Like Ulysses tying himself to the mast, policy-makers can use policy commitment devices to avoid short-term political temptation and steer policy to achieve long-term goals. In my recent paper, Ulysses goes to Washington: Political myopia and policy commitment devices, I discuss three such devices: institutions, goals, and advice. The Federal Reserve and the Defense Policy Board Advisory Committee each show how federal institutions and committees can help keep policy on a longer-term footing.

Goals as commitment devices

But simply setting a goal for policy can act as a commitment device too, if certain conditions are met:

- Prominence: Public commitments are harder to break.

- Specificity and Simplicity: Clear goals with concrete timelines are more binding.

- Bipartisanship: Goals have to survive political transitions.

- Tracking and Accountability: Independent bodies hold the government accountable.

“Abolish child poverty”: Lessons from the U.K.

The U.K. poverty target demonstrates the value of a commitment device. In 1999, Prime Minister Tony Blair made a high-profile pledge to halve child poverty by 2010 and abolish it by 2020. In 2010, the goal was enshrined in law, with all-party political support.

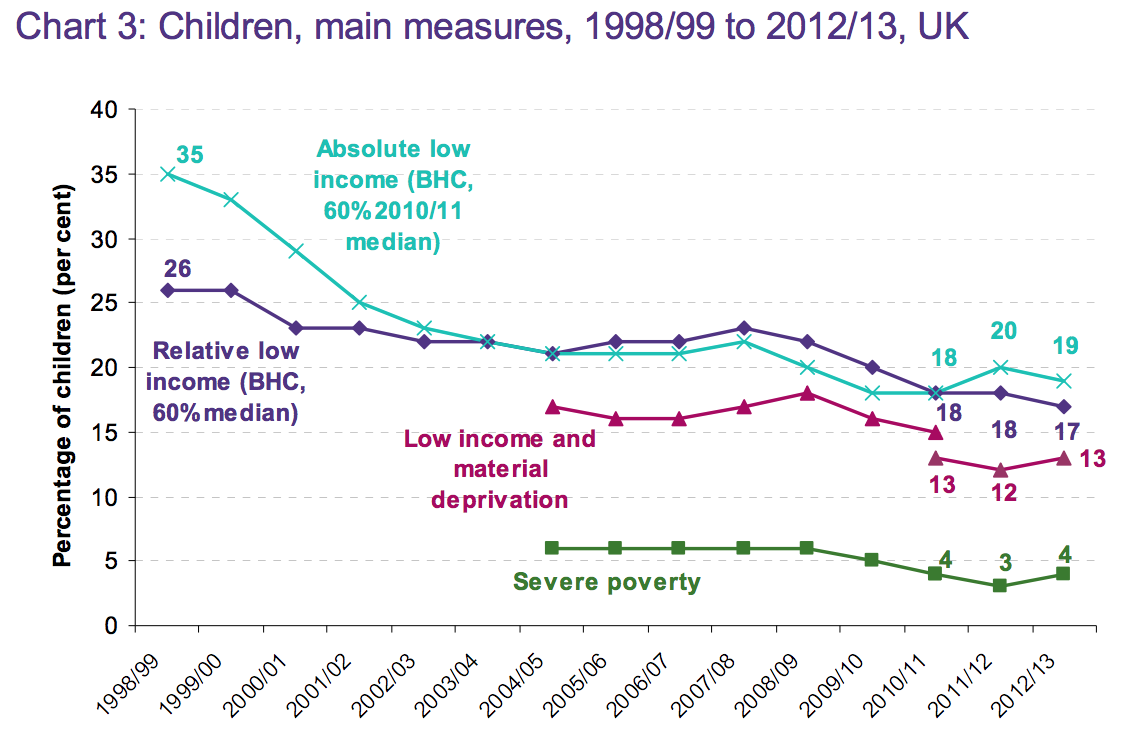

This goal significantly influenced fiscal policy in the U.K. during the 2000s under the Labour governments of Blair and Gordon Brown and even into the new coalition government formed in 2010. The goal is specific — the proportion of children living in households with an income below 60 percent of median household income — and clear. It has fixed timelines, is tracked annually, and is now assessed by an independent Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission.

Did it work? Sort of:

Source:

Households below average income (HBAI): 1994/95 to 2012/13, Department for Work and Pensions

While the half-way goal was missed in 2010 — and the overall one will not be achieved in 2020 — public scrutiny of progress towards such a high-profile goal meant that significant efforts were made. There is not much doubt that, without the child poverty target, inequality in the bottom half of the distribution would have risen faster in the U.K.

The downsides of goals

The U.K. goal also shows that goals need to be set with great care. A relative poverty target hooked to median income has serious shortcomings. First, it is a terrible measure during economic downturns. The best years for poverty reduction were from 2007 onwards: not because poor people did better, but because the recession lowered the median income.

Second, choosing a simple line meant that policy makers tended to focus on giving families near the cut-off enough to get them above it, which had the effect of ‘lifting them out of poverty,’ even though they were just a few pounds better off.

Third, reducing income poverty does not in itself alter the life chances of these children by much. There has therefore been a shift in recent years towards a new set of metrics based on promoted intergenerational mobility (disclaimer: I was heavily involved in this process).

Serious goals can act as real policy commitment devices: out of Afghanistan by 2014, a man on the moon within a decade, and so on. The U.S. has mostly shied away from their use in social policy so far. Perhaps it is time for that to change.

Commentary

Ulysses and child poverty: Goals as policy commitment devices

April 7, 2015