If there is one thing Greece and its creditors fully agree on, it is that the country desperately needs to recover. As for the obstacles blocking a turnaround, the dominant view is that the Greek government ultimately objects to all of the economic policy prescriptions being proposed—structural reforms included—because of their unbearable political costs. Fiscal adjustment in particular requires painful wage cuts both in public and private sector. Already, the so-called “internal devaluation” led to a spiral of cuts that lowered GDP growth, further complicating efforts to solve Greece’s problems.

But what if the root of the current stagnation is not mainly due to the high and painful political price of economic reforms, but is instead at its heart a problem of systemic political dysfunction?

Politics leading to economic crisis?

Over the past ten years, the average period of a sitting government in Greece has been around two years, typically triggered by calling early elections, even though the country’s constitution defines four years as the normal period before new elections should be called. Certainly the economic crisis has aggravated this short-termism, prompting both political radicalization, a fraying of political coalitions, and the proliferation small parties.

Perhaps it is time to investigate the role of politics in accelerating this severe crisis, now that the evaluation of the first part of the 3rd bail-out program has reached its unsatisfying conclusion. Since the crisis began, absolutely no reforms to the domestic political system—say, to the constitution, the electoral law, parliamentary procedures in law making, and so on—have been undertaken.

The fragmented political market

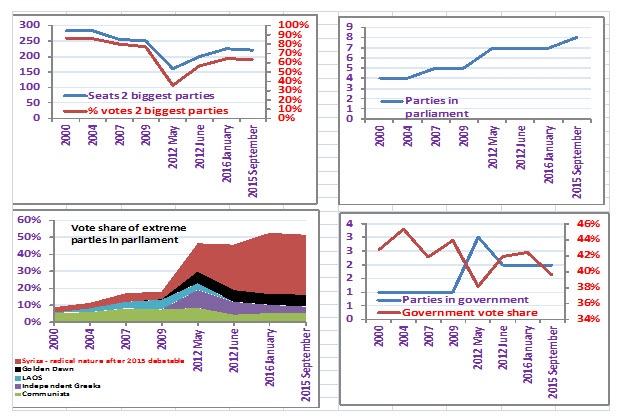

In particular, ideological factionalism, party disunity in the parliament, weak government and, last but not least, opposition voting share have all increased during the crisis. This has stymied economic recovery and is a persistent challenge both for Greeks as well as for creditors (figure 1). These developments are in line with the decline in trust Greeks feel for their government as well as their skepticism about EU institutions as evidenced in annual Eurobarometer surveys.

Figure 1. Political fragmentation and risk in Greece

Source: T. Pelagidis & M. Mitsopoulos, Political fragmentation and risk as a source of economic underperformance, Managerial and Decision Economics, forthcoming. LAOS, Independent Greeks are far right and Golden Dawn a Nazi party. The extremism of all votes that support Syriza can be credibly questioned, especially after the 2015 referendum and the signing of the 3rd assistance program MoU.

These developments reflect the corrosive effect the crisis in Greece has had, not only on the economy, but also on trust in institutions and the capacity of the political establishment to advance meaningful reforms, most of the time highly demanded by the creditors. An ill-fated execution of the initial Memorandum of Understanding back in 2010 has weakened the pro-reform political forces and stoked populist extremism. Such extremism is deeply rooted in the traditions of the clientelistic politics that were a key cause of the crisis in the first place. The European Union’s inability to handle instances where domestic politics were against developing national institutions aligned with EU standards was clumsily resolved by introducing the “Grexit” threat. This in turn only amplified the undesirable political developments that already were in motion and further imperiled economic prospects.

Politics, Europe and the threat of “exits”

The bad taste left over from the Grexit debacle underscores the need for Europe to work out a way to handle such unfortunate events, now and in the future, in a manner that both supports “convergence in institutions” among the member states and that obviates the need to wield the threat of expulsion. Even while great progress has been achieved in the area of the banking union and fiscal supervision, progressing beyond loose coordination of economic policies is essential to removing the “Grexit” tactic as a tactic of brinksmanship. This applies in the case Greece as well as in any other potential cases.

At this stage, the only remaining hope for Greece is that, as radical and populist politicians become ever more discredited, a reform-oriented political entity with the ability to govern and deliver will emerge. At the same time, extreme poverty, loss of wealth and income, over taxation and low expectations for the future among most citizens have to (miraculously) translate into concrete support. This is the only way the electorate can regain some sort of normality in their daily lives. Europe could facilitate this by taking serious initiatives toward common decision-making in basic dimensions of economic policy. The EU could, for example, give regulatory and institutional convergence among member state more prominence than in the past and could allow slightly more fiscal headroom when projected policies are in the right direction. Otherwise, Brexit and Grexit risks will tend to become a permanent feature and a constant nightmare for Europe.

Commentary

European disunity, politics, and preventing exits

June 15, 2016