the latest sooner than they.

In June, King Hussein came to Washington to tell Clinton exactly the progress made and lobby for resuming aid. He asked Rabin to send Halevy to help behind the scenes. The Jordanians provided the White House with a detailed and lengthy memorandum on the bilateral issues they wanted addressed.

On June 22, the king meet with the president. Clinton had studied the Jordanian wish list carefully. The top priority was for debt forgiveness, amounting to $700 million dollars. Clinton told Hussein that this would be a tough lift on Capitol Hill. If Hussein would meet Rabin at a public ceremony in the White House hosted by the president, Clinton said he could get the debt relief and progress on Jordan’s other requests.

The king told his aides that this was the best meeting he had had with an American president since his first with Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1959. On July 9, the king told the Jordanian parliament that it was time for an end to the state of war with Israel and for a public meeting with the Israeli leadership. He wanted the meeting to take place in the region.

The Americans wanted it in Washington. They were dangling fulfillment of Jordan’s wish list but wanted the dramatic public pictures to be in their capital. Hussein reluctantly agreed. The Jordanian and Israeli peace teams met publicly on the border to start the rollout, followed by a foreign ministers meeting at the Dead Sea in Jordan — a way to bring Peres into the photo op but not the negotiations.

Those went on behind the scenes to craft a document laying out the principals that would frame the treaty. The Washington Declaration was very closely held. The Americans got a copy only on the night before the White House ceremony.

Success

On July 25, 1994, Clinton read the declaration on the White House lawn and Rabin and Hussein signed it. It terminated the state of war. Israel formally undertook to respect the special role of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan in the Muslim holy shrines in Jerusalem. All three gave speeches, but the king’s address got the most attention. His speech included a clear and unqualified statement that the state of war was over. He spoke of the realization of peace as the fulfillment of his life-long dream.

At the banquet that night, Clinton spoke of the king’s extraordinary courage in pursuit of peace. He compared him to his grandfather, who had been assassinated for his talks with Israel. Hussein had witnessed King Abdullah’s murder first-hand and had just narrowly escaped death himself — in fact, the assassin’s bullet ricocheted off a medal his grandfather had insisted he wear that day. Hussein was visibly moved.

The next day, Rabin and Hussein addressed a joint session of Congress. Hussein spoke about his grandfather’s commitment to peace. “I have pledged my life to fulfilling his dream.” Both received standing ovations. Behind the scenes, Halevy was lobbying Congress for debt relief. He returned to the region on the royal aircraft with the king and queen.

The king’s jet was given clearance to overfly Israel en route to Amman, one of the agreements in the Washington Declaration. He was escorted by Israeli F-15 fighters. The aircraft flew over Jerusalem and circled it several times at 1,000 feet. It was the first time Hussein had looked at the city since 1967. The queen said it was a deeply moving moment, especially as they looked down at the Dome of the Rock.

Three months of intense negotiations began to finalize a treaty. Teams from the two countries met every day, mostly at the crown prince’s house in Aqaba. Hassan supervised the day-to-day talks for his brother.

The toughest issues were land and water. In the years after the 1967 war, Israel had encroached on Jordan’s land south of the Dead Sea, taking 380 square kilometers of land, roughly the size of the Gaza Strip but mostly empty of people. On October 12, Rabin and Hussein reached agreement on a compromise that Hassan and Halevy had worked out. The border would be slightly adjusted, but the Jordanians would get back the land. Jordan would also get a generous increase in water from the Jordan Valley.

The final issues were addressed at another Rabin-Hussein summit meeting in Amman on the evening of October 16. The two leaders got down on their hands and knees to pour over a large map of the entire border from north to south and personally delineated the line. Two small areas got special treatment: Israel would lease the two areas from Jordan so Israeli farmers could continue access to their cultivation. By 4am, it was done.

On October 26, 1994, Clinton witnessed the signing of the treaty on the border by the prime ministers of Israel and Jordan. It was only the second visit to Jordan by a sitting American president. (Nixon had visited in 1974 in a desperate effort to avoid impeachment by highlighting his role in the Middle East after the October 1973 war.)

In Amman, demonstrators waved black flags to protest the treaty. Many Jordanians felt it was dishonorable to make peace with Israel while the occupation of the West Bank continued. Some argue that it legitimates the Israeli occupation. It has gotten progressively more unpopular in the 25 years since the signing ceremony.

Rabin’s assassination a year later removed Hussein’s partner in peace. He attended the funeral in Jerusalem, his first visit to the city since the 1967 war. Two years later, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu dispatched a Mossad hit team to Amman to poison a Hamas leader. The botched murder attempt created a crisis in the new peace, and Halevy had to be called back from his new job in Brussels as ambassador to the European Union to smooth out the disaster and get the Mossad team released. He would then be appointed the head of the Mossad.

The king sent Crown Prince Hassan to Washington to assess the damage. Clinton used his leverage to get the crisis resolved. Hussein never trusted or respected Netanyahu after it, and the peace has been cold ever since. It was a defining moment.

But Hussein’s strategic goal of restoring bilateral relations with the United States was achieved. In 1995, I accompanied Secretary of Defense William Perry to Amman where he announced the forthcoming delivery of a squadron of F-16s to Jordan. Perry called the country the “lynchpin” of the Middle East. Debt forgiveness was already done. And in December 1999, I traveled with Clinton and three former presidents to attend Hussein’s funeral in Amman in a strong demonstration of America’s commitment to Jordan.

The Trump administration has tilted dramatically toward Israel on all the issues that concern Jordanians about the future of the Palestinian issue, especially the status of Jerusalem. The movement of the American embassy to Jerusalem was a particularly important shock to the peace treaty. If Israel begins to annex parts of the West Bank, as Netanyahu has promised, the Jordanians will be in a corner. The treaty may be more endangered today than ever before.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

25 years on, remembering the path to peace for Jordan and Israel

October 23, 2019