Transparency International (TI), the international anti-corruption NGO, just released its annual Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). There are no big surprises…since corruption does not tend to change dramatically from one year to the next. Yet, it is certainly worth reviewing the new data.

New Zealand, Denmark, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland and Finland are at the top. At the other end of the spectrum, one finds well over a dozen countries regarded by the TI index as rife with corruption, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Sudan, Chad, Somalia, Myanmar (Burma), Equatorial Guinea, Venezuela, Haiti, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Conflict is rife in some; authoritarianism and extractive industries are dominant in others.

One is not surprised either by today’s front page revelation in the Washington Post on the Afghan minister of mines being accused by U.S. officials of taking roughly $30 million dollars in bribes from a Chinese firm.

Further debate on aid effectiveness may be spurred by these revelations of brazen corruption in Afghanistan, or by the data on the extent of corruption in other poorly performing countries. This would be a healthy debate, if done properly.

In fact, there are at least three major efforts underway in the U.S. to review official foreign aid strategy and programs, one from the White House, known as the Presidential Study Directive on Global Development Policy (headed by the NSC’s General Jim Jones and NEC’s Larry Summers); another from the State Department, the so called Quadrennial Diplomacy and Development Review (QDDR) under the leadership of Secretary Clinton, and yet another in the U.S. Congress, the Initiating Foreign Assistance Reform Act of 2009. Indicators ought to be central to such evidence-driven policy making. They should be used judiciously, being aware that they are subject to margins of error.

The evidence is sobering. Looking at the indices on corruption, it is evident that countries where the U.S. has channeled large amounts of development aid, such as Iraq, Afghanistan, Sudan and Pakistan, and to a large extent Nigeria, Egypt and Kenya, are not faring well on corruption.

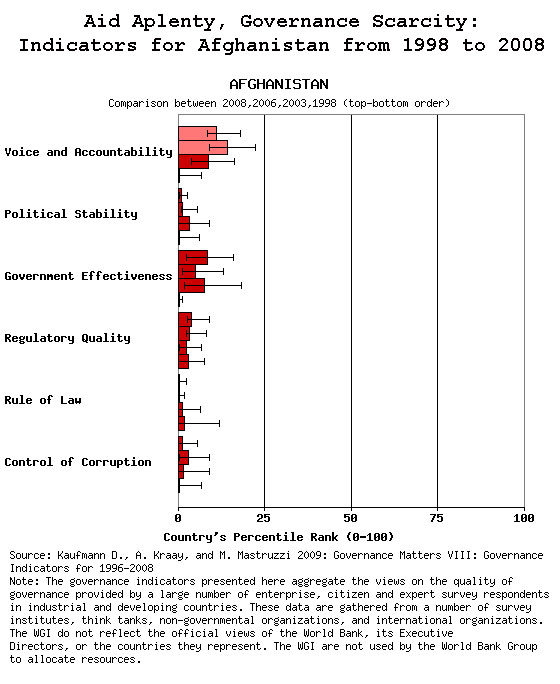

And if we recognize that corruption is often a symptom of fundamental governance failings, forcing us to review the data on governance more generally in these countries, the magnitude of the challenge becomes clearer. As the chart on Afghanistan makes clear, and even if we note that some progress in integrity has taken place in selected institutions, such as policy, misgovernance has been rife across the spectrum for some time.

But it would be simplistic to jump from such stark reality of corruption to a rationalization for pulling back from development aid. That would be misguided for the U.S., and for other bilateral or multilateral donor agencies. Yet, business as usual in development aid cannot continue unchallenged either.

It is critical to probe below the surface and ask tough questions, with studied and frank answers. Let me suggest a set of five:

1. Even if there are high levels of corruption in the country when the U.S. (or other donors) provides aid, is there evidence of improvements, and of reformist leadership committed to future changes, so that there is a likelihood of sustained movement in the right direction? In other words, one ought not concentrate merely on current levels of corruption, even if dire.

2. What is the evidence and what lessons have been learned from those cases in which significant aid flows to non-corrupt countries? The focus on the less-than-stellar performance of development aid in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan can blindside many to the fact that there are other country cases as well, with different lessons.

Colombia has been a large recipient of development aid, and over the past decade it has made notable improvements in controlling corruption. In Ethiopia, another relatively large aid recipient, corruption is not endemic. Of course, both countries have other challenges (manifested differently), such as in the democratic accountability and human rights front. Liberia, through resolute leadership, provides another potentially interesting case study in improvement in the short term.

3. Are the aid programs actually helping promote improved governance and anti-corruption in meaningful ways in recipient countries, with full country leadership and partnership? Or are they perpetuating corrupt governments, leaders and institutions instead? Or they are simply being wasted and not making a difference (while these programs and funds could be making a big difference elsewhere)?

4. Where the public leadership and central government is entrenched and highly corrupt, what workable alternatives to working with central governments ought to be advanced further? What has worked, and what has not? Concretely, there is a need to spell out in detail the various possible modalities of aid that may support a revamped anticorruption effort in settings like Afghanistan, Pakistan and Kenya, for instance.

5. What exposure to corruption do the very projects and funds provided by development aid have? This is a popular concern, and is a relevant one, since we know that some aid funds are diverted. Yet, the narrow focus on this fiduciary issue by many aid donors has often meant that the all-important development effectiveness concerns discussed in the previous four sets of questions have been downplayed.

Further, funds and corruption are both fungible and adaptable. The more effective one aid agency is in trying to safeguard every dollar they provide in aid (even though fully “ringfencing projects” is utopia), the more corruption will migrate to other projects and funds if the systemic issues remain unaddressed.

Needless to say, corruption cannot be the only lens by which aid effectiveness is assessed. It is often a symptom of broader governance failures. Yet the broader prism of governance, encompassing corruption, rule of law, voice and accountability, rule of law, and related institutional dimensions, ought to be central. And one likely conclusion from a serious review of development effectiveness, if governance and corruption are taken head on, would be that further selectivity in aid programs is warranted. But the devil will be in the details. And in the polity.

Further consistency in applying criteria for assisting countries is also sorely needed. The treatment of similarly corrupt governments by official donor agencies tends to be very different depending on the strategic “geo-oil-political” relevance of the aid recipient country in question, which further undermines credibility and impact of donor aid.

This story in yesterday’s New York Times on the politics of corruption between the U.S. and Equatorial Guinea is a stark reminder that striving toward more consistency in applying standards should be a key part of a development aid effectiveness review.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Corruption Index Today, Election Tomorrow, Aid Revamp the Day After?

November 18, 2009