Relationships are a central feature of human existence. “Man is by nature a social animal” observed Aristotle twenty-four centuries ago. “An individual who is unsocial naturally and not accidentally is either beneath our notice or more than human.” Our relationships with children, parents, partners, and friends define and give shape to our lives. But relationships beyond kith and kin—with colleagues, fellow congregation members, neighbors, and associates—can also be important sources of both pleasure and support. Relationships are the sinews of human society, connecting individuals to a larger whole. They are an important element of “social capital,” defined by Harvard scholar Robert Putnam as “the collective value of all ‘social networks’ and the inclinations that arise from these networks to do things for each other.”

Help provided by a non-family member relationship is a leitmotif of American culture. In story after story, a coach or preacher provides vital support to a disadvantaged teenager or young adult. Indeed, “coach” occupies a semi-mythological status. Next week sees the publication of an important new book, from Putnam, Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, describing the “opportunity gap” resulting in part from disparities in access to social capital in different communities. The title was not chosen lightly. By stressing “our kids,” Putman points to our collective responsibility to the next generation and the need to extend our relationships of care and support.

Relationships with non-kin are often formalized through mentoring and play a significant role in US society. There are around 5,000 mentoring programs helping about three million young people, with the largest—Big Brothers Big Sisters—serving almost 200 thousand, according to a review by Phillip Levine for the Hamilton Project at Brookings. But there is a paucity of evidence for the effectiveness of these programs. Initiatives based outside the school walls appear to have the most impact, but there is not enough evidence to suggest that public investment would be justified on a cost-benefit basis, Levine concludes.

MENTORING RELATIONSHIPS: A NEW DATA SOURCE

One of the problems with research in this area has been the absence of data on any significant scale. Mentoring programs have been assessed on a case-by-case basis. Studies of social capital have typically focused on specific communities, or relied on proxies, such as levels of trust or institutional affiliations.

But a new source of data has just become available, in the form of a module on the Panel Survey of Income Dynamics (PSID). Between May 2014 and January 2015, four questions were asked of 13,042 respondents in an attempt to glean information on helping relationships during adolescence and early adulthood:

When you were between the ages of 17 and 30:

- …was there a family member other than (your mother/your stepmother/the woman who raised you) (and) (your father/your stepfather/the man who raised you) who provided you with positive support or mentoring that helped you succeed in your work life?

- …was there a family member other than (your mother/your stepmother/the woman who raised you) (and) (your father/your stepfather/the man who raised you) who provided you with positive support or mentoring that helped you succeed in your interpersonal relationships, such as marriage or a marriage-like relationship?

- …was there an adult outside of your family who provided you with positive support or mentoring that helped you succeed in your work life?

- …was there an adult outside of your family who provided you with positive support or mentoring that helped you succeed in your interpersonal relationships, such as marriage or a marriage-like relationship?

We analyze the data produced by these questions in an attempt to answer the following question: Are there differences in reported rates of helping relationships between different groups? We narrow our sample to include only those over the age of 30 in 2011, since the questions use up to the age of 30 as the period during which respondents are asked to report helping relationships. Our final sample includes 6,117 individuals.

There are clear limitations with the data generated by the new PSID questions. First, the questions are backward-looking, relying on the recall of the respondent. Second, there may be differences between people in how they define key terms, including what constitutes positive support, mentoring, and success. Third, there may be individual attributes that are related with both the likelihood of recalling a helping relationship and another variable, such as education. Fourth, since the age of respondents varies, there is corresponding variation in how far back they are being asked to remember.

Despite these caveats, the PSID offers an opportunity to examine self-reported helping relationships from a large-scale nationally representative dataset.

MENTORING RELATIONSHIPS: ON THE RISE?

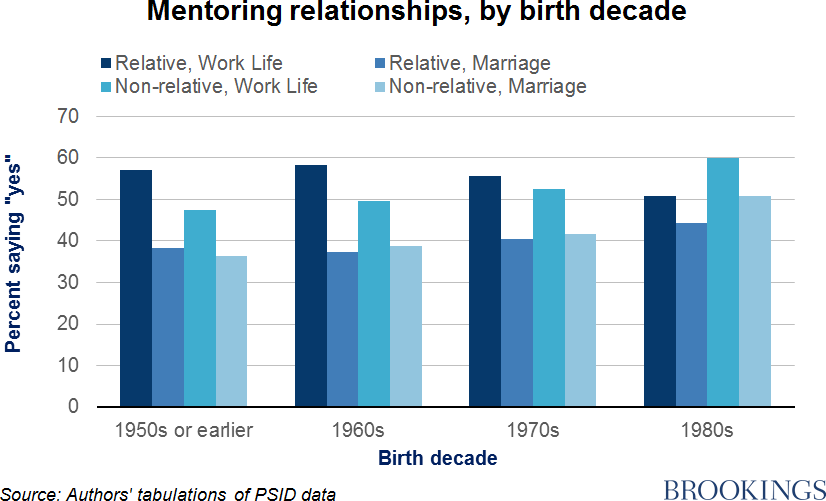

Except among the youngest cohort, fewer than half of Americans report getting help with work or marriage from either kin or non-kin. Comparing the most recent cohort (born in the 1980s) with older cohorts, the main trends appear to be a reduction in help from family with work, which is more than matched by an increase in help from non-family members, and a slight rise in reports of helping relationships with regard to marriage:

MENTORING RELATIONSHIPS: GENDER

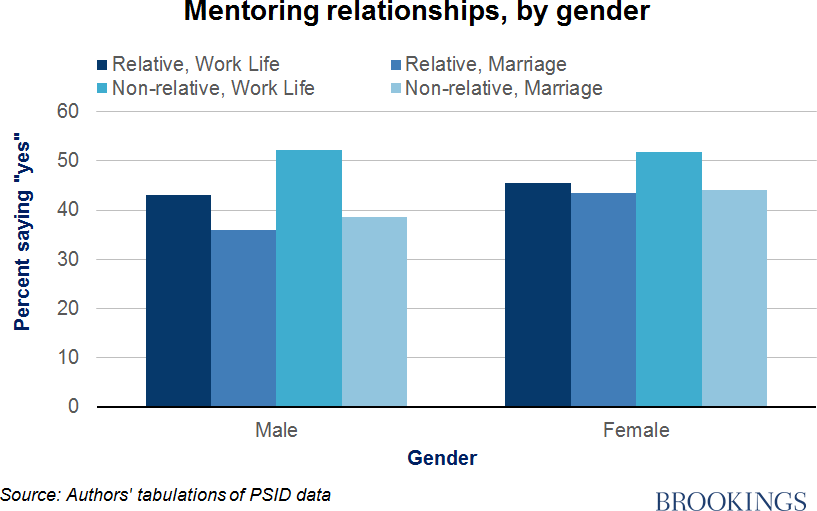

Women are significantly more likely to report mentoring relationships than men, for both marriage and work from family members and for marriages from non-family helpers. Men only match women in reports of help from non-kin with their work life:

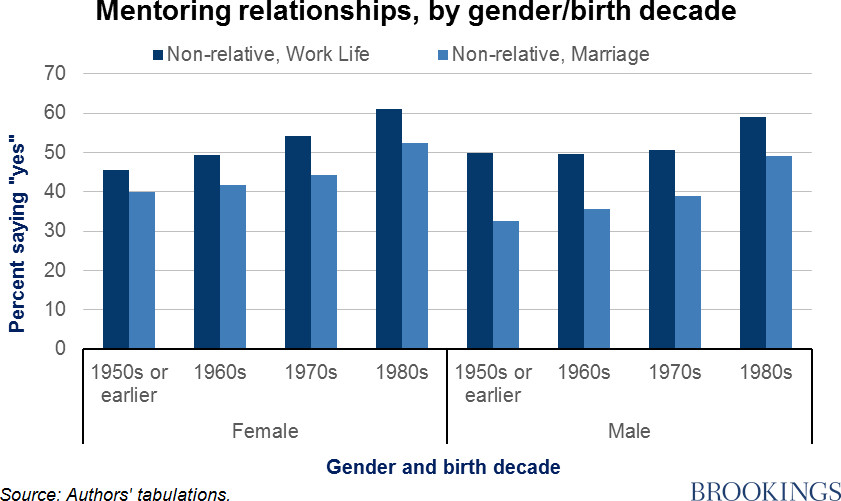

Younger cohorts of both men and women report more mentoring relationships with non-kin. The biggest increases for women are for help with work, rising from 45 percent for respondents in their 60s (and beyond) to 61 percent for those in their 30s. For men, the biggest increase is in receiving help from non-kin with their marriage (32 percent to 49 percent):

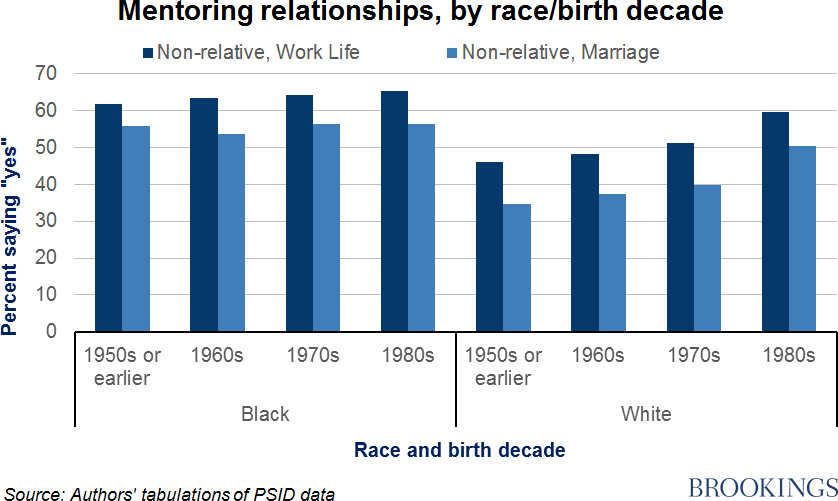

MENTORING RELATIONSHIPS: RACE

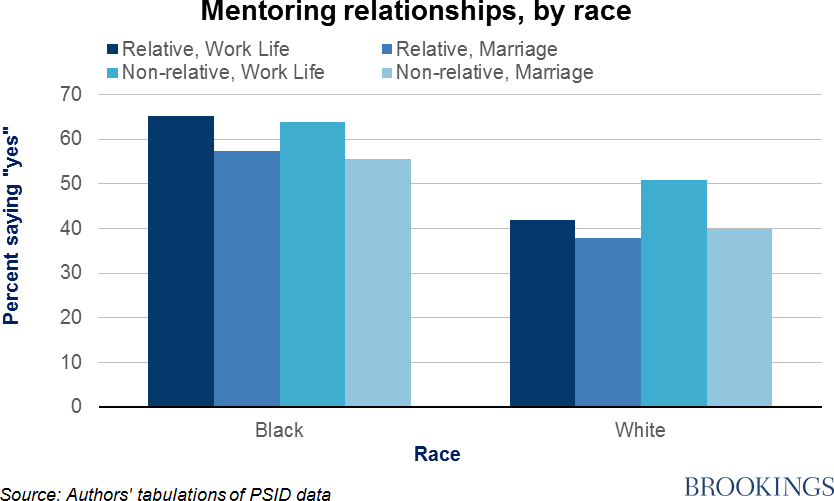

Black respondents are more likely to report mentoring relationships than whites and other races[i], for both marriage and work and from both family and non-family helpers:

Black Americans report fairly stable and high rates of mentorship over time. Younger age cohorts of White Americans, however, are more likely to report having received help, which may reflect a rise in mentoring relationships, a heightened awareness of these relationships, or a greater ease of remembering them if they were more recent:

But whatever the explanation for the rise, it does not appear to alter the picture on race: black Americans of all ages are more likely than whites to report being helped.

Any interpretations of these results have to be treated with extreme caution, given the limitations of the data. Perhaps black and female respondents have needed more mentoring relationships, given their historically weaker socioeconomic position. Perhaps they simply remember the relationships more vividly or are more likely to report them. Perhaps women are more willing to seek out help. Perhaps the black community has developed stronger support networks in the fact of explicit and implicit racism and discrimination. These are all questions for further inquiry.

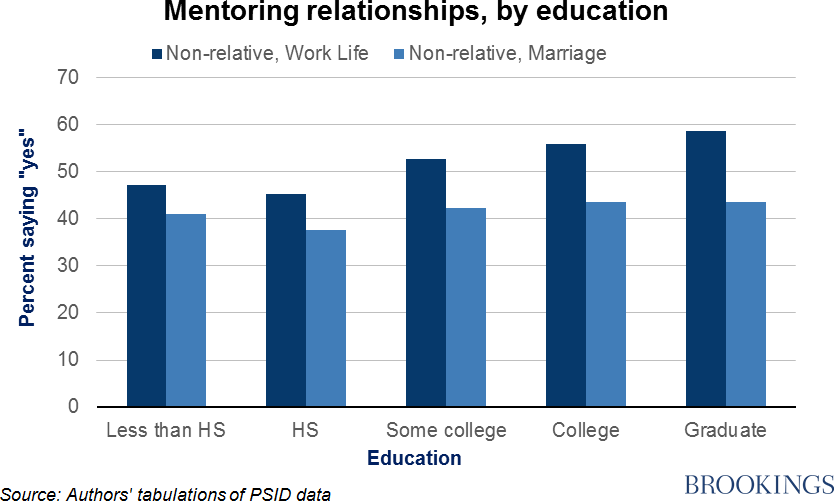

MENTORING RELATIONSHIPS: EDUCATION

Those with higher educational achievement are more likely to report having a mentoring relationship, especially from non-kin and with regard to work:

Of course, we cannot say anything here about direction of causality. Those who are helped may go on to higher levels of education; equally, higher levels of education may widen the possibilities for finding mentoring relationships.

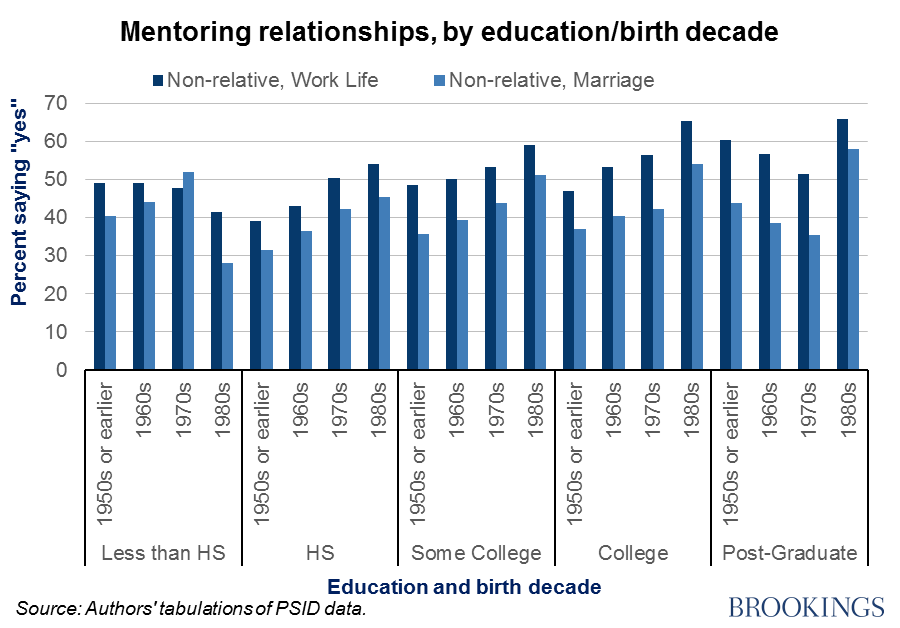

Reports of mentoring relationships with non-kin, with regard to both work and marriage, are higher in the younger age cohorts at every education level, with the exception of high school dropouts:

HELPING OUT: RELATIONSHIPS AND EQUALITY

Our analysis of the new PSID dataset raises questions rather than providing answers. While there are clear and significant differences in reports of mentoring relationships by gender, race, and education level, the interpretation of these results is necessarily difficult.

Most of us need help at various points in our life, and many of us are fortunate enough to receive it. Empirically defining, capturing, and weighing the value of relationships is extremely difficult, as even this initial analysis demonstrates. We all know these relationships to be valuable indeed, not least in helping us both to seize opportunities and to overcome setbacks that life sends our way. But, it is useful to supplement what has largely been a qualitative research field with some quantitative data, in order to generate new questions and perhaps challenge assumptions based on anecdote.

[i] Asian respondents are least likely to report receiving any type of mentoring. American Indian and Alaska Native respondents consistently report higher rates of mentoring than do white respondents but lower rates than do black respondents. We omit detailed results on other races due to small sample sizes.