Editors’ Note: Timmons Roberts and the students in his Climate and Development Lab at the Institute at Brown for Environment and Society, attended the negotiations in Paris.

Over the course of two weeks, we tracked electronic media coverage of the Paris climate talks—and its absence – in the four highest-circulation print news sources in the U.S.: The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, the Los Angeles Times, and USA Today. Together, they published a total of 424 articles on the climate change conference—a remarkable number. But not all of that coverage was instructive, and many key issues in the negotiations were scarcely mentioned. Citizens informed by the U.S. print media gained only a partial understanding of the issues at the core of the climate change negotiations.

Reuters/Jacky Naegelen – Journalists work in the press room during the opening day of the World Climate Change Conference 2015 at Le Bourget, near Paris, France, November 30, 2015

Quality press coverage of the UN climate negotiations is crucial for the public to understand what was at stake in Paris and what was accomplished. What were negotiators actually arguing over? What did they decide? Is the final document as important as the politicians assembled in Paris said it was?

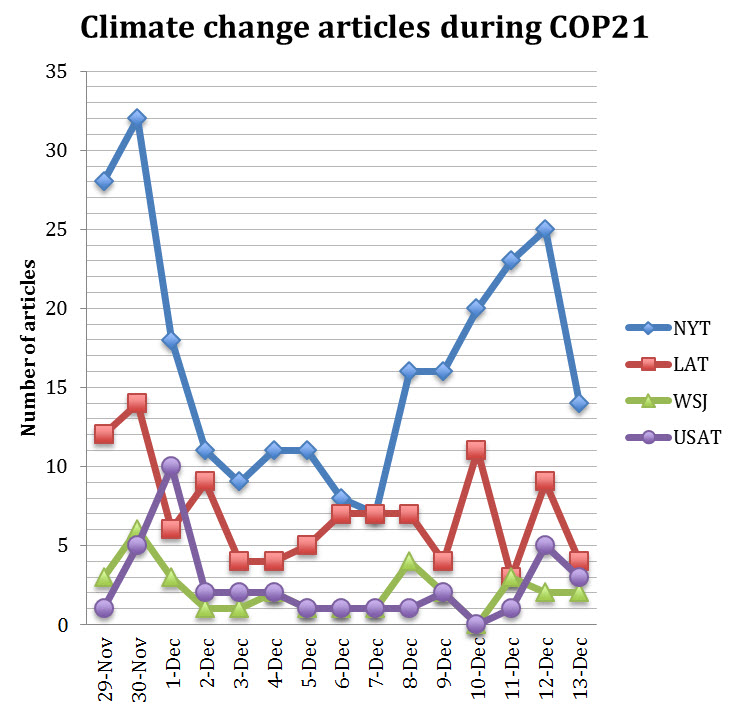

Who covered the talks most

The New York Times towered over the others in its overall coverage, with a total of 249 articles related to the conference during the span of just a week. It was followed by the Los Angeles Times with 106 articles (less than half as many), and then USA Today and The Wall Street Journal with 37 and 32 articles, respectively (approximately one-seventh and one-eighth the number of The New York Times).

To put these numbers into context, we compared them to mentions of “ISIS” in each of these four papers on November 14 and 15—the two days following the attacks in Paris. During those two days, The Wall Street Journal and USA Today ran an average of 10 and 18 articles per day on ISIS, respectively, yet on climate change each had a daily average of only two articles. By contrast, The New York Times and Los Angeles Times had quite similar numbers between ISIS post-Paris attacks and their U.N. negotiations averages.

Over the span of the two weeks from Sunday, November 29 to Sunday, December 13, newspapers had the greatest coverage of the talks at the beginning and at the end. During the first three days of the conference, they collectively published an average of 46 articles per day. During the last three days of the conference (December 10-12), the four papers averaged 34 articles per day. During the three days in the middle of the two weeks (Dec. 5-7), coverage dropped to an average of 17 articles per day. In other words, when the pomp went away, so did the coverage—just as the negotiations got going in earnest. And coverage did not pick up again until there was something easily graspable to report on at the end of week two.

FIGURE 1

Source: Authors’ calculations.

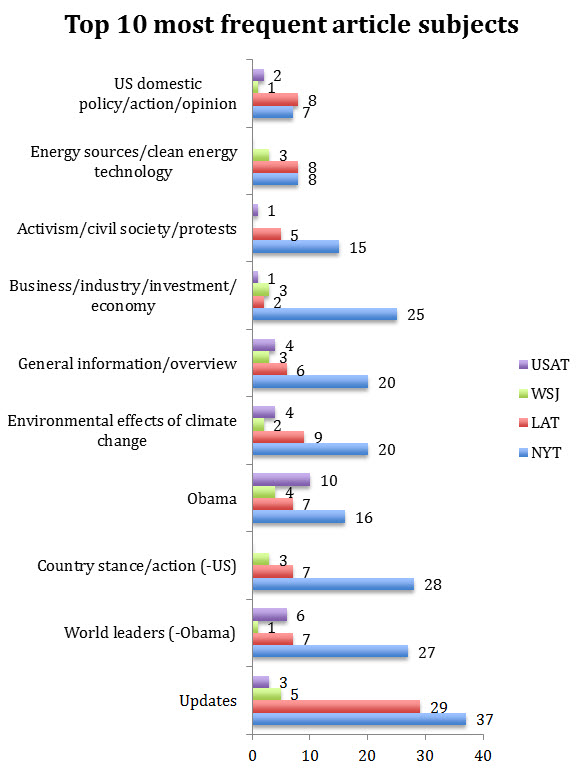

What they wrote about

Climate change is a complex subject—one the media has largely struggled to adequately report on in the past—and these negotiations were no exception. Understanding what happened on certain key topics requires background knowledge that may be hard to convey in a short article. The conference was a slow process carried out over two weeks, rather than a singular event that could be encompassed easily in a single article. While the rallies across the globe and the speeches by world leaders at the start of the talks were easier to cover, the middle and latter portions of the conference were more complicated.

To compensate, many journalists chose to focus on specific countries or people—world leaders such as President Barack Obama, celebrities such as Bill Gates—and the particular things they said or actions they took. Others tried to capture attention by linking their reporting to relevant world news, such as the Syrian refugee crisis or the terrorist attacks in Paris. Still other writers framed the negotiations as having a central conflict—identifying the biggest sticking points or disputes between countries and leaders. These approaches followed common journalistic norms of focusing on individuals and the conflict between them, leading to a somewhat piecemeal representation of the conference.

As a result, most articles did not focus on the major issues being discussed in Paris. They gave broad updates on the progress of the negotiations, the speeches and positions of President Obama and other major world leaders, and the actions or stances of other leading nations. In addition, they discussed the environmental effects of climate change, of which the greatest number focused on air pollution in India and China. Still others relayed general information about the talks, or focused on business, civil society, energy sources or clean energy technology, and U.S. domestic policy.

Many of the main issues underlying the negotiations were not covered in depth. In particular, some of the key issues to be resolved at the conference revolved around the world’s least-developed nations—those that are considered to be the most vulnerable to the early impacts of climate change due to their lower levels of economic development, conflict, and poverty, yet have done little to contribute to the problem. Of articles about other nations and world leaders outside the U.S., 35 focused on individual developed countries and 23 were about major emerging economies (India, China, and Brazil), while only seven articles discussed Africa and other groups of developing countries. No leaders from these areas were mentioned.

FIGURE 2

Source: Authors’ calculations.

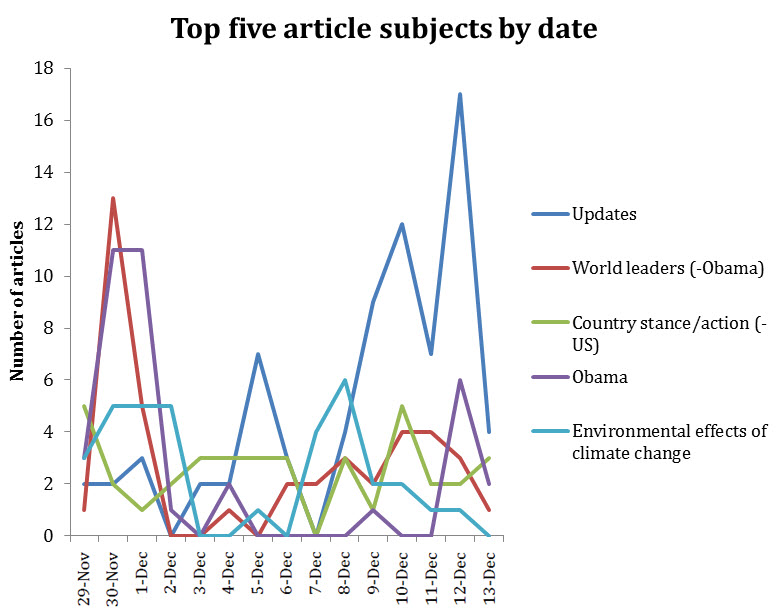

The subject matter that articles addressed shifted as the week went on. Coverage of the first day reflected civil society activism during the worldwide day of action that coincided with the kickoff to the conference. Articles on the second day focused on President Obama and the record-breaking number of world leaders gathered in Paris to give speeches. After that, coverage drifted, with many articles only tangentially related to the talks themselves and instead focusing on various other subjects related to climate change, with just a line or two mentioning that the talks were going on. It wasn’t until the conference drew to a close that the press re-focused on the progress of the talks, especially as a draft text was released on December 10and an agreement reached on the 12.

FIGURE 3

Source: Authors’ calculations.

The stories not told

Looking across the 424 articles, some of the core issues at stake in the negotiations were missing or downplayed. These included:

- the allocation of responsibility between developed and developing countries (five articles)

- the social and human rights issues related to the effects of climate change (13 articles)

- the contentious issue of helping those facing irreparable loss and damage from climate change (one article)

- the transparent reporting of the billions of dollars of climate finance flowing from the global North to the South (three articles).

The climate negotiations hinged upon issues like these, yet while they were mentioned, they were treated as side issues in most articles

This is a shame, because coverage of the conference sets the stage for public understanding of what was accomplished in Paris and what matters in the coming years. While reporters made valiant efforts to chronicle the climate change negotiations, the average reader came away from the talks with a piecemeal understanding dominated by a few big names and little in-depth knowledge of many of the main issues the conference attempted to address. Citizens informed by the U.S. print media will have a partial, and quite inadequate, understanding of the issues at the core of the climate change negotiations. They will know there was an agreement, but won’t really know what it entails, where it falls short, or why they should care. Given the transformation needed in American society away from fossil fuels and energy waste, this was a lost opportunity for education about the tough issues raised by this existential crisis.

Read more by Roberts in the new book “

Power in a Warming World: The New Global Politics of Climate Change and the Remaking of Environmental Inequality

,” published by MIT Press.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Paris climate talks according to U.S. print media: Plenty of heat, but not so much light

December 18, 2015