With upsets galore, many college basketball fans are looking at busted brackets as we approach the Final Four of both the men’s and women’s annual NCAA college basketball tournament known as March Madness. That got us to thinking: What upsets might occur if these colleges and universities competed on the outcomes of their alumni rather than on the court?

Last fall, the Metropolitan Policy Program released an updated ranking system for colleges and universities based on a value-added method for assessing how alumni from over 3,000 U.S. two- and four-year schools perform on earnings 10 years after they first enroll. To do so, we first estimate how college alumni might perform based on a set of school and student characteristics that include average student family income, test scores of incoming students, racial makeup, the geographic location of a school, and other variables. We then compare these estimates to the actual earnings of alumni, sourced from the Obama administration’s recently released College Scorecard.

Colleges and universities with higher-than-expected alumni earnings given their school and student characteristics have a higher percentile ranking. In this system, a state school that may have a lower-scoring student body in terms of incoming test scores or students from more disadvantaged backgrounds can outperform an Ivy League university if that state school produces alumni whose earnings far exceed what we would expect given school and student characteristics.

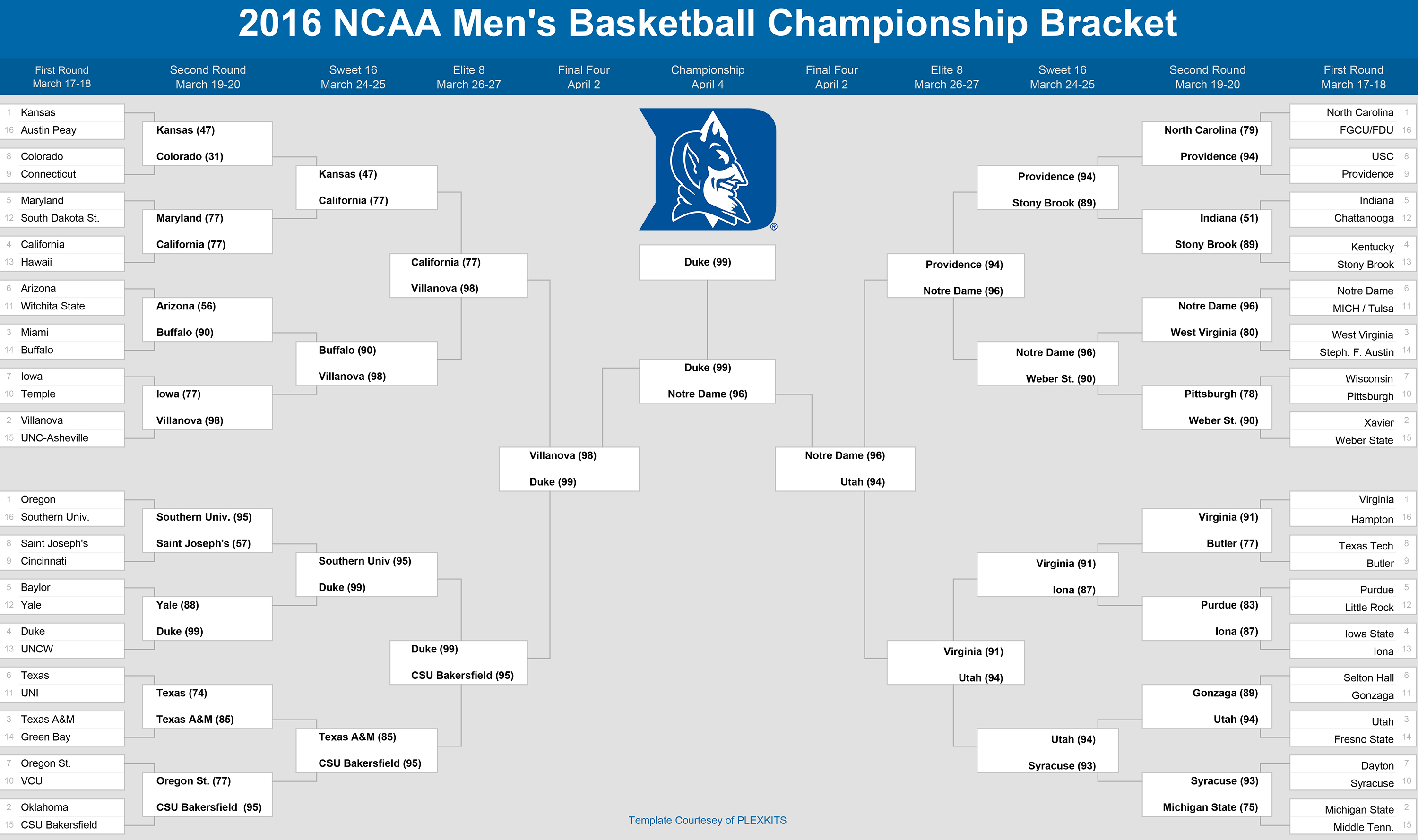

We filled out brackets on the men’s and the women’s side of the NCAA tournament using the percentile rankings for the value-added measure. If a school’s value-added ranking is higher than its competitor, it wins that round and moves on. In the case that two schools have identical percentile rankings, we look to the actual earnings of alumni as the tie-breaker.

The tournament winners for both the women’s and men’s brackets don’t resemble the outcomes in either of the actual tourneys, despite a similar number of upsets. On the women’s side, matchups won by economic outcomes of alumni rather than box scores by student-athletes led to only a few top basketball teams—Notre Dame, Stanford, Texas A&M, UCLA, and Michigan State—making the third round. More upsets occurred in the bracket on the men’s side, with only number two seeds Villanova and Virginia, number three seed Texas A&M, and number four seeds Cal and Duke making it to our version of the Sweet Sixteen.

This isn’t to say that basketball powerhouses don’t have strong academics—many of them do—but our method compares the expected mid-career earnings of alumni given student body and school characteristics to actual earnings of attendees and does so in an apples to apples way. As a result, basketball underdogs like CSU Bakersfield and Providence on the men’s side and James Madison and Penn on the women’s side competed deep into our version of the tournament.

The college quality Final Four on the men’s side features four familiar basketball programs—Notre Dame, Utah, Villanova, and our eventual tournament winner, Duke. On the women’s side upsets abound, creating a final four with only one highly ranked basketball team, Stanford, and three upsets in Princeton, St. John’s, and our eventual tournament winner, BYU.

Both BYU and Duke have academic strengths that we found accounted for a large share of success on the value-added metric across institutions, which includes a curriculum that focuses on high-value science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) and strong graduation rates. Yet for both Duke and BYU the largest component of their value-added scores are their strong “x-factors,” which suggests that Duke and BYU have qualities that are difficult to measure—such as academic and career counseling or strong alumni networks—that allow students to succeed after leaving campus but aren’t reflected in the data.

Unlike in the real March Madness, there are countless more winners when considering economic success as a result of attending college, despite increasing costs. Going to college significantly increases earnings power and the likelihood of employment for attendees, among other positive economic outcomes. And while considering how a college or university contributes to the economic success of its alumni isn’t as exciting as watching two teams going down to the wire on the hardwood, college rankings may be of more interest to students and their families thinking about which sweatshirt to buy in the fall and which team to root for next year.

Research Intern Mariah Harvey contributed to this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

March Madness of college quality judges schools on alumni outcomes

March 30, 2016