Editor’s Note: This blog post is part of The Primaries Project series, where veteran political journalists Jill Lawrence and Walter Shapiro, along with scholars in Governance Studies, examine the congressional primaries and ask what they reveal about the future of each political party and the future of American politics.

In more than 200 years of American history, two things have been true about our politics. One, Americans really hate the whole idea of political parties and they proudly tell friends and pollsters that they vote “for the person, not the party.” And two, the best predictor of a person’s vote is their political party. In spite of what they say, most Americans identify with one party or the other most of the time and they vote for their party with an amazing degree of consistency. Lots of ink has been spilled trying to figure out how these two things exist simultaneously, as well as the related question of why we don’t have a third party – which many Americans seem to want but which never happens. The reasons are complex but they go to an issue we’ve been studying here at Brookings in “The Primaries Project” – the factions within each of the major American parties.

The two American political parties are, as the saying goes, “big tents.” They have to be. The underlying structure of the American system, winner-take-all rules for the election of House members, Senators and President (through the Electoral College) means that coming in second, let alone third or fourth, is meaningless in terms of governing. This is not the case for democratic systems in other countries that use proportional rules. There, small parties can win enough to become, from time to time, part of the governing coalition where they can prove their worth and perhaps grow. Proportional systems can also incentivize third parties to remain in existence because they have a good chance of consistently having seats in the legislature.

In a winner-take-all system third parties are simply spoilers, which is why they rarely last for more than a few election cycles and then, their issues and voters are subsumed into one or the other major party. But the persistence of two-party government doesn’t mean that change is absent. Change happens continually; you just have to look within each political party. In the years following the Civil War the Republican Party, while dominant, was in a continual internal battle between “Mugwumps”, “stalwarts”, and “half-breeds.” By the turn of the century they were challenged by Progressives and later, in the 1950s, by “New Right” Republicans. The Tea Party movement stands in a long line of internal challenges to whoever held the reins of power within the Republican Party.

Ditto for the Democrats who were, after all, the party of segregation after the Civil War and subsequently turned into the populist, “cross of gold” party at the end of the nineteenth century. Their transformation into the party of civil rights, women’s rights and then New Democrats was the result of a series of internal factional battles.

In modern American politics, the place to see why and how parties change is the primaries and that is why we set out, six months ago, to study not just the “hot” congressional primaries but every Congressional primary where there was a contest—even if the challenger was not likely to win. We sought to learn more about the factional divisions within each party. In this first ever comprehensive look at parties, my co-author Alex Podkul and I looked at all 1,662 candidates in the 2014 primaries and coded them, as to their position within each party, based on their website. This exact same thing could have been done at any point in the past two hundred or so years except that in the old days internal party battles took place away from the public eye. Primaries are pretty new to the American political scene. For most of our history, contests between factions over who would be the party’s standard bearer and what issues they would represent, took place in the proverbial smoke filled rooms of State Party conventions.

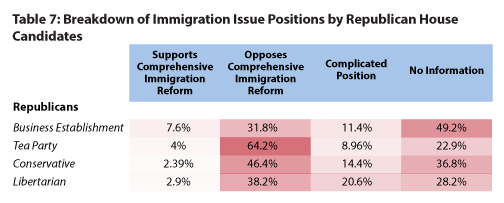

Factions drive ideas within the political parties. And that’s what our analysis of 2014 illustrates. For instance, have a look at the division within the factions of the Republican Party on immigration. While nearly every Republican who talked about immigration was opposed to comprehensive immigration reform, 41% of the Republican candidates ignored it. Of those who did discuss the issue, it was clearly more important to the Tea Party than to other segments of the Republican Party. Clearly the Tea Party faction will continue to try and prevent immigration reform.

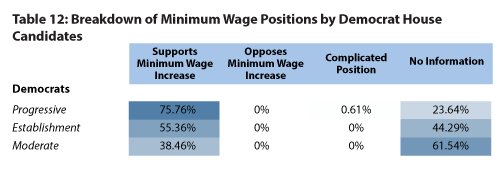

On the Democratic side nearly half of all candidates said nothing about raising the minimum wage but of those who did it is clear from the following table that self-identified “progressive” Democrats are driving this issue within the party.

In a two party system, buttressed by a winner-take-all electoral system, change happens as one or the other political party morphs into something else as a result of its own internal factional wars. Today, in a Brookings forum we’ll be exploring the internal makeup of the two major parties and what that tells us about the future of American politics.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

The Primaries Project: Understanding American Parties and Factions

September 30, 2014