Identity politics seem to have made a 180-degree reversal this week as Hillary Clinton and Marco Rubio announced their candidacies for 2016. In the last two presidential elections, Democratic victories were propelled by racial minorities and the young, while Republicans relied heavily on older whites. In both cases, the candidates’ own demographic identities reflected their parties’ bases (President Obama versus John McCain and Mitt Romney, respectively). In this round it is conceivable that Clinton, a white baby-boom senior, will be the Democratic standard bearer and, Rubio, a Hispanic Gen Xer, could carry the GOP mantle. Would that make the 2016 campaign less polarized than 2012’s? I think not—in light of the cultural generation gap that has emerged in American politics and society at large.

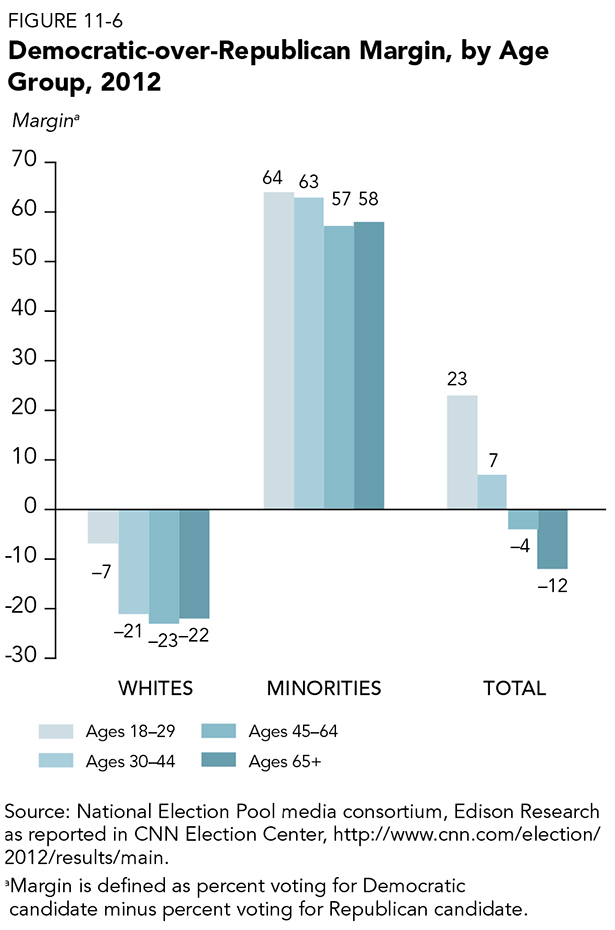

The gap has already been made clear in presidential politics. In 2012, Obama received eight of every 10 minority votes cast while Romney received nine of every 10 of his votes from whites. This race disparity explains voting differences by age. Because racial minorities are more heavily represented among youth, Obama won among voters under age 45, while Romney had the advantage among mostly white baby boomers and seniors (see figure).

Underlying these trends is an emerging cultural generation gap, which I write about in my book “Diversity Explosion.” This gap reflects the increasing social distance between older whites—baby boomers and seniors—and younger, more racially diverse Gen Xers and millennials. The former grew up in the homogenous 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, years of low immigration, segregated minorities, and little interaction between the large white population and the mostly black racial minority population. As white baby boomers became older and more concerned with their own finances and economic well-being, they became more conservative on many dimensions, including voting and party identification. Surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center and others show boomers and seniors to be less open to new immigrant groups and minorities, and more averse to a bigger government with more services (and higher taxes) than younger more diverse generations who, in addition to favoring greater government support for domestic programs, are more progressive on an array of social issues, from same-sex marriage to immigration reform. In essence, older white Americans do not see younger Americans as “their” children and grandchildren and have lost a common connection.

This perception needs to be corrected since, as the younger white population declines and older whites retire from the labor force, racial minorities, especially growing new minorities—Hispanics, Asians, and multiracial Americans—are more crucial to the nation’s future. The continued divided politics of race and age simply reinforce this old misperception.

But it is not likely that even a Clinton-Rubio contest will move the 2016 election debate toward the center. Clinton will do her best to appeal to the Democrats’ emerging base: racial minorities, young people, and selected white population groups—such as single college-graduate women—who are least inclined to vote Republican. She must promise to support the kinds of domestic programs such as the Affordable Care Act and early childhood education that are crucial to that base. Rubio cannot afford to alienate white baby boomers and seniors, now central to a Republican win, and will be cautious about how he discusses immigration reform, making sure to place emphasis on securing the borders. In essence, identity politics could put both candidates on the defensive—more concerned with alienating their long-held political supporters than expanding their bases to include more people like themselves.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Hillary Clinton, Marco Rubio, and America’s cultural generation gap

April 14, 2015