People often immigrate to a new country to seek a better life for their children. In their new country, immigrant children very often show rapid upward mobility. But immigrants are very far from being a homogenous group, arriving with very different levels of education, skills, and economic resources. So how are the children of one particular group—Hispanic immigrants—doing? The answer to that question hinges on the point of comparison.

Hispanic children fare quite badly in the U.S. compared to other Americans

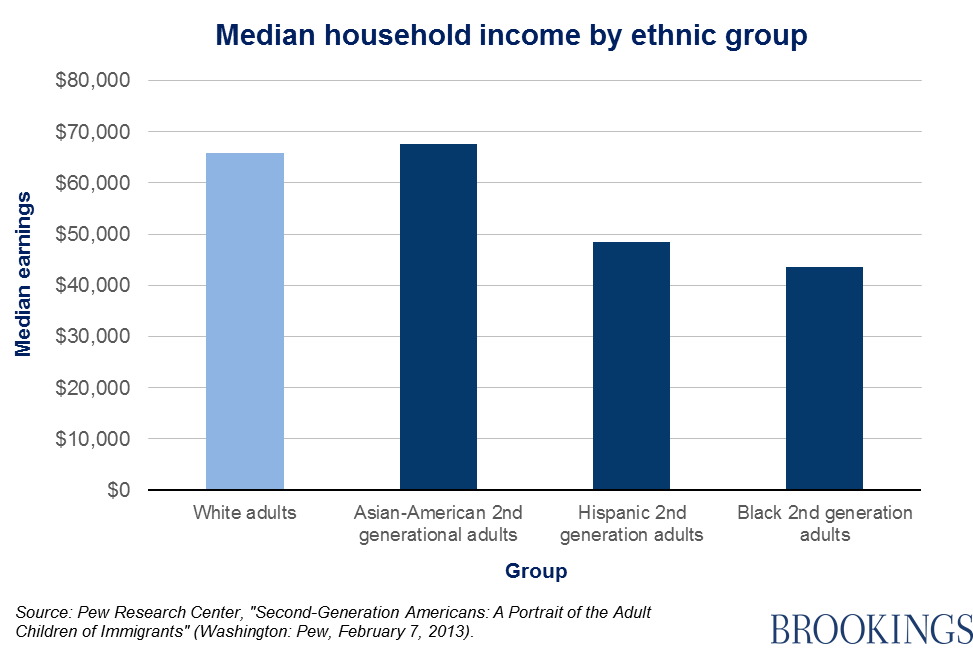

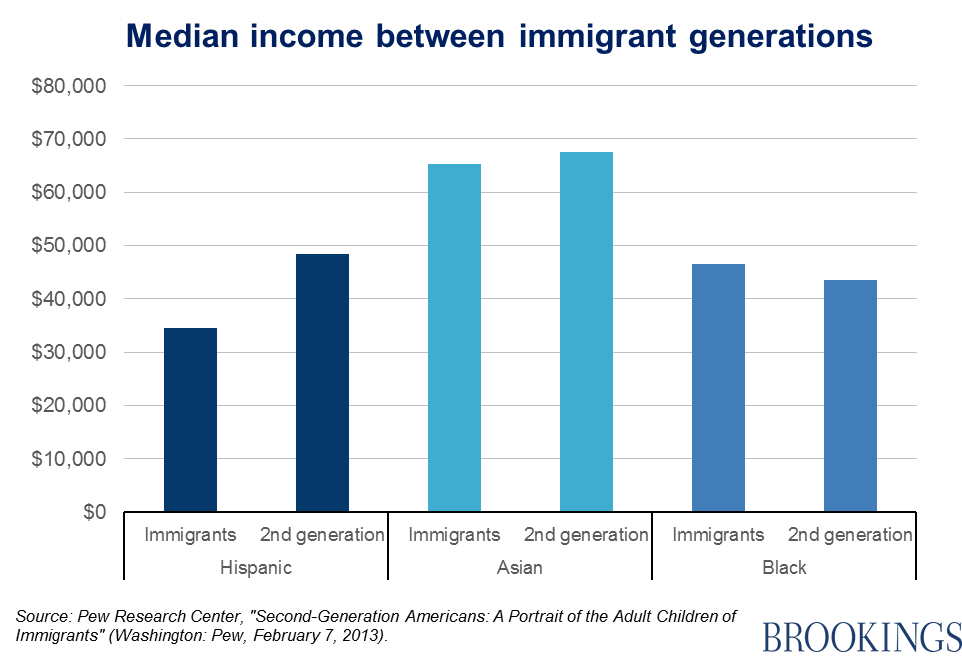

One way to look at how second-generation immigrants are faring is to compare them to other groups in the U.S., including whites. Through this lens a familiar picture can be seen. Hispanic Americans, along with African Americans, have lower median earnings than both whites and second-generation Asian Americans:

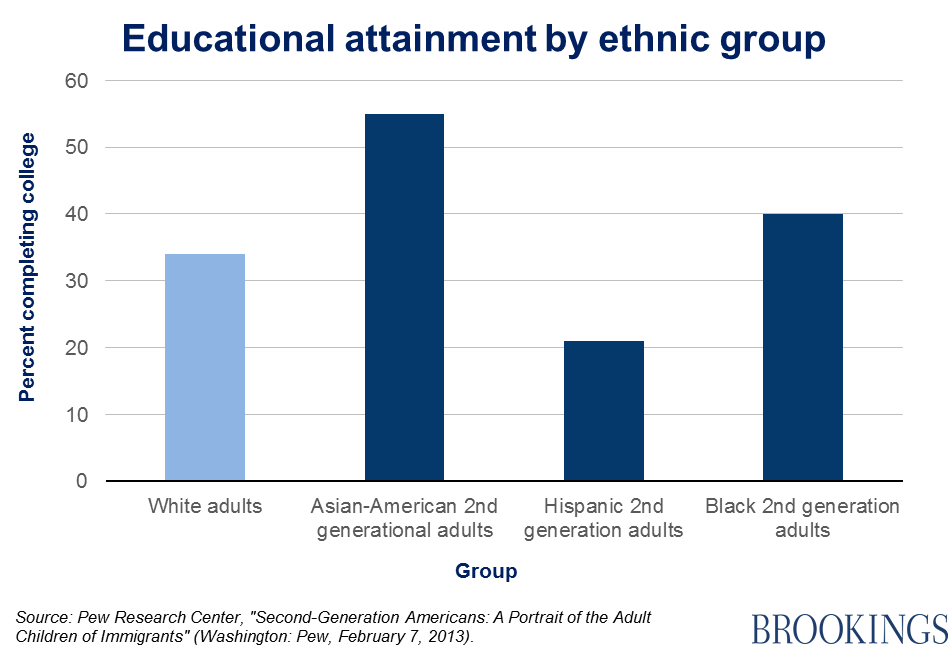

College completion rates are also lower for 2nd generation Hispanic immigrants compared to their white peers, as data from the Pew Research Center shows:

Even more surprising is that the children of black immigrants are doing well in terms of college completion rates—twice as well as the children of Hispanics, and better, in fact, than among the general population of whites.

What if their parents hadn’t come to the U.S.?

Another way to look at the position of second-generation immigrants is by comparing them not to their fellow citizens in the U.S. but to their likely outcomes had they stayed in the country their parents left. They may not be better off that the average American, but they may be a lot better off than they would have been in the ‘old country.’

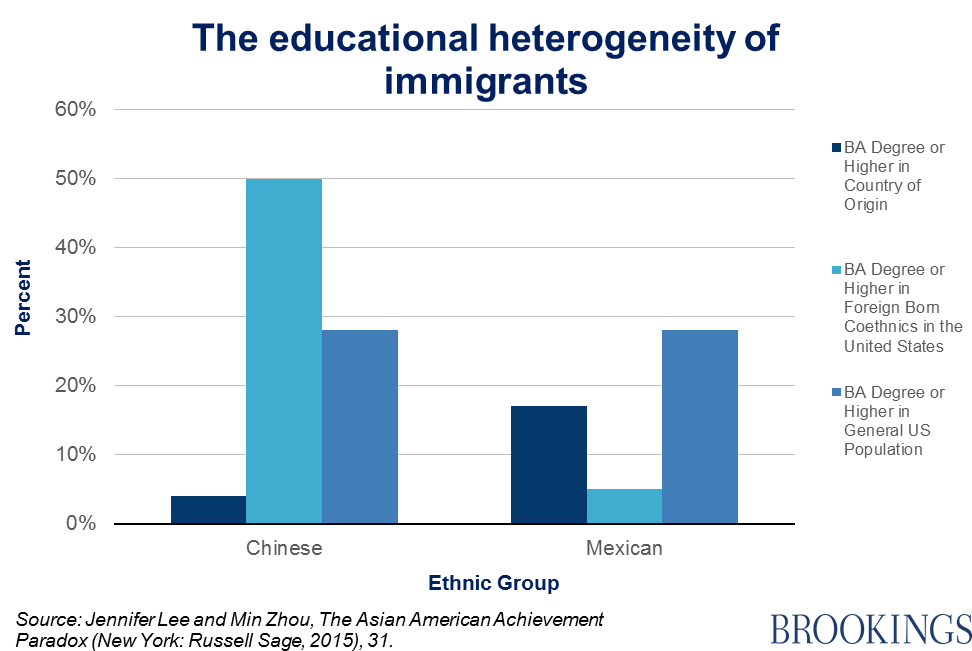

This is obviously a more difficult comparison, especially considering the extreme heterogeneity of the immigrant population. Some immigrant groups are better educated than those in their home country, and even the general U.S. population. This ‘hyper-selectivity’ is a feature of many Asian-American groups including the Chinese (as a recent book by Jennifer Lee and Min Zhou, The Asian American Achievement Paradox, shows).

At the other extreme, not only do some immigrants have less education than the U.S. general population, but also less than the population they left. This ‘hypo-selectivity’ describes Mexican immigrants:

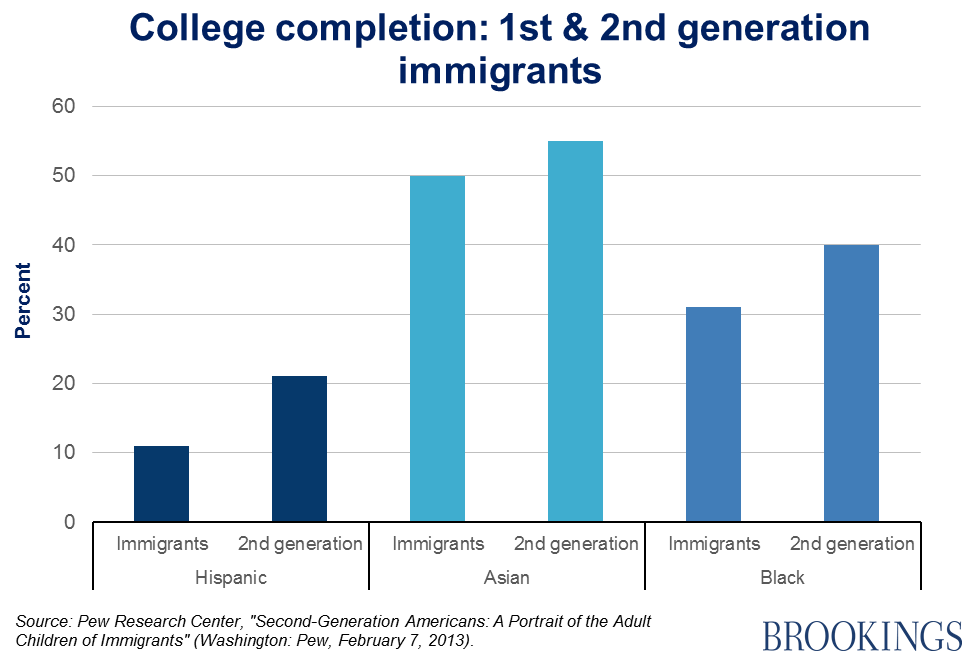

In terms of the education race in the U.S., then, Mexican immigrants start out a long way behind. The children of poorly educated adults are much less likely to end up highly educated themselves. Simply comparing the situation of Mexican and other Hispanic groups with the general population, or with very different immigrant groups, risks missing the very significant gains that have been made between first and second generations in terms of both education and income:

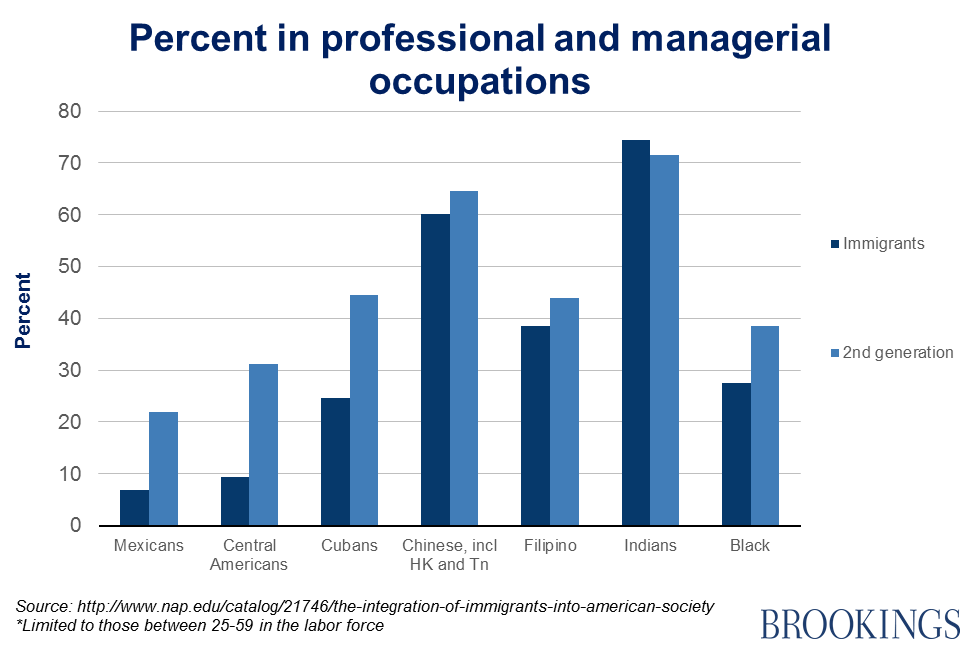

A report on the integration of immigrants into American society released this year shows that not only do second-generation Hispanics do better than their parents educationally and in terms of household income, but they also make gains in terms of occupational status. Many have left the agricultural work their parents performed, with 22 percent of second-generation men from Mexico and 31 percent of those from Central America in professional or managerial positions in 2003-2013.

The children of Hispanic immigrants have climbed further than children from other ethnic groups, compared to their starting point. None of this is to say that we should not strive to close the wide gaps in outcomes between different racial and ethnic groups. But we should not naively compare immigrant groups with radically different backgrounds, or dismiss the huge strides already made by American Hispanics.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How upwardly mobile are Hispanic children? Depends how you look at it.

November 10, 2015