Seattle Mayor Ed Murray recently announced a plan to raise the minimum wage in his city to $15/hour over the next few years. The plan emerged from a special business/labor advisory committee, approved by 21 out of 24 its members, after four months of hearings, academic studies, and debate . The measure awaits approval by the City Council, but the move to $15/hour in Seattle seems well underway.

Seattle may be the first, but it won’t be the last, city to take this bold step. Granted, there were some peculiarities in Seattle’s case, including a $15/hour minimum wage ballot initiative that succeeded in the nearby city of SeaTac in November, and the election of a new Socialist Party Seattle City Council member who campaigned on the issue. But with inequality taking center stage as a political issue in big cities around the country, mayors, businesses, and labor advocates are watching Seattle closely.

However, the focus on big cities shouldn’t obscure the fact that wages are a function of regional economics. Seattle is indeed a big city, with 635,000 residents and (by our count) nearly 500,000 jobs. But it’s only part of King County, Washington, which has roughly 2 million residents and more than 1 million jobs. And King County is just one of three counties that make up the wider Seattle metropolitan area, with a population of 3.5 million and 1.8 million jobs.

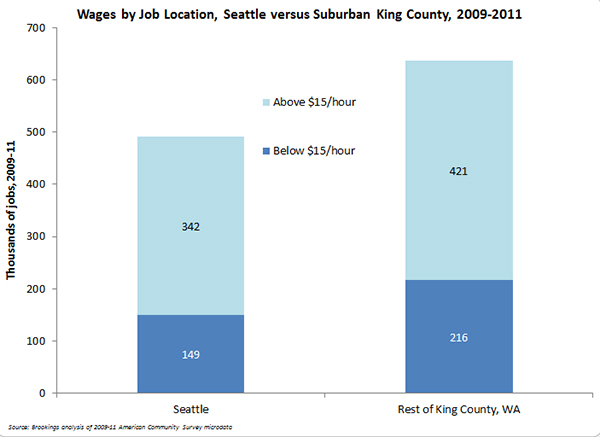

While low-wage jobs are prevalent in Seattle, they’re even more prevalent in its nearby suburbs. Using data from the American Community Survey, my colleague Sid Kulkarni and I calculated that between 2009 and 2011, there were on average 149,000 jobs (full-time and part-time) in the city of Seattle that paid less than $15/hour. Over the same period, the remainder of King County had an average of 216,000 jobs that paid hourly wages below that threshold. These low-wage jobs represented 30 percent of all jobs in Seattle, and 34 percent of all jobs in the rest of King County.

It stands to reason that low-wage jobs are more suburban than high-wage jobs. Typically, the highest-value jobs in a region are located in central cities. High-paying sectors like finance, advanced health care, information technology (Redmond notwithstanding), and higher education tend to be more urban than suburban. Yes, cities also have lots of low-paying jobs in hospitality and retail, but so do suburbs. Those jobs tend to follow people, and most people in major metro areas live in suburbs. As my colleague Elizabeth Kneebone has found, as population sprawls, so does low-wage work.

To be sure, many people who live in the King County suburbs of Seattle will benefit from a $15/hour Seattle minimum wage, because they work in the city. According to a University of Washington study conducted for Mayor Murray’s Income Inequality Advisory Committee, fully four in 10 people who earn less than $15/hour working in Seattle jobs—and who would thus presumably benefit from the minimum wage increase—live outside of the city. That’s particularly important in a region like Greater Seattle, where suburbs are home to most of the poor. At the same time, the UW study finds that nearly as many Seattle residents in sub-$15/hour jobs work outside the city limits.

None of this amounts to an argument against Seattle taking the first step toward increasing its minimum wage. Residential and commercial demand is so strong in the city these days that Seattle may have more latitude than its suburbs to boost its minimum wage significantly without encountering negative employment effects. And maybe the city needs to move first in order to convince its neighbors (and itself) that a $15/hour minimum wage won’t make the sky fall.

But these statistics offer an important reminder that the problems of low wages, inequality, and social mobility do not stop at city borders. Ultimately, more cities might try acting in coordination with their surrounding jurisdictions, as the District of Columbia did with two Maryland counties, to boost their minimum wages and ameliorate any “border effects.” And as Seattle contemplates other key policy initiatives, like universal preschool and backfilling state cuts to transit funding (a King County ballot initiative failed last month), it should keep open the lines of communication with its neighbors, and act as one county—or region—where it can.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Seattle, Its Suburbs, and $15/Hour

May 12, 2014