As Donald Trump marches towards the Republican nomination, speculations about the alternatives are intense. As we’ve written before, a brokered convention, denying Trump the nomination at the eleventh hour, seems like a real possibility. But one alternative could begin before the convention rolls around: an independent bid for the presidency—by Trump or by someone else.

The conventional wisdom has been that it’s too late for an independent to get into the race; that the ballot access provisions essentially mean that an independent candidate for president has to start very early. But in a Wall Street Journal column, my colleague Bill Galston has upended some of the conventional wisdom. Galston is an authoritative source on this question—in 1980, he worked for the independent candidacy of John Anderson. The Anderson team started in April, and with a lot less money than Trump or Bloomberg would have. Despite this, they managed to get Anderson on the ballot in all fifty states. Moreover, in the course of doing so they took Ohio to court for overly restrictive ballot access laws. In a case that still holds today, the Supreme Court in Anderson v. Celebrezze (then the Ohio Secretary of State) held that Ohio’s early deadline violated the First Amendment’s guarantee of freedom of association. Galston goes on to write: “Anderson v. Celebreeze remains good law today, and it has had an impact. As Mr. Winger [Richard Winger, Publisher of Ballot Access News] notes, lower courts have used it to strike down June filing deadlines in five states—Alaska, Nevada, South Dakota, Arizona, and Kansas.”

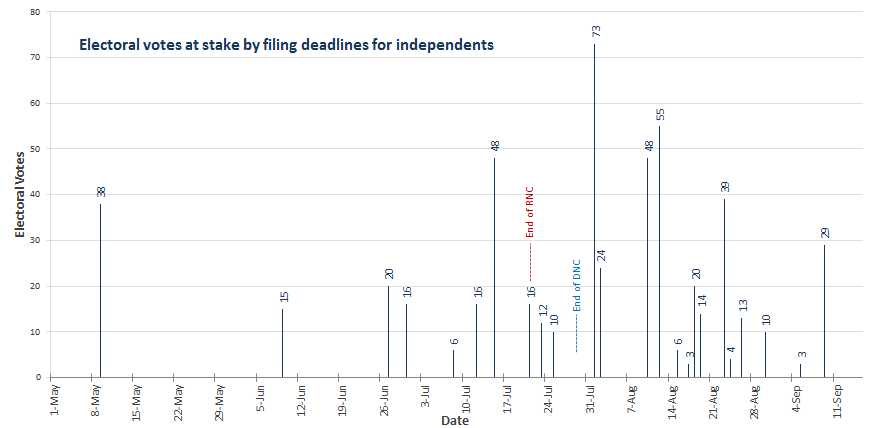

So what obstacle does an independent candidate face getting on the ballot? We broke this down into two charts. The first one shows the number of electoral votes at stake on each day there is a filing deadline. The earliest one is Texas with a May 9 deadline. Were a candidate to miss this deadline they could forfeit the chance of winning Texas’ 38 electoral votes. The real difficulty with the calendar, however, is that if a candidate were to wait until the end of the Republican National Convention to decide to run as an independent, he would forfeit 175 electoral votes, and if a candidate were to wait until the end of the Democratic National Convention, he would forfeit 197 electoral votes. Deciding to run in reaction to a national convention outcome could easily restrict ballot access even further, as late deciders would be right up against a slew of filing deadlines that begin in late July and August.

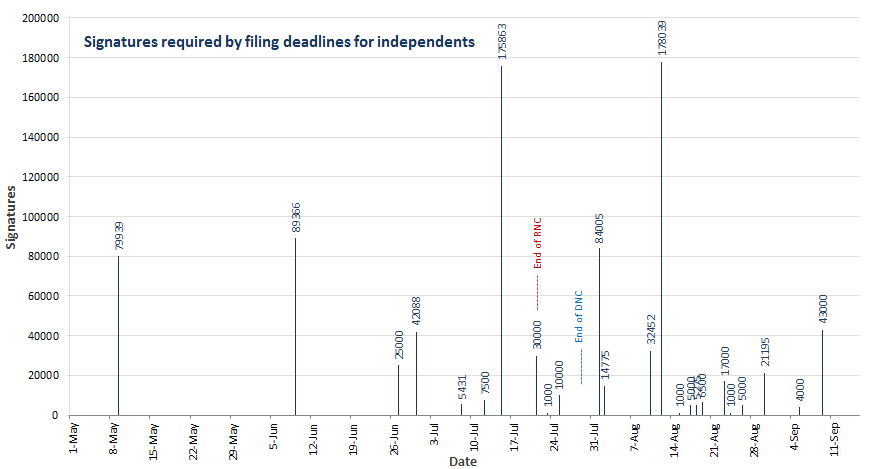

Assuming, however, that a candidate does decide to get in the race as an independent, what do they have to do? They have to collect signatures from voters. Thanks to John Anderson’s independent candidacy over thirty years ago, these state by state requirements are not terribly onerous. But taken together, they present a challenge to a late starter. The greater problem an independent candidate will have is that whichever of the two main political parties believes they stand to lose votes from the independent candidacy will mount an intense legal campaign to challenge each and every signature the independent candidate collects in an attempt to throw the candidate off the ballot.

This means, as Bill Galston points out, “…there is a delicate timing issue.” Galston continues, “Right now is not too late to mount an independent candidacy, but it will be when the Republican Convention convenes in late July. So this venture would have to be launched well before the identity of the party’s nominee is known.”

An independent candidacy for president is not out of the question after all. But whoever is thinking about it needs to get started—yesterday.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How late is too late to mount an independent bid for the presidency?

March 23, 2016