The connection between single motherhood and social mobility has been a hot topic since last year’s landmark study on economic mobility from Raj Chetty and his colleagues at the Equality of Opportunity Project. That study showed a strong relationship between high levels of single motherhood in a region and low rates of upward mobility. (Of course, Belle Sawhill and Ron Haskins have been saying something similar for years…)

Single Mothers and Mobility

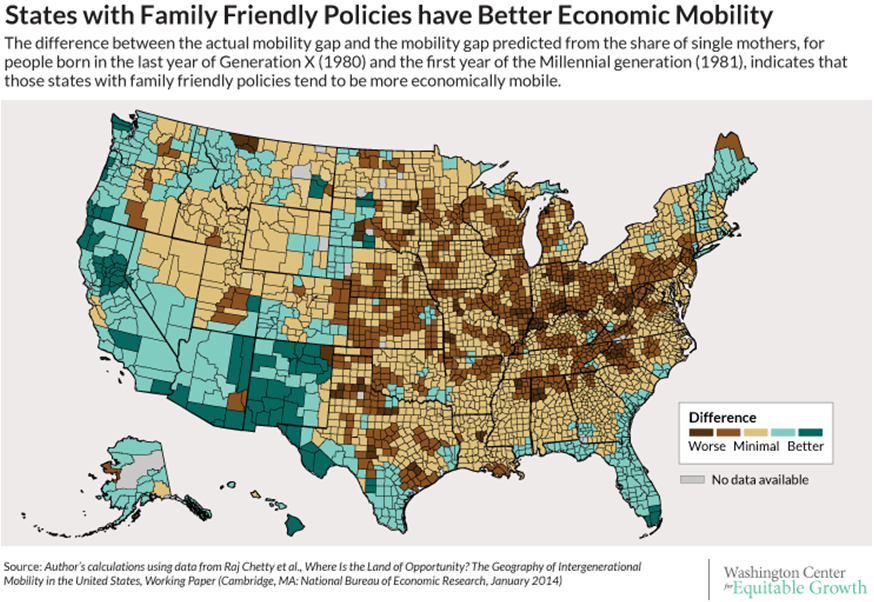

Now a new paper from Carter Price at the Washington Center for Equitable Growth takes the debate a step further, by asking whether more support policies for families helps reduce the impact of single parenthood on mobility. First, Price looks whether the mobility gap in particular localities is higher, lower, or about what would be expected, given the share of single mothers in an area:

Some states have higher levels of mobility than their rates of single motherhood would suggest and vice versa, indicating that a third variable might be driving this association. The suggestion from the WCEG is that this variable could be family-friendly public policies.

Do Pro-Family States Have Higher Mobility Rates?

The paper highlights 13 states – California, Connecticut, DC, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Washington, and Wisconsin—which have had longstanding family-friendly policies. Price’s thesis rests on the fact that six of these states (California, Washington, Oregon, Rhode Island, Maine, and Vermont) are more mobile than their levels of single motherhood would predict

OK. But what about the other seven “family-friendly” states? Four of them (New Jersey, Minnesota, Tennessee, and Wisconsin) fall squarely in the “dark brown” region of the map, meaning that they have less mobility than predicted by their rates of single motherhood. The remaining three have rates of mobility close to those predicted by rates of single motherhood. Price admits that his conclusions aren’t definitive, but it does seem an oversight not to address the states with family friendly policies that do not support the broader argument. New Jersey is a particularly surprising exclusion, since it is one of only three states that provides paid family leave. Moreover, why do states like Florida, Arizona, and New Mexico have higher mobility than one would expect, even though they are low in terms of family-friendly policies?

Careful!

This is not to say that family-friendly policies do not influence economic mobility. Last week, we wrote about a recent article in Future of Children which highlights the importance of paid family leave and workplace flexibility for early child development. But researchers need to follow Chetty’s example and be careful about drawing causal conclusions. We second the call made at the end of the WCEG piece, addressed to those arguing for marriage-friendly policies, and urge that it also be applied to the call for more family friendly policies: “It is important for researchers to do more than just a cursory analysis of these data and to understand the mechanisms of mobility before making strong policy recommendations.”

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Do Family-Friendly Policies Boost Social Mobility?

June 12, 2014